The Era Of Behaving Playfully

How can incorporating real-world behavior change the fundamental play of games? The developers behind games that delve into this question, such as The Sims 3, SpyParty, and Facade, answer this question.

[How can incorporating real-world behavior change the fundamental play of games? The developers behind games that delve into this question, such as The Sims 3, SpyParty, and Facade, answer this question.]

Playing is behaving. From childhood experimentation and role-play to the competitive simulations of adults, it's impossible to separate even the most abstract forms of play from human expression. Yet video game design is dominated by the perceived need for win conditions.

If an interaction can't be parsed into passing or failing it can't be counted as fun. Without the threat of failure there is no fun. Yet, it's not victory that drives the invented play of kids on a playground, nor friends laughing over an inside joke.

Video games built around behavior aren't often given the same attention more competitively oriented games are, but they're no less important a part of the industry.

Games like The Sims 3, Heavy Rain, Nintendogs, Façade, Animal Crossing, and Harvest Moon are all made for the pleasures of expression. These are games played for their creative experiences more than their victory conditions.

Recent years have seen a wall built up to separate hardcore and casual games. It's an arbitrary distinction used to diminish games a person doesn't like by shoving them into a category defined by non-seriousness. A truer way of looking at video games is on a spectrum defined on one end by competitive games and on the other by purely expressive ones.

There are many subtle shades in between -- Mass Effect's conversation system, Call of Duty 4's nuke sequence, Spore's creature creator, Nintendogs' loyal competitions. Indeed, as with earlier media, the most impressive works often blur distinctions between genre and find ways to join seemingly opposite ideas.

There has been much inquiry into objective design, competitive incentive, and metering the rate of achievement, yet thinking about non-competitive ways of creating expression is a blindspot for many in the video game industry. What follows, then, is a survey of how and why expressive behavior can be used in game design, both as a means to a competitive end and a playful end unto itself.

A Sweeping Surprise

"When you're making the base game, you're trying to capture the essence of everyday life in a way that will appeal to nearly everyone," Charles London, creative director of EA's The Sims Studio, told me.

"Basic things, like sleeping, eating, being romantic, or watching TV, are very high on the list; without those, there's really no core to 'everyday life' around which to wrap more exotic content."

The Sims series is the alpha and omega of non-competitive games. You can't beat a Sims game, but you can spend hundreds of hours experimenting with its web of interrelated behaviors. The reward for playing comes from small surprises and moments of simpatico rather than increasing difficulty curves.

"We rarely design activities or interactions for our Sims without having an overarching theme, like seasonal winter snow play, or going out to nightclubs and restaurants, or learning to be a firefighter," London said.

"Once we've identified the activities that are core to making the theme believable, the constituent behaviors come into pretty sharp relief. The idea is to make them as modular as possible, so that the player has as many chances to be surprised by what happens as we can give them."

The Sims' use of indirect control is crucial to its mix of familiar action and unexpected results. It allows the player to plan sequential events instead of focusing on repetitive action. Because the player can't immediately affect the action they are also more vulnerable to surprise; they become implicated spectators instead of direct actors.

"We have a tradition of breaking up interactions by subject matter and by object," London said. "In the core game cycle, you are using the money your Sims made to purchase new objects that improve their lives. This means it's really at the object level that you are giving commands. Having a 'Clean the house' button really doesn't bring home the feeling that there's a new object for your Sim to use, such as the TV."

"That said, some objects have a higher granularity of control than others. You want to feel like you are telling a Sim to do a specific thing, but not so minutely that you are the Sim. For example, you tell a Sim to prepare breakfast by choosing waffles. But you don't actually control their whisking the batter. Neither do you say 'Eat', as that robs the player of the specifics of storytelling, the center of our game. It's a granularity that we're been refining on a case-by-case basis since we started this business."

Emotional Intelligence

One of the most elusive goals in game design -- or really in any art form -- is capturing the emotional significance of an action. With the thrill of winning removed, behavior games must have satisfying emotional feedback in their systems to keep players involved.

