Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

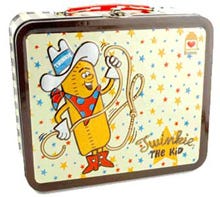

Hostess might be bankrupt, but the denial of Twinkies continues! In the 13th annual installment of The Designer's Notebook's popular column, Ernest Adams tackles more reader-submitted design decisions that mystify and dissatisfy players.

Unlucky 13! Since the demise of Hostess Brands, the exclusive worldwide suppliers of Twinkies to game designers, this may be the last Bad Game Designer, No Twinkie! column. The company is being liquidated and its assets sold off. However, the Twinkie may live on in another guise. Rumor has it that Walmart is considering buying some of the Hostess properties, which would make perfect sense: a low-grade snack food for sale at a company that provides a low-grade shopping experience.

Of course, if Walmart does take over the brand, the product may not be quite the same. As Electronic Arts knows, you can stick a much-loved name onto a box containing something completely different, as they did with Syndicate. It's not a good idea, though, because fans of the original will trash you on the internet. Take note, Walmart: you can't turn a tactical Twinkie into an FPS Twinkie without paying a price.

For the moment, however, there are still plenty of Twinkie Denial Conditions to discuss in my annual compendium of gamer-contributed goofs and gaffes. Here are this year's ten:

Many early video games generated their challenges (and associated game worlds, if any) randomly. In these days of finely tuned level designs costing millions of dollars to build and script, we're not that used to thinking about randomly generated challenges, but they're still very much around in casual games.

Randomly generated challenges offer endless replayability, but they have to be constrained by some kind of heuristic to make sure they're good. By "bad," I mean impossible, overly easy, or just plain boring challenges that the game has generated randomly.

Mary Ellen Foley pointed out that Yahoo Word Racer, a Boggle-like multiplayer game about finding words in a random matrix of letters, sometimes produces a layout containing no vowels at all in the first round. The players have to sit around and wait for the two-minute timer to run out before they can go on to the next round. This is ridiculous. The game contains a dictionary to check the validity of each word the players enter; surely it could check to see that a given layout includes a minimum number of words before sending it to the players... or at least a few vowels.

She suggested that an "I'm finished" button would let the players jump on ahead without waiting for the timer to run out, once they all have pressed it. That's a good idea for any multiplayer, simultaneous-turn based game, and a suitable workaround for Word Racer's problem. But they should fix their generation algorithm too.

Ian Schreiber writes, "A few free-to-play games recently seems to hide all of the best content behind a paywall. Now, obviously I'd expect SOME good content to be pay-only, but I'd also expect some of it to be revealed to give the players incentive to actually buy. Otherwise you're presenting the mediocre parts of the game to your customers and asking them to take it on faith that it gets better if they pay (instead of the more likely result, they see a mediocre game and assume that's what you're selling).

Ian Schreiber writes, "A few free-to-play games recently seems to hide all of the best content behind a paywall. Now, obviously I'd expect SOME good content to be pay-only, but I'd also expect some of it to be revealed to give the players incentive to actually buy. Otherwise you're presenting the mediocre parts of the game to your customers and asking them to take it on faith that it gets better if they pay (instead of the more likely result, they see a mediocre game and assume that's what you're selling).

"It's like a game designer searching for a job, and removing the best parts of their portfolio to use during the interview. Then they wonder why they never get an interview. I see this as a particularly nasty sin of game design because it doesn't just ruin the game, it ruins the company's entire business model."

I'm going to have to set up a new section of the No Twinkie Database to cover this one. Most of my Twinkie Denial Conditions are issues that hurt the player's experience, but this is one that hurts the game company. Still, a design flaw is a design flaw. Ian said that he couldn't name names, unfortunately, but that he had seen three iOS games in a row with this problem.

