Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In a thought-provoking article, Page 44 Studios (Tony Hawk) designer Lorenzo Wang looks at recent research on happiness, focusing on six key findings that can help us all make better games.

[In a thought-provoking article, Page 44 Studios (Freekstyle) designer Lorenzo Wang looks at recent research on happiness, and the six key findings that can help us all make better games.]

It is our implicit goal, as game designers, to create addictive games that by definition hook our players on pleasure. Games are used as pleasure delivery vehicles. A tremendous amount of research has come out in recent years to address the issue of human happiness, and I think we sometimes need to take a step back from pleasure and address gamer happiness, which is a more "wholesome," long-lasting experience of which pleasure is just a small part.

In this article, I will examine some major findings of recent happiness research, and offer game design approaches that address them. These findings have been appropriated; they were meant to help us understand how and why some people are happier, barring socio-economic factors.

Now, those factors are important, but I'd like to focus on what decisions and expectations that the gaming experience shares with life experience. To do so, it is necessary to define happiness from pleasure.

Happiness comes from the resolution of anger, ennui, fear, frustration, insecurities, and unimportance. Pleasure is an immediate, short-term rush, often visceral, and designers usually to call it "fun." You can have one without the other.

For example, we all know friends who play a certain game constantly while complaining about its every flaw, like my wife when she plays World of Warcraft. She gets no happiness, having played the game to death, alone and guildless. But she gets a visceral pleasure in continuing to kill mobs, farm items, and level new characters.

Quarters were sunk not because I found it fun, but because of the anticipated glory of finishing.

Conversely, playing Dragon's Lair for me was a happy but pleasure-less affair (the play mechanics are merely rote memorization), but the participation in (and completion of) such a challenge, and getting rewarded with a beautiful animated movie satisfied my dedication, even if I hated every unfair death I had to die to get there. The idea of unhappy pleasure versus pleasure-less happiness is a bit extreme, but can be an enlightening distinction.

Finding #1: Happiness is relative.

Reason: Would you rather earn $100,000 while your co-workers earned $200,000, or would you rather earn $50,000 while your co-workers earned $20,000? Most choose the latter. The things that make us happiest in life address secondary emotions, the ones that come after hunger, shelter, and sex. This means that after those primal needs are satisfied, we have no way to classify how happy our circumstances make us except by comparing with others.

It turns out that both lottery winners and prisoners return to their original level of happiness quite soon after their respective life-changing events. Psychologists call this setpoint theory. While the wealthier people in the world are happier overall, the effects of affluence diminish sharply.

It turns out that both lottery winners and prisoners return to their original level of happiness quite soon after their respective life-changing events. Psychologists call this setpoint theory. While the wealthier people in the world are happier overall, the effects of affluence diminish sharply.

Application: There are a few design lessons to take from this. Firstly, keep rewards roughly equal across players, especially in multiplayer games. Fairness, or at least the impression of fairness, is extremely important to generating player trust in the complicit agreement to play that we call a game.

Studies have also shown a strong correlation between trust levels and national prosperity. Particularly in MMORPGs, trust in the fairness of a virtual world is instrumental in the players' willingness to indulge in its fantasy, as well as being productive, well-behaved gamers.

Players will invariably compare their efforts and the resulting rewards with other players. Unfairly treated players will have Robin Hood syndrome, and not respect the game or their peers. They will expect equitable happiness.

Secondly, in single-player components, you should provide a "social" context for a reward, where society means either the player culture, the developer, or the in-game virtual culture. DON'T drop a bucket of gold out of nowhere for any achievement. DO place motivation behind that bucket of gold, show who gives it and why, what sacrifices they made, and how the player earned your quest giver's gratitude.

Also, DO give rewards that reflect and acknowledge player actions. Slaying a hard boss should reward combat prowess, while exploring a secret spot should give a bit of lore or a shortcut. It sounds obvious, but oftentimes reward schedules are so rigid that the progression seems dialed in.

Bad adventure games, for example, are guilty of not being cognizant of a player's accomplishments, rewarding random clicks or combinations of inventory items with unrelated plot continuation. As a puzzle game lover, my first test to see if one is good is to spam random moves, and see how much I score. A good one, like Tetris or Wetrix, can't be won this way.

Although Xbox Live's Achievements aren't a game in themselves, it is fascinating how they are just as addictive as if they were. They provide a meta-game between people that have driven most I know to play in whole new ways. Even when we aren't comparing our Achievement Points with others, we will treat them as a direct challenge from the developers.