"My focus has really been on AI as a form of expression," Michael Mateas told me. Mateas is a professor at University of California Santa Cruz's Center for Games and Playable Media and one half of the design team that made Façade, the 2006 conversation game about an awkward dinner with a couple on the verge of breaking up.

"I like to think in terms of playable models," Mateas continued. "A simulation is a model of something -- a model of the world. But a computational model isn't necessarily playable. What makes a model playable is that it presents a player a continuing series of actionable decisions."

"Those actionable decisions can be built into challenges for the player and the simulation provides continuous and juicy feedback on the state of the underlying model and how your actions affect it."

In the world of pass/fail design this concept leads to the problem of better AI not necessarily being more satisfying to play against. This is often posed as a challenge to AI development, but it's more of an issue with objective design. If playing a shooter with realistic and defensively-minded AI can be frustrating it's just as much a result of there being nothing meaningful to do besides shooting.

"I really think AI is the future of creating new kinds of playable models because it can make aspects of games that currently aren't playable playable," Mateas continued.

"Going back to the old storytelling in games conundrum -- the reason that exists is because the story aspect of most games isn't playable, and the reason it's not playable is because there's no underlying playable model of the story itself. It's not able to present the player with a continuous sequence of actionable and interesting choices."

For Façade, Mateas and design partner Andrew Stern (lately of Ngmoco developer Stumptown Game Machine) created a conversational AI that would be able to respond to any line a player might type in. It was imperfect in a way that pass/fail oriented players could instantly exploit, but it also struck a loud note of excitement among people interested in non-competitive play.

In the same way that Call of Duty games only work when you're moving forward and trying to complete the objectives, Façade worked surprisingly well when you acclimated to its limitations and learned to play within them.

The Prom

Mateas's newest game is called The Prom, a combination of Sims-style planning with the interpersonal melodrama of Façade. The Prom, targeting a March release on Facebook, is about the social machinations in a high school during the two weeks leading up to prom. Players can speak with other characters and try to encourage attraction and budding relationships between different characters and cliques.

"It's almost like social physics," Mateas told me. "In the same way that physics puzzle games don't script a precise solution to a physics puzzle -- the physics engine makes available a number of emergent solutions. This is trying to do that for social interaction with its social physics engine."

One of the keys to this system is the idea of character affinities to underscore interactions. Mateas here refers to Façade and Grace's secret desire to be an artist. He and Stern came up with this story thread in writing her back story and it became a way of communicating a side of her interior self. That idea has mushroomed in The Prom. Mateas is building the AI in The Prom to be cognizant of a whole network of interior affinities that all the players will have.

"Social games themselves are part of the AI," Mateas described. "It knows what an affinity game is. It knows what a flirt game is. It knows what these various kinds of social interactions that are designed to change social states are and we've got thirty of forty of them in The Prom."

"The system's able to figure out dynamically given how the characters are becoming enmeshed in that social game according to their back stories and what kinds of stories to bring up and so on. That makes the space way more generative than it was in Façade."

Feel This All Together

Just because a game focuses on behavior and emotional play doesn't mean it must always be open-ended and AI-centric. Jeroen Stout's Dinner Date is a directed experience about the myriad anxieties a man can go through waiting for a date to arrive. The game is in first person and players are told they control the main character's subconscious at the outset.

As players sit in the cramped apartment kitchen while dinner grows cold they can trigger scripted interactions with different objects at the table and around the kitchen. Underscoring every action is the self-effacing monologue of the nervous man tottering on the edge of being stood up.

"The game started as a project I did at the University of Portsmouth," Stout told me. "It was a little bit of a rebellious joke at first -- thinking about a game with just one man sitting at a table because it was very much subversion of the abnormal power you have in most games.

"The idea became that by doing his actions you would focus on his story a lot more. So I started writing from that perspective -- Julian has multiple layers, from his immediate problem of being stood up to bigger problems that he should actually focus on. As a player, hearing his thoughts, you get an insight in him which he himself lacks."