These are similar to, but not exactly the same as, uninterruptible cutscenes. Tyler Moore writes that some games "force you to watch the same animations or script for mundane actions with a predictable outcome, blocking gameplay or interaction until the animation is complete. This does not apply to animations that have a variable reward at the end (as in Zelda, opening a chest), only to those with a certain outcome." His examples were watching the skinning animation over and over to collect a resource in Red Dead Redemption, and being forced to listen to the same tired shopkeeper greeting when you want to sell your wares in Skyrim.

This one is so obvious I can't believe I didn't mention it years ago. Someone named Jan wrote to say that in Max Payne 3, Max in the cutscenes (which are numerous) is very different from Max as the player plays him. Having fought huge numbers of armed men successfully before, the player arrives at a critical confrontation only to have control taken away from him. Instead of the battle he was expecting, he is shown a cutscene in which he fails to do something that he could handle easily in gameplay.

Certain kinds of interactive stories have a tendency to seize control of the avatar in order to insert narrative plot material, leaving the player wondering who's role-playing this character anyway, him or the game? It's okay to introduce plot twists and unexpected developments in the game world at these moments. It's not fair -- and very frustrating -- to make the avatar perform below the player's own competence level or do something blatantly stupid. Valve's games, notably, don't do this.

There's a place for cutscenes and scripted sequences, and in story-heavy games with strongly characterized avatars (such as adventure games) it's reasonable for the avatar to have a mind of his own at times. But whatever the avatar does outside the player's control, it had better be similar to the things he does under the player's control. Games are not movies, and when you give the player a role to play, the player, not the designer, is the actor.

We're all annoyed by TV commercials that are far louder than the content they're sponsoring. (These are now illegal in the United States.) Games can do it too, and not only with sound.

Colin Williamson writes, "The game in question is Assassin's Creed III, a very dark game which signals every gameplay transition or cutscene start with a smash cut to an all-white screen. If you're playing in a dark room or, even worse, on a projector, this is the equivalent to a full assault on your retinas."

This is the reason the fade-in and fade-out were invented for film decades ago -- in a darkened cinema, a sudden cut to an all-white screen is abusive. In audio production there's a technique called dynamic range compression (nothing to do with data compression) in which the equipment amplifies quiet sounds and reduces loud ones to keep the dynamic range within comfortable limits so that the listener doesn't have to adjust his volume control all the time. This doesn't prevent him from cranking his speakers, but it does avoid violent shocks.

Tess Snider says all that needs to be said:

When was the last time you were walking down the street, and some complete stranger randomly paused next to you, and started telling you why he came to the city, who his rival was, or how his business is going? If it did happen, wouldn't you think he was crazy? In Skyrim, almost all NPCs do this. It's so weird and annoying that people have made mods to make it go away.

Skyrim isn't the only offender on this count, though. Throughout RPG-dom we see weirdly trusting NPCs who insist on telling us all sorts of personal information that we really don't need to know and which no normal person would ever share with a complete stranger. No wonder bandits robbed them blind.

Tess thinks this has to do with frustrated writers who are bored writing variations on "howdy" for NPC greetings and want to express themselves a bit more. I think it may be borrowed from TV cop shows, in which a lot of exposition has to be crammed into a limited amount of time, resulting in witnesses who provide far too much information:

Cop: "Did you hear any unusual noises at about 10 last night?"

Witness: "No... I sleep in the back of the house. My husband and I started sleeping in separate bedrooms after our third child was born. Things really haven't been the same between us since."

Whatever the reason, don't do it. Read your dialog aloud to see if it sounds like actual conversation. Really chatty people do exist, but they're rare.

So many people have sent in variations on this complaint that I can't credit them all. An invisible wall is a barrier in a 3D space that prevents the player from entering a zone that the visible environment, and all the rest of the game's mechanics, tell him he should be able to enter. (I've already discussed a related problem, having to stand on, or jump from, a tiny precise location in a 3D space.)

One of many, many examples is the waist-high barbed wire fence around the Chernobyl exclusion zone in S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl. Invisible walls are conceptually similar to, but implemented differently from, the wooden doors that you can open with a key but can't break down in an RPG. They're a failure to implement a visually credible reason for the player's inability to go someplace that he ought to be able to go.

