Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In his debut feature for Gamasutra, <a href=http://www.lostgarden.com/Directory.htm>Lost Garden</a> blogger and industry veteran Daniel Cook analyzes just how "...understanding the genre lifecycle trends can help you strategically position your game design for an improved shot at success", with many concrete examples.

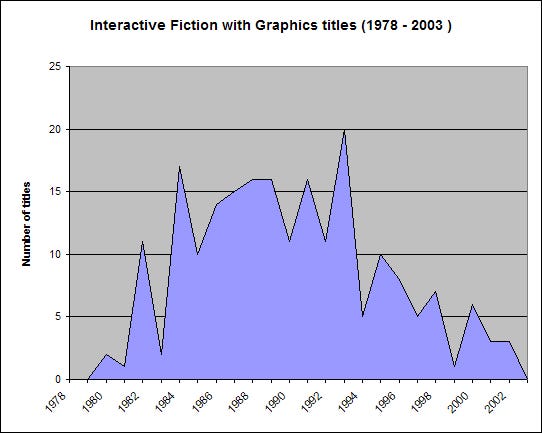

In 1994, encyclopedic game site MobyGames lists that 20 graphic adventure games were released. By 2002, the number of titles had plummeted to 3. The halcyon days of the graphic adventure genre are now long past and many of its descendants are relegated to a niche status in the modern gaming market.

This is all part of a much broader trend. Genres can be treated like product categories that evolve through a predictable series of life cycle stages. They rise in popularity and then decline. Along the way, both the needs of your users and the competitive dynamics of the market shift quite dramatically. Understanding the genre lifecycle trends can help you strategically position your game design for an improved shot at success.

Product categories

A product category is a set of products that serve customer needs in a similar way. For example, most people have the need to clean their teeth. Two major product categories surrounding this need might include electric toothbrushes and manual toothbrushes. They both solve the same basic problem, but they do so using very different techniques and each present a unique and clearly differentiated value to the customer.

Product categories matter to your business.

Customer defined homogenous markets. Many customers are trained to think about satisfying their needs in terms of product categories. They don’t think, “I need to clean my teeth.” They instead think, “I should pick up a toothbrush.” Product categories are shorthand in the customer’s mind for a very specific set of benefits, usually ones derived from their past experience with a similar product. Releasing products into established product categories increases your chance of releasing a product that serves real customer needs.

Locus of competition. Product categories are filled with similar products targeting similar customers. Customers are inclined to substitute seemingly similar products. In the game market where the purchase of a title means that it is highly unlikely that a customer will buy another similar title for multiple months, this competition has a strong impact on sales. Understanding the dynamics of your product category better than your competitors is a strategic advantage.

Games happen to be products that serve a person’s need for entertainment. We may think of them as art, political statements, idle frivolities, etc, but commercial games are products first and foremost. As products, they have product categories just like any other product. It can be a bit of a leap to transition from thinking about toothbrushes to platform games, but the fundamentals hold true.

How do product categories map onto games?

Game genres are the most common way to splitting games into product categories. A game ‘genre’ typically refers to group of titles that share the same core game mechanics. Instead of ‘Romance’ and ‘Mystery’, we have ‘first-person shooters’ or ‘2D jumping and exploration’ titles. Day of the Tentacle and Monkey Island have radically different settings, but players understand that they both belong to the same game genre due to their similar play styles.

LucasArts' timeless graphic adventure Day of the Tentacle

Like most product categories, genres are ultimately defined by the customers. A customer purchases a random game and discovers that it fits their entertainment needs nicely. Since most individual games have a relatively short burnout period, the player returns to the store seeking another similar game. Often, they’ll find that the sequel is not yet available so instead they pick up a similar title.

Occasionally, they’ll come across a game with the same brand, but with a different set of mechanics. Perhaps someone decided to make a Kings Quest 3D action game instead of an adventure game. The customers are often disappointed. For many game players, brand alone was not a meaningful measure of value.

I find the strong connection between game mechanics and product categories quite fascinating. A very profitable segment of customers believes, despite all our effort spent on innovation, branding, packaging and licenses, that similar game mechanics are the defining characteristic of gaming value.