Where other behavior games use variations on indirect control and planning there is purposelessness in Dinner Party's available actions. The hopeful object of the game is to have the date finally arrive, but there is nothing the player can do to affect this outcome. In turn, each available interaction is an echo of the futility of the situation, having one's hopes hanging in the gap between romantic possibility and rejection.

"I think the original concept right from the start did not include any narrative significance in the actions," Stout said. "It was predominantly 'what actions are there for a person sitting down at his table' and a thought that came from acting -- that by playing out these actions you get closer to the person."

Even with direct control Stout had to choose how interactive to make each action. Would each sip of wine be a gestural movement with the mouse? Would the smearing of a spread on the bread be a series of swipes?

"I realized I could not translate mouse actions to Julian's actions; Julian has a certain way of moving," Stout said. "Leaving the player free to control the hands would also introduce the 'crate problem', where a player, seeing something he can meddle with, cannot stop himself from picking up, say, a crate and throwing it around. If the player could swipe everything off the table the game could not function and placing arbitrary restrictions on free movement sounded like a big maze of invisible walls.

"So I settled on doing binary actions, which would be interesting enough to be chosen, but also make the interface a little bit organic by making the bubbles float a little and almost fight for attention."

The resulting interface has the mouse controlling Julian's view while icons hover above objects in the kitchen. These actions play out as discrete scripted moments whose order is chosen by players.

"I did create a basic set of actions that seemed plausible to me; looking at the clock and tapping the table," Stout continued. "I selected them by being as natural as possible, but also to change his posture; tapping the table, looking at the clock, hopefully to increase a sense of embodiment.

"In some way it was strangely easy - once I realized I could make a person tap a table I could make him look at a candle. Before I started I would not have considered those actions, but forcing the actions to remain things you subconsciously do in a way increased what I could do."

Strike a Poser

Chris Hecker's SpyParty is an amalgam of expressive and competitive play. Instead of just trying to create more realistic AI, Hecker's game asks players to adapt their behavior to what the AI is doing or else risk failure. The game is designed for two players, a spy at a cocktail party with a specific objective (e.g. plant a bug on an ambassador) and a sniper observing the party and trying to pick out the real human player from the other AI ones. It's a kind of reverse-Turing test.

SpyParty grew out of the Indie Game Jam -- supported by a loan of assets from The Sims, coincidentally -- a game creation event focused on a particular challenge each year, like making a game with 100,000 characters in it. This started a line of thought in Hecker that would eventually become SpyParty, though he insists there wasn't a simple and linear path from original idea to working prototype.

"If you're trying to do something interesting, new, novel, innovative and unique you don't start with ideas," Hecker told me. "I mean obviously you start with an idea, but you don't have an 'idea' phase and then a 'typing the code' phase.

"The missions in SpyParty are basically spy and mystery film tropes. One of them was clearly going to have to be poisoning somebody's drink. That's an interesting social dynamic: a person drops dead in the middle of a party, people rush over to help them, they carry the body out, there are drinks in the world, you offer a drink to somebody.

"So I was trying to get a first version of this mission done for PAX, which was in September. It was pretty clear I wouldn't be able to get the mission done for PAX so I just decided to try and get drinks in the world and then write the mission later."

As Hecker worked on the challenges of animating for drinks, determining a probability for who would and wouldn't have drinks from the start of a mission, and how many sips it would take to finish a drink, he realized there was a layer of gameplay emerged from the simple act of drinking. Drinks added a special tension because if you are holding a drink there are certain objectives that you cannot perform until you finish your drink and set it down. Suddenly a mundane action became a dramatic one with competitive context.

"If you see as the sniper someone slamming a drink at the beginning of the party that's a piece of evidence that that person might be suspicious," Hecker said. "The partygoers don't actually need to get rid of their drinks, they're not trying to get rid of them so they can do their missions."