Let's use some common sense here, people. Unless the avatar is in a wheelchair, a low fence is not an obstacle. If the avatar is supposed to be a commando or a superhero, a six-foot fence isn't one either. Nor is a pane of glass. It's also unfair to construct a visually enticing area beyond an invisible wall. If you signal that an area is worth exploring, then it needs to be explorable. Keep the areas inside the boundaries of your world more interesting than the ones outside.

Players of video games work toward goals the game sets for them, some of which produce rewards of varying value. These can even be negative. In an RPG, you'll occasionally pick up a cursed item that does more harm than good. You can usually check it first, though, or get it fixed, or drop it. On the other hand, something that you buy in a game shop with in-game reward money -- equipment upgrades, for example -- really shouldn't do you damage. A correspondent named Cyrad writes of the popular action RPG The World Ends With You:

Equipment comes in the form of clothing you purchase from stores. In addition to stat bonuses, each article of clothing also grants a passive ability that is unlocked/activated when you establish a good relationship with the store clerk. These abilities were usually things like "your attacks randomly debuff enemies' strength" or grant you a defense boost when heavily injured.

After spending most of the game unable to find shoes with decent stats, I finally found a pair that I absolutely loved and spent a fortune buying a pair for each party member. The clerk later revealed the shoes' ability, which granted a minor perk at the cost of making every enemy attack knock me off my feet.

Getting repeatedly hit-stunned while attempting to heal is the most common way in the game to die, and by this point, most enemies spam unavoidable projectiles. The unlocked ability essentially made this item suicide to wear. The ability cannot be toggled or removed. The shoes cannot be sold. Any new duplicate I buy will also have the ability.

You punished your player for buying an upgrade, Square Enix? Bad game designer! No Twinkie!

The example for this one is an oldie, but the principle applies regardless. Deunen Berkely wrote, "Thou shalt not repeat multiple missions in the same cave/building/area over and over. You see this most blatantly in Star Wars Galaxies MMO, but other games fall to the temptation as well... you are trotting through the cave and see NPCs or items that don't react to your mission, or worse, you have to kill everybody to get to the bottom.

You fight your way back out, only to get another mission just a few activities later that sends you back into the same darn cave, kill everybody again, reach different things around said cave/building/area, and then fight your way back out again. By the fifth time, it's really dull. Puts the grind in grinding, you know?"

We can use a location for several missions if it's big and diverse enough, as in the Grand Theft Auto games. But you shouldn't do this too much with a location that the player explores completely in the course of a single mission.

This is a corollary to an earlier TDC, Bad Guys With Vanishing Weapons. You spend a lot of time clobbering a serious bad guy with a big weapon and what you actually find on his body is a pointy stick.

This is a corollary to an earlier TDC, Bad Guys With Vanishing Weapons. You spend a lot of time clobbering a serious bad guy with a big weapon and what you actually find on his body is a pointy stick.

In this case, Sean Hagans writes, "Entire nations run from the character's name and the only thing standing between him and the total fulfillment of his overlord's plans (usually imminent world domination) is your party of heroes... You SOMEHOW are able to barely make it out of the battle with your lives.

Due to your soundly punishing argument, the villain has a change of heart and joins you (OMG! I get to use HIM! YES!!!). Much to your despair, the villain is seen to be named 'Bob the Boy Wonder' and can only perform a basic slash attack with his slightly over-sized blade of dull wood."

Not fair. Now a fair (and very funny) example occurred when the Avatar from the Ultima games showed up in the very last level of Dungeon Keeper. He was the ultimate enemy, but he could be converted with enough work -- and when he was, you got to use every bit of his awesome power.

Recently Lars Doucet told me that his company, Level Up Labs, does a "Twinkie pass" over their designs. They check each game's design against the No Twinkie Database to see make sure they haven't included any Twinkie Denial Conditions. It's nice to know these columns are having a real effect. Send your own complaint (check the database first to see if I've already covered it) to [email protected].

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like