Genre lifecycle

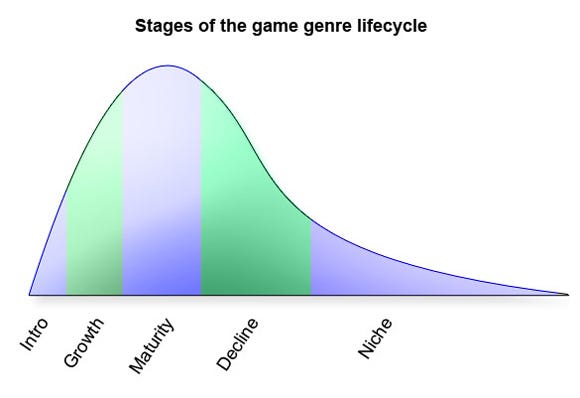

Genres evolve over time as players discover, fall in love, grow bored and then move on to other forms of entertainment. The life cycle of a genre follows a pattern often found in other product categories throughout our capitalist landscape.

Introduction. Early on in the birth of a genre, the core mechanics that define the genre are introduced. Titles such as Zork contain early examples of what would evolve into the core graphic adventure mechanics. This early stage is quite fuzzy by its very nature and picking innovative seed titles that will blossom into a new genre is a difficult art.

Growth. Follow-up titles begin appearing on the market. They experiment with the initial formula in order to make it more marketable. Often you’ll find genre kings emerge at this time. Genre kings are breakthrough products with the right mix of setting, gameplay and marketing that generate strong mass appeal. They dominate sales and establish the genre in the eyes of the public. Kings Quest is an example of a genre king.

Maturity. In the maturity stage, a few genre kings dominate the market and set the standards by which all other titles are judged. You see a standardization of control schemes and genre specific conventions such as the double jump or wall jump are established. Designers can rely on the fact that most gamers will understand these common concepts and they design their gameplay around them. AAA teams from large publishers are typically the only groups with pockets deep enough to win in this highly competitive, winner-takes-all market. Companies can reap vast profits, but if they are not in the top few percent of titles released, they can also lose exorbitant amounts of money.

Decline. Over time the core audience burns out on existing stagnant game mechanics. This decline can be exacerbated by platform transitions or the emergence of newer, more appealing genres. At this point the genre goes into decline with fewer titles being released into the market. Existing genre kings extend the public perception of the genre’s health, but are typically only updated every several years.

Niche. Finally, the genre dies in the mainstream market. AAA teams actively avoid the genre and the existing audience for the genres must rely on re-releases or independent games made for love, not money.

Does this work?

The genre life cycle is useful for garnering insight but is not foolproof:

Some genres, such as match-3 games, experience strong resurgences when new platforms or business models arrive on the scene.

Others, such as console RPGs, trundle on into the maturity phase with little evidence of decline.

Other genres are simply hard to track because they are still in the introduction or expansion phase and there is no commonly understood definition of the genre. For example, is there yet a Katamari Damacy genre? Alternatively, the data is simply poor. “Action” or “Strategy” tells very little about the core mechanics that ground a quality genre classification.

Namco's innovative, yet difficult to classify Katamari Damacy

However, despite these edge cases, the model holds up remarkably well. Most genres including RTS, text adventures, graphical adventures, 2D platformers and others that can be identified cleanly in historical databases like MobyGames or various review sites follow the genre lifecycle pattern when you crunch the data.

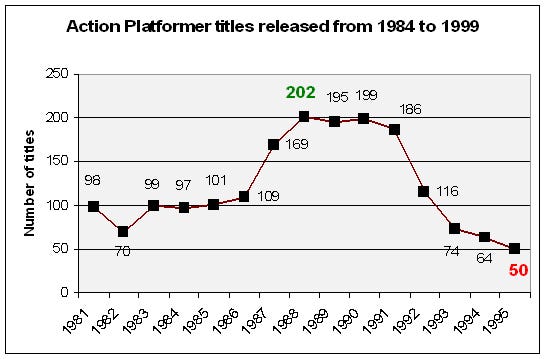

An example of the genre life cycle in 2D action platformer – Genre peaks in 1991

Using the genre life cycle to understand changes in customer needs over time

Customer demand rises and then declines over time. Some of this has to do with the general competition of new markets. However, the reliance on game mechanics as the primary source of value for the player also has strong ramifications. As players gain more experience with specific game mechanics, they go through a predictable sequence of engagement, pleasure and burnout.

Initial learning. The player encounters the game mechanics for the first time and become engaged in attempting to master them. Various game mechanics can misfire at this stage if the player ignores a mechanic or finds it too difficult or arbitrary.

Mastery. The player figures out how to manipulate the game mechanics to their own ends. They experience joy. This is the root of ‘fun’ in most games.

Use as a tool. Players use their mastery of the game mechanics as a conceptual or functional tool to manipulate and attempt mastery of higher level game systems. In other words, players gain ‘mad skillz.’

