Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

We're all familiar with the warfare between the Israelis and the Palestinians, but can a game teach us about peacefare? Ernest Adams explores this from a designer's perspective using Impact Games' upcoming PeaceMaker.

As I write this, Monday the 29th of January, violence between the Fatah and Hamas factions in Palestine is tearing the guts out of Gaza City. Dozens have been killed in the last couple of days; shops and government buildings set ablaze; and fighters from both groups have begun a wave of kidnappings, snatching senior leaders from the opposition and holding them for ransom.

The Palestinian economy, already depressed, weakens further as businesses close and people stay home to avoid the danger. The chances of forming a functioning government in Palestine are at their lowest ebb. Negotiations with Israel are at a standstill, because how can the Israelis bargain meaningfully with someone who might be dead or kidnapped tomorrow?

Personally, I’m so fed up with these militants that I’ve ordered a targeted assassination of some of their leaders. The last time I tried this, it fizzled. My death squad broke into the man’s home and found nobody there but an old lady and a little girl, so they left. Word got out and everybody snickered at the incompetence of my security forces. This time, however, things went better: they blew him up with a car bomb, and I’ve seen a photograph of the blazing car. The militants are furious, but my standing with ordinary Palestinians has gone up a little, and that’s my main concern. The rest of the world, for the most part, doesn’t much care about the political murder I’ve just committed.

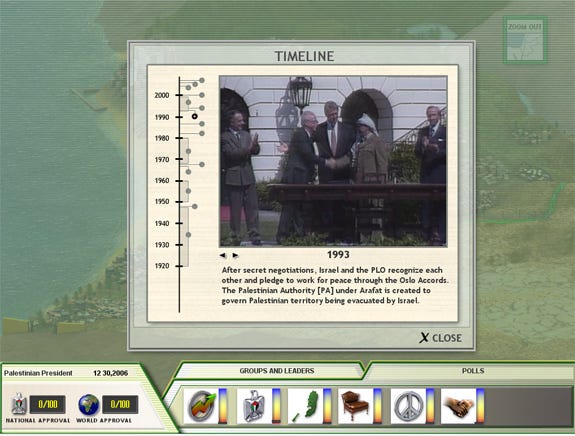

The first two paragraphs of this column are actual fact, and refer to the browser window on the left side of my screen, which is open to the BBC News website. The third paragraph refers to the right-hand window, in which I’m role-playing the President of the Palestinian Authority in a pre-release version of PeaceMaker, a forthcoming title from Impact Games. The contents of the two windows are startlingly similar, and the effect is greatly heightened by the game’s use of real news photographs and video footage from Israel and Palestine.

There’s no animation in PeaceMaker, nothing cute, nothing that someone can dismiss as “only a game.” When a missile strike goes awry, or a suicide bomber strikes, the blood and bodies you see on the screen are those of real people. More than any other game I’ve ever played, PeaceMaker portrays the truth – or a subset of it – both the good and the bad.

The game styles itself “a video game to promote peace.” It began life as a master’s degree project at Carnegie-Mellon University’s Entertainment Technology Center, but is now a commercial product due for release in a few weeks. PeaceMaker has already received a great deal of attention from the world press. You can read other reports through an extensive collection of links available at the game’s website.

As you might expect, I’m chiefly interested in it from the designer’s perspective. We’re all familiar with the concept of asymmetric warfare these days, and almost all war games are asymmetric anyway. But what about asymmetric peacefare? The folks at Impact Games kindly let me take an early look.

You can play as either the Israeli Prime Minister or the President of the Palestinian Authority. The goal – for both sides – is to establish a successful two-state solution to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, and thereby win the Nobel Peace Prize. In effect, this means ending the pervasive chaos in Palestine and making it prosperous, peaceful, and self-governing.

Interestingly, this is as much Israel’s goal as Palestine’s. As the Israeli PM, you actually spend a lot of your time thinking about the living conditions of the Palestinians. The game may not be terribly popular with Israeli hawks; but then it won’t be popular with Palestinian hawks either, as peaceful coexistence is the only way to win.