Pleasure, though, requires no social context. I can get pleasure from the snapping of puzzle pieces together, the stomping of a goomba, or the realistic sound and animation of my shotgun decapitating aliens in Gears of War. Pleasure is a necessary component to addictive gameplay, but in isolation, it is merely empty calories.

Finding #2: People suck at predicting their future enjoyment.

Reason: Humans have very subjective memories great at recalling essential information quickly, but at the expense of retrieving unreliable details. Studies have shown that a person's feelings greatly influenced by both faultily recalled memories, and also their current state (known as presentism).

For example, people asked about how their overall life happiness was tended to respond positively on days their city had good weather, and negatively on days when the weather was bad. People displace their happiness estimates into their present state.

Applications: Actively predict and meet your players' expectations. The reward you dole out will be interpreted relative to the player's state at the time you hand it out. Giving an amazing reward when they least expect it will blow them away, but giving them pittance after defeating Beelzebub himself is a good way to earn the player's disgust.

Also, try to predict what kind of reward your player expects. Sometimes it's a shiny sword, sometimes it's plot progression, sometimes it's acknowledgment. You don't have to artificially lower expectations to improve your reward, just get them the right reward.

In Zelda: Phantom Hourglass, rewards are justified by making them immediately necessary to progression.

Put your fickle players in the mood to accept what they get. When Metal Gear Solid 3 put a narcoleptic old man with a group of elite assassins, I was astonished, yet somehow thrilled that he outsmarted and killed me. I shared Snake's lesson in humility, realizing the game had anticipated my expectations of an easy fight.

Don't feel you are beholden to your exact promised rewards. You may have told the player exactly what reward they can expect for an accomplishment, but their frame of reference will change when they are standing before your treasure box.

If it was a boring stroll to get to it, then the jewels promised inside can just be cubic zirconia. But if they beheaded a thousand demon bikers to insert the Key of the Gods into the lock, their definition of jewels is going to be very different. Just don't betray their mental image of what their goal accomplishment will look/feel like.

Finding #3: People rationalize their happiness.

Reasons: Studies indicate we hate to regret our decisions, and regret inaction more than poor actions. We are good at rationalizing reasons for the latter to make ourselves feel better. Conversely, we don't like having good things that happen to us explained, as we like the freedom to indulge in all sorts of rationalizations for how we caused some sort of good luck.

Application: While the lesson here seems similar to the last one, exceeding player expectations is slightly more interesting. When I played Mass Effect and chose an "evil" response in a conversation, I was happily surprised when my character didn't just spit out a canned angry line, but threw the poor alien against a wall and held a gun to its head. I felt like I had cleverly chosen a line that perfectly matched my alignment.

Be careful not to abuse this phenomenon. Too much surprise becomes confusion. Most feedback should still be a direct acknowledgment of player skill or dedication, or just as a reaction to input. Designers already know that.

However, when the situation is right, give them positive feedback that allows an open interpretation, such that they can ruminate on whatever vainglorious achievement they did that was responsible. Pick a random player stat like number of bunnies slain, slap it on an [insert weapon] of Bunny-slaying, and give it to the player. They will brag to everyone about what they think they did to deserve it.

Finding #4: People tend to experience loss twice intensely as gain.

Reason: Scientists believe we are biologically primed to have greater loss aversion than a desire for gains. Why do we hold on to losing stocks, telling ourselves it's not a loss until you sell it? There are innumerable theories as to why we have evolved this way, but so strong is this factor that we also tend to expect greater rewards for delayed gratification. Would you rather have $50 now, or $60 next year (forget inflation for a moment)?

Application: Ameliorate and justify punishments. Similar to the presentism finding, people tend to remember their recent experiences more strongly, and that affects their happiness more. Filmmakers discovered that whether or not someone liked the last scene of a film is highly influential in how much they liked the whole film in retrospect. Similarly, the hype surrounding a film quickly causes a so-so movie to become a terrible one when it fails to match expectations.

Two games that handle the design taboo of frequent deaths well are Super Smash Bros. and Resident Evil, where dying is almost as much fun as succeeding because the player is primed for it. In the first, the player becomes part of the hilarious chaos onscreen, and in the second, it fits the survival theme.

