The importance of conversation and player stories in Moon Hunters

"Most heroes' and villains' interpersonal skills are at the core of their identity and legends because they're what drive how we act, and why we act."

"Most heroes' and villains' interpersonal skills are at the core of their identity and legends because they're what drive how we act, and why we act."

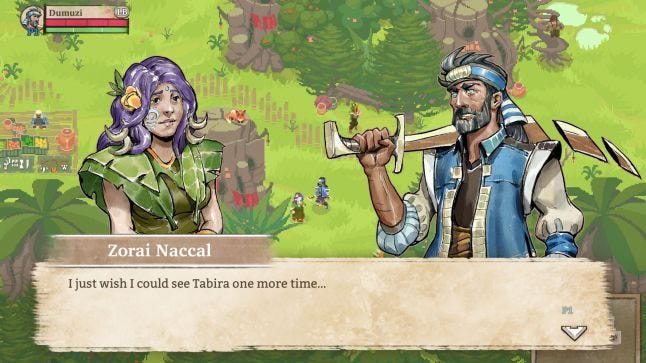

In Moon Hunters, how a player carries themselves in conversation is far more important than their prowess in combat. You can kill dozens of monsters and not see a single change in your character's stats, but a kind or cruel word to someone in town can change your character's strengths and powers. Developer Tanya Short sought to create a game where it was the player's deeds and actions to others, and not their combat abilities, that dictated growth and story development.

"We looked over the various stories of heroes in mythology, there were some that were very violent -- Gilgamesh is a great example of what Moon Hunters would call a Vengeful hero, as he goes around slaying monsters everywhere. So does Beowulf." says Short. "But even these heroes also have other, some would say more important outsized traits that make them remarkable. Gilgamesh begins as very prideful and selfish, and in fact that selfish desire for immortality is what drives most of the action."

In mythological heroes, you often see an importance placed on their combat abilities, but that isn't the most important thing to take away from their character. The same can often be seen in games. While Final Fantasy VII's Cloud is a memorable character to many, it's not because he killed a few thousand wildlife creatures and soldiers. He is memorable for his character arc and the story that was told about him. As players, we remember Cloud's actions, deeds, and words far more than his combat abilities. We recall that he was tough and a good fighter, but more importantly, we remember who he was in the narrative.

This was part of what Short wanted to achieve with Moon Hunters. The character's interactions in the game world are given a great deal of importance, far more than their combat abilities, as this is what players, and readers of fiction, take with them when the game is over. If this is the most important aspect of a game's character, in Short's mind, it should be given far more importance in the play itself.

The importance of story and character development also ties into a more unexplored area of game development. "Compared to the decades-long innovations and iterations in combat design, it's much easier to find your own unexplored space in storytelling design," she says. "I mean, lots of games are telling different kinds of stories in different ways, but I think the human experience of social interaction has a higher number and variance of possible compelling outcomes (and contexts) than the human experience of fights to the death."

To gain stats in Moon Hunters, the player must converse with other characters and help them make decisions, or go through a story event during the camping phase at the end of a given stage. These actions all help move the story forward or allow the player to have a say in their character's personality, both of which provide narrative importance and flesh out the blank slate that is their character. In this, the player's storytelling actions improve the character's combat abilities while also weaving their own narrative.

"The game is primarily about your personality traits, and it only makes sense that those behavior choices would also influence your measurable growth as a hero," says Short. "It's also more satisfying to receive a few Strength points (for example, when you lift a heavy stone), in addition to whatever reputation changes you might get to your personality traits."

Short could have just put the personality traits and decision-making into the game without any connection to the combat and been done with it, but it was important to her that the systems were interconnected with other aspects of the game. If a character's personality could be decided through decisions the player made, then for those decisions to have value, they would need to give the player some appreciable reward for doing so. To get the player invested in their personality, she needed that personality to have some effect on play.

"It seems pointless to write many things that the player has no systemic reason to care about," says Short. "I mean, there's more text in Moon Hunters than, say, Castle Crashers, but the only way I can justify that is if the text has a purpose in being read, beyond satisfying my ego."

This meant making a story system the player would care about, and as such, conversations lead to improved stats in combat. A player might feel inclined to hammer their way through the dialogue, but conversations with other characters often involved a choice of some sort, with both decisions offering varied stat boosts when chosen. This wasn't something as simple as a 'good' or 'bad' decision, but rather one where players had a good reason to make a choice (to get the stat boost) without thinking about whether they were making the right call to get the right boost.