The game is carefully non-partisan, but still highly asymmetric, – your options are quite different depending on which side you play. In both cases, victory is defined as maximizing your political standing with two groups of people, but they aren’t the same groups. The Israeli Prime Minister has to win the trust of the Israeli people and the Palestinians too. The Palestinian Authority President has to win the trust of his own citizens, and also, rather than the Israelis, the world community. (I don’t know why the designers made that part asymmetric. Perhaps they felt that no Palestinian leader could ever win the trust of the Israeli people; but on the other hand it seems equally improbable that an Israeli leader should ever win the complete trust of the Palestinians. I’m guessing that this design decision reflects the fact that Palestine will really be a nation when the rest of the world considers it to be one… regardless of what the Israelis think.)

The game shows you two numbers, which represent your level of political support in each group to which you are responsible. You start with both at zero, and the numbers can vary from –50 to 100. To win, you have to bring both up to 100. You lose if either number drops to –50. As a result, you cannot act only in your own people’s interest; you have to take a broader view. That alone makes the game unusual and interesting.

Every few days you can take an action or respond to a recent event. Some events are positive or neutral, but many are acts of violence by people outside your control – often Palestinian militants, sometimes extremist Jewish settlers. Each side’s options are divided into security measures, political actions, and construction initiatives, and there’s a wide variety of choices to make.

The Israeli side has the benefit of more money and direct control of those issues that most strongly affect the Palestinians: curfews, border controls, trade restrictions, and so on. The Israeli PM can send or withdraw the army at will, bulldoze Palestinian homes, order missile strikes, and bring a great panoply of security measures to bear. But he can also, after suitable diplomatic maneuvering, invest in Palestinian reconstruction and infrastructure, thus improving the quality of life in his volatile and hostile neighbor. I found the Israeli side comparatively easy to play, even on the highest difficulty setting, simply because it has the most flexibility.

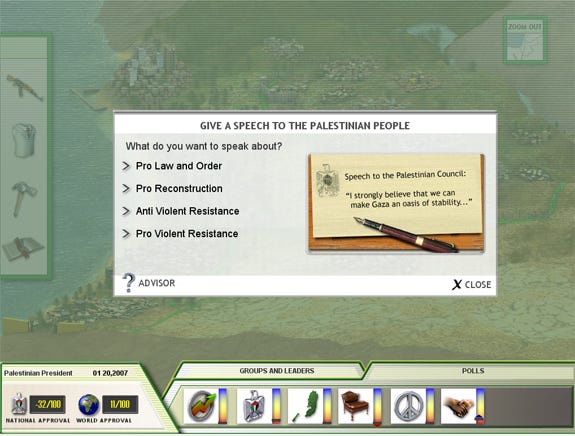

The Palestinian President, on the other hand, has to beg for just about everything: money from the world community for domestic projects, and security concessions from the Israelis. At the beginning he has very little actual power – which correctly reflects the real situation, as we can see in the headlines. He can make aggressive speeches, but that’s the limit of his overt military force.

If you’re playing the Palestinian side, the game doesn’t let you attack Jewish settlements or send suicide bombers to Israel. The Israeli PM can be a hawk or a dove, but the Palestinian President has no choice but to be a dove. I suspect that this was a political decision by the designers: a game that let you launch suicide attacks against civilians would raise too much of an outcry. As the Palestinian President, the only really violent action you can take is against your own militants – the assassination that I mentioned at the beginning. Winning from the Palestinian side requires a great deal of careful diplomacy, and a lot of sucking up to third parties like Egypt and the European Union, for mediation and financial support.

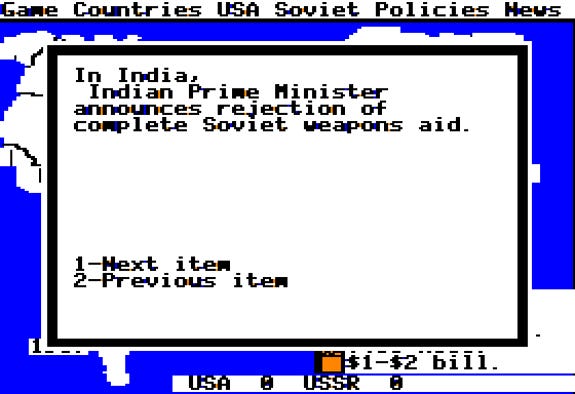

The only other political computer game I’ve ever played that had this level of subtlety was Balance of Power, which I consider one of the greatest games ever made.