It is worse to set-up an exciting situation and not resolve it satisfyingly than to have never set it up in the first place. Imagine being told you won the lottery, but then it turned out it was a mistake! You get an apologetic $100 only to find out the winner was your neighbor. You had a net gain, but you aren't going to be very happy since "losing" the lottery is you present state.

Another tactic to reduce pain is to do what casinos do and surround loss with pleasure. See -- there is a use for pleasure! They surround players with a rewarding environment (comps, drinks, sounds, showgirls, etc.) that acts to positively reinforce financial loss. That's why modern digital slot machines emit clinking sounds despite how gamblers swipe a credit card through now.

Big gory deaths in your typical FPS stimulate the nucleus accumbens, the part of our brain that gives us dopamine-powered orgasms, and it also happens to be activated by the anticipation of pleasure. Stimulating it can prime players into accepting more risk.

Failure in WarioWare is just as fun as winning, more so when you make a fool out of yourself doing it.

But to address player happiness in a game with frequent loss, you'll need to end them on a good note. When players die in your game, use it as an opportunity to praise how long they made that life last, or offer some cool tips, or let them retain some of their items/experience gained.

Make failure funny, dramatic, or informative. Give players a glimpse at an enemy's weakness. Don't just focus on the experience of winning, as they need to always walk away feeling they've made some sustained gain. Then they'll be as happy as they are pleased.

Finding #5: Feeling in control is a significant predictor of happiness.

Reason: Ex-Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan points out that the success of capitalism is almost entirely beholden to one innovation: property rights. When people feel they can trust the system and the reliability of their own actions to safely produce lasting results, they engage life much more positively. The simple word for this is "hope."

Optimism has powerful effects on our mental well-being, and since humans are ordering, rationalizing beings, we need to know that we can safely pursue an objective without being tossed around by capricious and arbitrary consequences. Studies show people are willing to pay a premium for the ability to have more choices, regardless of whether those choices result in better actual gains.

Application: Optimism is so powerful that one study showed it influenced luck. People who classified themselves as unlucky took longer to find a positive message buried in text than those who thought themselves lucky, sometimes missing it completely even when the message was in a huge font! "Lucky" people found it in seconds.

You may think you've built in many player-pleasing features, but if they don't feel it, they won't agree. Take class balance debates in World of Warcraft -- the "cheapness" many players complain about usually has more to do with feeling robbed of control (stun-locks, fears, polymorph) than actual statistical unbalance. Maximize their experience of your design, by making it accessible, not voluminous.

Great game mechanics give us hope, even when we fail. Remember how some games keep you thinking of new strategies and tactics long after you've stopped playing? Emergent gameplay evolves from optimistic problem solving. A couple DON'Ts are called for here...

DON'T take a player's powers away without a good explanation, replacement, or promise of such. DON'T give players inconsistent control schemes. And DON'T let them fail in the same ways despite their best efforts at different approaches. DON'T ever put them in the position of disgusted regret (where they feel an irreversible loss).

We have no excuse not to use this finding obsessively. Not only is it important to happiness, but it is great at generating pleasure. The parkour of Assassin's Creed, the world of GTA that is basically a city-shaped weapons locker, or the omniscient eye we have in The Sims and StarCraft, these are tools for players to act out (or subscribe to) fantasies with. They provide instant positive feedback along with long-term empowerment.

The Roller Coaster Tycoon series made it fun to be in control... of fun!

I want to clarify that giving players control is not the same as making everything predictable. Make it clear to players that something that happens against their will is part of the game, not punishment for playing in an unintended way. Remember that sneaking in something they can rationalize contributes to the feeling of control. Ask constantly what can your player "see" at this point in your game -- do they have (or know where to get) new ideas for play?

A game is a contract between a system (designer) and an agent (gamer) that asks the agent to accept the rules to get at the meat of the experience offered. The agent should be the one playing. When the designer plays the gamer, trust is lost. Therefore, rules should be consistent, and when new ones are introduced, they should nuance (not violate) what the player has learned so far. The same goes for governments.

Finding #6: Happiness is a perspective.

Reason: A recent study explained that the mid-life crisis happens when it does because at that point in life, people have to face giving up their dreams. After and before that happens, people are happiest in life. Before mid-life crisis, people have hope. Why are they happy after giving that up? Because they reach acceptance and appreciation of what they do have.

Application: How can hardcore players pore countless hours into the same game? Could it be that they have come to appreciate the nuances of a game down to the finest details? Watching tournament gamers and competitive athletes, I see similarities in their fervor. Both feel that outside from their in-game triumphs, they have made mostly unique accomplishments that garner admiration and reflect dedication.