"Likewise, it behooves you to take a drink from the waiter after you've finished the missions you can't do with a drink in your hand, because now anyone with a drink is less suspect.

"There's gameplay lying all over the floor in these human interactions. Not even getting the mission in, but just having drinks in the world, makes for interesting gameplay at the human behavioral scale."

Underpinning all of these gameplay possibilities is Hecker's choice to make SpyParty a competitive experience much closer to the pass/fail construct than many other behavior games. Hecker sometimes describes the game as The Sims crossed with Counter-Strike (a game he described as one of his favorites). SpyParty is not about expressive joy but expressive tension.

"In some senses you're frustrated when there's too much flourish [in SpyParty]," Hecker said. "Right now pulling the microfilm from the book [a spy objective in another mission] used to be really subtle but the sniper could almost never see it. I had to give it more flourish. In some sense you're a dumb spy because of that, you look over shoulder and then do this thing and shove it in your pocket. But I had to make it that bold because the sniper would have never had a chance."

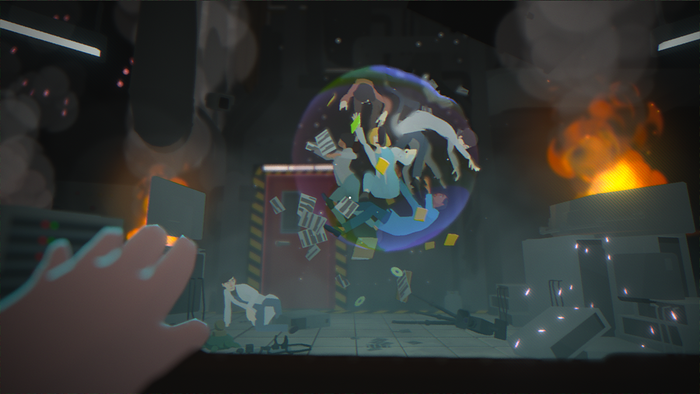

SpyParty

This is nearly opposite to what a game like The Sims or Nintendogs, where a lavish animation is a visual reward. In SpyParty detailed animations are almost a form of punishment, a great competitive weakness that requires some significant tactical planning to compensate for. When the game is at its most visually rewarding, it's also at its riskiest.

Ms. Game Developer, Tear Down That Wall

What's the difference between Borderlands and Cow Clicker? Or Heavy Rain and Sally's Salon? The distinction between hardcore and casual -- a widely unchallenged standard -- can't tell us anything about these games or the people who play them. For too long journalists, developers, and enthusiasts have supported this hollow distinction as a kind of last gasp against the influx of heretics from the outlands -- the stereotypical soccer moms, granny gamers, and tweens ignorant of the poetry in StarCraft's build orders and Counter-Strike's sight lines.

A more honest and coherent way of thinking about the video game industry is along a spectrum, defined at one extreme by pure competition and by pure expression at the other. In this way, The Sims can both be a casual diversion and a hardcore, 200-hour obsession. The most interesting challenges in the coming years will have nothing to do with reconciling the indefinable non-entities of hardcore and casual, but instead learning how to join purely emotion-driven play with pass/fail gaming.

The early decades of the video game were necessarily rule-focused in the same way that cinema's first decades were fixated on plot, peaking in the iterative studio days of the 1930s and 40s. Those hard and fast genres gave way to accommodate a new wave of creators who joined pure expressionism with linear narrative to create the standards of cinematic pacing and symbolism that are still with us today.

In the same way, rule sets are slowly beginning to accommodate emotional expressionism, with many of the most interesting games finding ways to meld these seeming opposites.

The real challenge facing game designers now -- just as it faced filmmakers, writers, painters, and actors -- is how to make action emotional. The future is not in building up the wall that separates FarmVille from StarCraft II, but in tearing it down. We're moving into an era of behavior and expressivity, of playing to feel instead of playing to win. Those who've embraced the challenges of designing playful behavior are already further down that road, one that many still won't even acknowledge.

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like