Balance of Power was a zero-sum game: the object was to maximize the United States’s geopolitical prestige at the expense of the Soviet Union, or vice versa. You had to be careful not to ignite a nuclear war, but apart from that, the more you humiliated the other guys, the better. It, too, was asymmetric: the United States had loads of money and rich friends, but relatively few troops, while the Soviet Union had huge armies but very little money.

The Chris Crawford-Designed Balance of Power (Mindscape, 1985)

PeaceMaker, however, is not a zero-sum game, and it’s a richer and more difficult challenge. You have to achieve a win-win outcome, and that’s hard when many actions that your own citizens approve of will be deplored by the other side, and vice versa. The trick is to identify those actions that benefit one side without hurting the other too much, and I know what they are, but I’m not going to tell you.

No matter who you play as, you’ll often get accused of being soft on the enemy, especially by the more radical members of your own government. But since the game is about making peace and specifically rewards those efforts, there’s little point in being a hawk on either side. I tried it. I lost in about five minutes flat.

You might be wondering where targeted assassinations fit into a game called PeaceMaker. It may be about peace, but it’s far from saccharine, and you can’t win by wringing your hands and asking everybody to be nice. One of the clearest lessons of PeaceMaker is that extremism is bad for everyone – the extremists’ opponents, obviously, but their own side as well.

Militants don’t care about peace; they only care about victory at all costs. In the game, the best solution is for each side to squelch its own militants as best it can, and to use restraint in its responses to enemy attacks. The Israelis have to suppress their militants in a democratic context; the most they can do is arrest them. The Palestinian President can assassinate Palestinian militants, but he risks touching off a civil war among his own people if he doesn’t enjoy much popular support at the time.

PeaceMaker illustrates some of the hardest lessons of leadership of all: that tough decisions are not always popular; that what the public demand in the short run isn’t necessarily the right answer in the long run; that responding with overwhelming force to punish every outrage produces nothing but more outrages. Knee-jerk reactions usually fail. In a political conflict you sometimes have to allow killers to get away with it for the greater good, especially when your mechanisms for going after them are likely to hurt innocent bystanders. This decade’s terrorist is next decade’s statesman, as happened with both Menachem Begin and Yasser Arafat.

There’s a great deal to learn from the game, both about political processes and in terms of simple facts about the situation. (I didn’t know, for example, that the Gaza strip doesn’t even have control over its own water supply.) The game will be invaluable in the classroom, if students, teachers, and perhaps above all parents and school boards approach it with an open mind. PeaceMaker does not praise and it does not condemn, and for that reason I’m sure there are those who will condemn it. But if it were to take sides or get preachy, it would fail.

Instead it does something wiser and more useful: present the player with tough moral choices and then show the consequences of his actions, with visceral realism. Some will quibble about whether its internal mechanics are really accurate or not, but I think the designers have gone out of their way to be evenhanded and to attribute goodwill to both sides – perhaps rather more than either side deserves. They do want the game to be winnable, after all!

Can PeaceMaker achieve peace? No. That depends on the hearts and minds of the people who live in the Middle East – both in the affected areas and the neighboring countries too. Can it promote peace, which it states as its goal? Definitely, if it reaches a wide enough audience. Impact Games wants PeaceMaker to be more than merely a classroom tool; they hope it will be a genuinely popular game and a springboard for discussion among many people, and to that end they are releasing it in English, Hebrew and Arabic versions.

PeaceMaker is fun – challenging, tense at times, and extremely well-presented. But it’s also an important game with the potential to enlighten people about one of the great issues of our time. That’s a noble goal and one to which I would like to see more designers aspire.

----

Announcement! After many requests, I’ve finally created a database – well, OK, a file – of Twinkie Denial Conditions on my website, so they’re all in one place. You can read it on the page called No Twinkie Database. And I’m still collecting up game design mistakes for this year’s column, so if you know of one that’s not already on the list, send it to me at [email protected].

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like