Burnout. Players see no further use in the game mechanics. Typically this occurs when the player decides that the mechanics is no longer viable as a tool in a higher level challenge.

This sequence plays out as well in the dynamics of broader market. Individual games, as collections of game mechanics, witness their players running through this sequence as well. Most players will tire of a single game given time. Genres, as collections of games that share similar game mechanics, also exhibit this sequence. Populations of players will tire of playing similar games given time. The micro-design level interaction between games and their players has a profound affect on the larger market for a game genre.

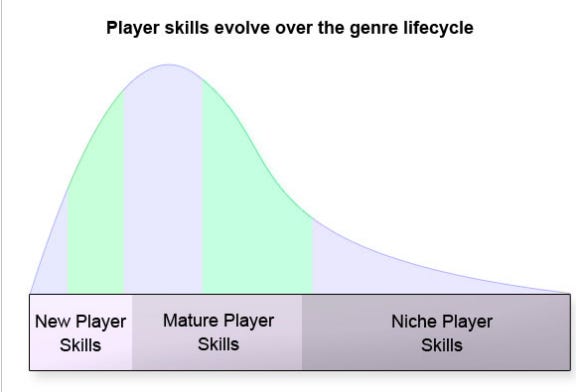

By understanding how burnout progresses, we can explain how player expectations evolve over the various stages of the genre lifecycle. In order to deliver value, you need to understand what your players want and what they can handle. This model helps us target the right level of game mechanics at the most dominant segment of the market. Let’s look at the three distinct stages of mastery that are evident throughout the lifecycle.

New player skills

Mature player skills

Niche player skills

New players

When first encountering a new game, players find everything in it surprising. Players lack the most basic skills of playing the game so the opportunities for both learning and misfires are high.

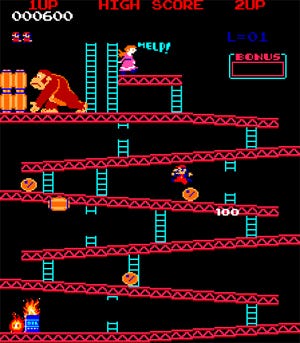

In Donkey Kong, for example, the act of jumping over barrels for the first time was a huge learning experience for most players. Though modern players might consider this game mechanic not much more than a ‘mini-game’, new players found the freshness of the mastery task was more than enough to justify a purchase. When a genre is new, it is common to witness relatively ‘shallow’ game mechanics achieving surprising successes. Even today, you can see this pattern repeat with titles like Wii Sports. For new players, the product’s value resides in their initial mastery of the new experience, not in the honing of old skills.

Mature players (aka genre addicts)

As the game mechanics standardizes, a core audience of experienced players coalesces around the genre. They’ve mastered the basics and demand that new games both honor their existing skills and offer them greater challenges to master. These passionate fans, called genre addicts, are very willing to pay for more titles that allow them to extend their existing skill set. They are also willing to promote the game. Informal networks of ‘expert’ players drive impressive sales through word of mouth. Many happily teach new players and bring them up to speed through both encouragement and social pressure.

The emergence of a cash rich, well defined, homogeneous audience is highly attractive to many developers in our failure-prone business. It is not going too far to suggest that the majority of the professional game developer industry is constructed to serve maturity stage audiences. Large teams are assembled with the goal of creating products that have a shot at becoming first or second in an established genre. In light of this business strategy, it makes sense that companies tend to value craftsmen designers and developers who are passionate about building incremental improvements within proven genres.

Unfortunately for many, genre addicts, and their practice of clustering around a small number of genre kings, create a winner-take-all environment. Second tier clones are to be expected, as are also their inevitable corpses.

Niche players

During the niche stage, the audience begins to fragment. Not surprisingly, people have difficulty maintaining nonessential skills at elite levels for long periods of time. Burnout erodes communities from within and many players lose both their skills and their urge to keep buying new games from the genre. The virtuous circle that produced the homogeneous market of gamers falters. Their addiction fades.

This leads to an interesting mix of players during the niche stage that make it particularly challenging to serve. There are three fragmented categories that emerge:

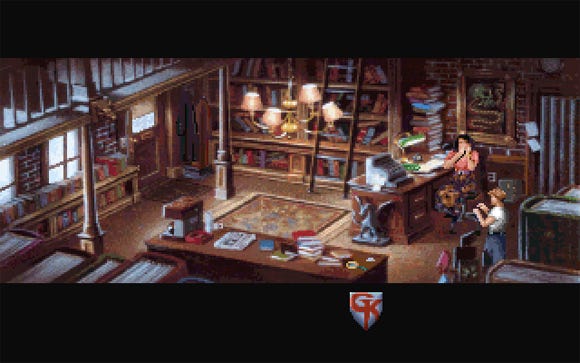

Keepers of the flame. A small percentage of players never lost their lust for the genre. The stereotypical keeper of the flame hangs out on a forum desperately demanding a remake of Gabriel Knight.