"Outside of the central camping character-building scenes, conversations often don't signify which choice will give you Strength and which will give you Faith etc -- which naturally emphasizes the softer, more human side of the choice." says Short. "When you choose to Attack someone versus Listen to them, the clearest and most intuitive difference is that one seems Vengeful and the other Patient, or maybe Wise. The fact that the former may result in physical gains (or damage) and the latter might result in more mental gains (or crises) is secondary to the interpersonal consequences."

The player may be able to guess what action will give them which boost, but the game doesn't often try to make that clear. Instead, it leaves the decision, as well as some of its moral, intangible consequences, vague, letting the player guide their own story without letting a need for certain stats infringe on the storytelling. It doesn't eliminate it altogether, but it does encourage a player to just tell their own story and let combat stats fall where they may.

Despite the importance placed on the story of Moon Hunters, Short never considered removing combat from it entirely. Why?

"There are a few reasons,"says Short. "The biggest one is pacing. Moon Hunters is based on a prototype my partner and I made five years ago called Dungeons of Fayte, and what we learned from that is the importance of relief, between the relative drag of reading text after text after text. When it's well-written, dialogue is lovely, and I'm happy to read plenty of interactive fiction."

"However, I can get antsy, especially when I'm playing with friends. Punctuating text-heavy villages with hectic 'adventure' zones is the classic heartbeat of RPGs, from Dungeons and Dragons to Final Fantasy, and it's even more important when friends sit beside you on the couch."

Players enjoy a good story, but sometimes, it's the spaces between that matter. Even when reading a story, action and exposition will shift back and forth, the pacing helping to keep the reader engaged with the plot through variety. The combat and story feed off each other in this regard, with the story providing combat boosts, the action providing a break from too much story, and then the action needing the player to advance their story as a break from combat.

From a purely marketing perspective, combat is also an appealing thing to add to your game. "Action combat makes it easy to communicate why the game is fun, for people who haven't played it yet. Even if it's expensive to develop, combat systems are immediately visually understood by even the most casual glance during a trailer. People can watch our trailer and immediately understand what the core of the game is, and whether or not they might like it... which is less easily achieved with system-heavy gameplay." says Short.

Part of letting the player tell their own story meant letting them guide themselves across the procedurally-generated world. Not only was this an area of Short's expertise, but it also lets the player create their own tales as they explored different lands across each playthrough.

"The 'ragged' approach to lore and setting occasionally means that it's quite obtuse - some players complain that it's not clear where to go, or what to do, or what the point of anything is, but personally that's something I love in games - when I can feel my way through and enjoy the moment. It's our hope that players can see a pattern in their actions, and that the game can reflect that in some way."

The elements may seem loose in the narrative, but that is because Short wants the player to tie them together themselves, to an extent. Locations and places are put together randomly by the procedural generation, which can make for some difficulties in storytelling outside of the player's own mind. By using the player's creativity, which is already being channeled through moral decisions, they can join in weaving a more interesting story for their player. Their gameplay experience is uniquely their own, and therefore their story is as well.

Even so, there is an in-game story that comes together through the player's actions. To wrap up the personal narrative each character builds with their actions during a playthrough of Moon Hunters, the players are given a short folk tale about their character when the game concludes, either through failing to defeat the game's Sun Cult or beating them. Win or lose, the player has still written a story.

"There are three major elements to each myth: the 'Outcome' (whether the Sun Cult triumphed or didn't, and how that effected the player based on their stats), the 'Constellation' (what archetype we map the player's traits onto), and the 'Deeds', which describes (sometimes with exaggeration, as legends do) a few things that the player did/accomplished during that play-through." says Short.

This discourages a need to win or lose, and focuses the game more on telling a story. Some of the most famous stories of historical figures involve failure, and so Moon Hunters also includes loss in the folk legends it forges about its characters. The player's story remains their tale whether they win or not, and so the game collects the interesting things they did along the way, whispering the story by imagined campfires.

By tying character decisions into combat stats, Moon Hunters gives story an importance to the action. It makes the character's personality tie into all aspects of play, giving the player a reason to care about what kind of person their character is. This flows through the rest of the game as it pens a folk story about the player's deeds in combat and by their words. In doing so, Moon Hunters becomes an action game with a focus on who the player is, and what kind of person they are, honing in on the narrative while still giving players action and adventure.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)