And what about casual gamers? Could it be that they enjoy their guild or bridge club as much as the game itself? Don't they love the esteemed history of the New York Times crosswords, or being part of the in-crowd with Simpsons Trivia? Of course, and there are also players that take from both factors as well.

Designers who want happy gamers should see if their work is conducive to appreciation. Super Smash Bros. and the oldie-but-goodie LucasArts adventure games do wonderful jobs of appreciating themselves first, and drawing players in with that enthusiasm. It's great to play something that effuses self-celebration.

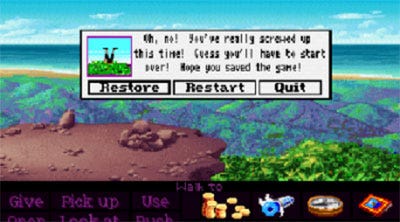

In Monkey Island, I remember walking my character off a cliff in a game where you weren't supposed to be able to die. I sat shocked at the Restart-Or-Quit dialog box that popped up, when all of a sudden my character bounced back from below the screen, landed on solid ground, and said "Rubber tree." I laughed so hard at that smirk through the fourth wall, which not only turned punishment into a gain, but also pulled me into a secret humor only gamers would get.

In Monkey Island, I remember walking my character off a cliff in a game where you weren't supposed to be able to die. I sat shocked at the Restart-Or-Quit dialog box that popped up, when all of a sudden my character bounced back from below the screen, landed on solid ground, and said "Rubber tree." I laughed so hard at that smirk through the fourth wall, which not only turned punishment into a gain, but also pulled me into a secret humor only gamers would get.

Be it the attention to realism in Call of Duty 4, or the genre tongue-in-cheek of Puzzle Quest, we love to see games reciprocate with the audience. Taste is less important than confirmation when it comes to enjoyment. How else can I account for an embarrassing love of the pompous, devil-may-care, adolescent style of the Unreal Tournament series, whose learning CDs and free editing tools trains a proper fanboy out of me?

Researchers found that people predicted their future enjoyment better when they were forced to base their predictions on other people's enjoyment. This also resulted in them actually experiencing more enjoyment, even when they didn't know what they were supposed to enjoy! We already know people suck at predicting their future enjoyment, but see how external (or surrogate) experiences are just as influential as our own opinion?

Therefore, we should train players to enjoy our games, not just trick, cajole, or demand them to. It's hard to quantify this last lesson, but the closest I can come is suggest we show players that a world you create is fun even when players are not there yet. Let them want to join, embrace them when they do.

Never tell them that what they've done in the game doesn't meet the designer's "standards." Never give them rewards or experiences that serve no purpose but as consolation prizes -- even those should gleefully be part of the game. They won't love it if you don't, and if they don't love it, they won't accept it. When they run out of things to accept, they'll reject the game itself.

In Conclusion

From all these findings, we can distill the most important contributors to game-related happiness, which are in no way mutually-exclusive:

Trust (between player and designer/system)

Agency

Acknowledgment

Importance (of player, within "social" context)

Fairness

These are not just generalities of gamer happiness, but of human happiness in general. The only factor completely missing here is physical health, and while I want to say that's really not our problem, hit games like Guitar Hero, Wii Fit, and Dance Dance Revolution made it their problem.

In some ways, game designers should compare themselves to policy makers and relationship counselors. We are in the business of enriching our players' lives. If we do it sustainably, we end up reciprocating, and they will too. We should ask how the pieces of pleasure we prepare for them will fit into their lives.

Unlike pleasure alone, happiness changes the players' perspectives on how they fit into the game's "vision". When happy, player satisfaction can turn into pride, and that translates to word-of-mouth with deeper conviction, stronger fan communities, and a higher worth ($$$) associated with the game. Happy gamers willfully continue to develop your game for you, through culture, community, and loyal play. Pleasure makes for a great release week, but happiness builds great franchises for years to come.

Suggested Reading:

Stumbling on Happiness

by Daniel Gilbert

The Mind of the Market

by Michael Shermer

The Happiness Myth: Why What We Think Is Right Is Wrong

by Jennifer Michael Hecht

Economics and Happiness: Framing the Analysis

edited by Luigino Bruni, Pier Luigi Porta

Happiness: Lessons from a New Science

by Richard Layard

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like