The designer is god--or the devil--in The Talos Principle

The Talos Principle presents players with theological questions as well as puzzles. 'The Garden of Eden is a perfect fit for a story about creating a new intelligence,' says co-writer Jonas Kyratzes.

There has always been a kind of God/creation relationship between developers and players. The developer creates a world, filling it with life and shaping challenges in it for the player to overcome. The developer then seeks to know if the player is worthy of reward through gameplay, tasking players with solving problems, be they through violence or thought. If you prove deserving, you finish your life's story, achieving the highest of glories: a Thank You For Playing. It wasn't Jonas Kyratzes' goal to capture that relationship in the provocative puzzles of The Talos Principle, but his work as co-writer did bring up some thoughts on theology and video games.

You're just minding your own business solving puzzles in The Talos Principle, wandering around a garden looking for the approval of a disembodied voice who keeps talking about whether you're worthy or not. And then someone else suggests that maybe you ought to do something the voice doesn't want you to.

The story isn't really trying to hide the Garden of Eden theme.

"I am utterly fascinated by that part of Biblical mythology," says Kyratzes. "The philosophical implications, the contradictions, the elements of older theologies still present in the text, the way all of this has been reworked and re-imagined over centuries. It's a very rich source of imagery and ideas and a perfect fit for a story about creating a new intelligence."

The god/creation relationship at work in the Garden of Eden story frames the relationship between developer and player. On some level, every game developer is a deity of sorts, tasked with creating life, giving it a world to exist in, and providing it with some means for its existence to feel fulfilling.

"On some level, every game developer is a deity of sorts"

Maybe you create a beautiful island to explore, or maybe you create a city where the streets are filled with grime and dangerous thugs that players have to beat up to create peace, or maybe your world is a box that tasks players with rearranging tiles to form solid lines. No matter what, you've created this pocket of existence with its own rules, physics, stories, and existences.

You have become the god of these places. You have limits in creating your realm, though, as you must make it sustain the digital lives that will be inhabiting it.

What would make for a fulfilling life for a fictional, digitized being and the person controlling it? What makes players so willing to jump into the worlds a developer creates? It's something, as players, you've been doing since you started playing video games. It's something you've been doing since the first time put a round peg in a round hole as a child.

"Humans are problem-solvers. It's an essential part of our nature and something our entire civilization is based on," says Kyratzes. "What you do in your everyday life isn't that unlike what you do in this game."

The connection here is that humanity has always loved games and problems. We seek solutions when we are presented with a challenge. So, when a game gives you a series of problems, you hop right in and get to work solving them. Over time, you get curious as to why these problems exist to begin with. You start taking on larger problems, asking the overarching questions about why the game world wants you to solve these puzzles. Your curiosity drives you further through The Talos Principle, mimicking that damning moment in the Garden of Eden as well as the kind of attitudes that motivate us to get through the crises and troubles of our everyday lives. We just want to know, no matter how much trouble it gets us into.

"The Garden of Eden a very rich source of imagery and ideas, and a perfect fit for a story about creating a new intelligence."

"The interactive aspect of games means they lend themselves particularly well to exploration, which includes exploration of texts, themes, and ideas," says Kyratzes. "Games achieve much of what they do through worldbuilding."

What is more exciting to the imagination than a place where anything can exist, any rule can be created or broken, and worlds can be created out of nothingness? The game world is a place where anything can occur, and as players, we want to see those things. It might be as simple as "What's to my right?", but the player still craves this information. They wish to know what else is out there. What challenges will they find beyond the next loading screen? Curiosity, even for something that could cause us trouble, continually drives us forward.

Here, the developer can be the benevolent God or the snake with the apple. Perhaps knowledge can be gained through a simple walk, reading documents and looking at lost photographs as you meander through a countryside at dusk. Paradise is here for you to soak in.

More commonly, we're offered the cursed fruit. You want to know how the story ends? Fight through a few hundred of these soldiers, enduring death dozens of times. You will come to know all the game's storyline, but struggle and suffering will meet you. The game's God will not be kind to you along your journey, for you want the forbidden knowledge.

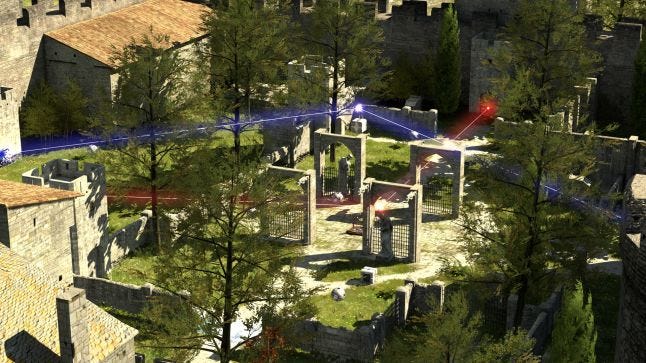

The Talos Principle provides that tantalizing knowledge in a variety of ways, encouraging players to think and explore on different levels (or mess up and get blown up). The puzzle gameplay elements draw upon our natural desire to solve problems and to seek out new challenges. The texts, each hidden more deeply than the last, create a curiosity to understand more of the narrative that lead us here and the meaning behind it all.

"The modern-day texts explain the actual science fictional purpose of what you're doing, the philosophical texts comment on the importance of problem-solving to human beings and put your actions into a greater framework of human history and evolution, while the mythological texts give meaning(s) to journeys like your own via the parallels that can be drawn," says Kyratzes. "Everything interconnects, everything comments on everything else, so you can explore a web of meaning in the same way you explore the game's spaces."

It is all built to draw the players in and make them crave more. Knowing the full story at the beginning would not carry the same lure as steadily learning it. Our curiosity has always driven us. We crave the journey to knowledge, the possibility of another puzzle to solve with our intellect, and that feeling when we piece together the information we have to unlock the mysteries of our own existence in the game world.

We need to know why. We're rarely content to simply 'Be' in the game's world. We ask that our god gives us answers and challenges us. So, it becomes up to the developer to provide us with those answers in a fulfilling way. Some way that helps us feel like our presence has meaning, and that our knowledge is earned.

When we're told not to enter the Tower in The Talos Principle, everyone involved knows what the player will do. We're going in. Because we need to know why.

The Talos Principle uses its mythology as an allegory for the games we play, and how we come to our developer gods for wisdom no matter how much they might punish us for it. We'll break ourselves on the rocks for a "This Story is Happy End" because we have to know, even if the pursuit of that knowledge will make us break expensive controllers along the way.

The Garden of Eden is an interesting theme for Kyratzes, but his work in The Talos Principle says more than words of fiction about an artificial being. It also speaks to the people holding the controller The game shows them an often aspect of the relationship between player and developer. It reminds them that it is their curiosity that brought them to these imagined shores, and that part of them craves the approval of the coding deity that has created it. They do so through besting the developer's challenges, each a step as the developer reveals more of the splendor of their world.

"My main concern is always humanity - as a species and as a concept." says Kyratzes. It shows through his story of an intelligent robot, one through which we can see ourselves, as machines dropped in wondrous realities built to hinder and inspire us in equal measure. The Talos Principle shows us that our curiosity is a part of what defines us, and that it is what draws us to new worlds, even ones that only exist in the imagination of another, brought alive through code. Worlds built by (sometimes) benevolent gods, carved out in the hidden language that can form realities from nothing.

"In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God." John 1:1.

The word as code - developer as deity. And we, though our curiosity, are only too happy to come bear witness.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)