Lapsed players. A large percentage of players are lapsed players. At one point they were fervently into a genre, but now they have jobs, families and other, more exciting games that take up their time. They vaguely remember the basics, but have neither the time nor the interest in regaining their elite skills once again.

New players without a support network. Another substantial demographic are new players who are discovering the title for the first time. I’d like to imagine that selling millions of titles signals that the vast majority of the world knows how to double jump, but unfortunately this is not quite the case. Though the penetration of all game might be high, the penetration of a single genre into the broader population is often surprisingly low. When these new player discover niche titles, they typically lack the community or media contact that alerts them to the fact that there are more games of this type available elsewhere.

Sierra's supernatural adventure Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers

Opportunities: Using the genre life cycle

At each stage, we’ve seen how both the market dynamics change and the typical player skills change. Ultimately every game developer must ask “Who is my game’s audience, what are their needs, and how does my game compete?” The genre life cycle is a quick and dirty model that provides some rather useful insights into these questions.

Competitive landscape in the future. By identifying the genre stage, you can make rough estimates around a number of competing titles released a year or two down the line when your title is released. You can also start identifying and tracking release dates for genre kings.

Likely customer skills and expectations. By identifying the genre stage, you can clarify how skilled your players might be. It does little good to create a game with complex mechanics and a steep learning curve in a new genre where players are mostly unskilled. At the same time, it does little good to create a series of simple mini-games for well established genre in which players are looking to exercise and expand upon their existing skills.

Conclusion

It is perhaps mildly flippant to note that there is a big capitalist world out there full of thousands of industries that have been releasing products for generations longer than the game industry. The ‘genre life cycle’ is merely the well established product life cycle concept applied to the game industry. This is business 101 for many companies, yet I find that it is a surprisingly fresh concept for many game developers. Traditionally, we know that some product categories are taking the industry by storm, but there is rarely much discussion about why this situation might be the case.

Because we have poor predictive models of how our product categories evolve, there is a tendency to make decisions based off what is happening at the beginning of product planning. Yet, when the game is released 2 or 3 years down the road, the market has shifted, customer expectations are different and the livelihood of many a talented and amazingly hard working developer is harmed.

It is currently common for companies to spot an emerging genre during the expansion stage only to release several years later during the maturity stage. Titles that might have become staples of the genre are instead relegated to B-grade status when they come face to face with entrenched genre kings.

Heaven forbid that you started developing the greatest genre king adventure game in the mid 90’s. Your large development budget, mature gameplay, and expensive branding campaign would have met a remarkably anemic reception upon release a couple years later. The magazines might proclaim that your title to be one of the best of all time, but the customers just weren’t there any longer.

I’m struck by this quote from Bill Roper when he was asked about the canceled WarCraft Adventures from 1998, deep in the decline stage of the adventure genre:

“I think that one of the big problems with WarCraft Adventures was that we were actually creating a traditional adventure game, and what people expected from an adventure game, and very honestly what we expected from an adventure game, changed over the course of the project. And when we got to the point where we canceled it, it was just because we looked at where we were and said, you know, this would have been great three years ago.”

Blizzard's cancelled WarCraft Adventures: Lord of the Clans

Considering the poor market reception of competing high quality titles like Grim Fandango, perhaps cancellation was a wise choice. Sometimes simply making a great game is not enough to ensure market success.

It is worth our time to borrow a few analytic tools such as the product life cycle and apply them to our wonderfully vibrant industry. By doing so, we gain a conceptual framework that lets us expand our decision making beyond what is currently ‘hot or not’ and start taking note of previously unseen opportunities and pitfalls.

References

The game genre lifecycle (parts 1-4). Some early articles on the genre lifecycle.

What are game mechanics. A more in depth description of game mechanics and how burnout affects players.

MobyGames. An archive of older games and their release dates.

A discussion of Warcraft Adventures.

http://www.gamespot.com/features/pcgraveyard/p4_04.html http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warcraft_Adventures:_Lord_of_the_Clans

The history of CRPGs. This historical article gives a blow-by-blow account of how the computer role playing game genre evolved and fragmented over time. Note the numerous mentions of fan betrayal when the developers change the core mechanics of their titles. Over time, the ‘traditional’ CRPG genre fall into the niche stage and is supplanted by the 2D action RPG (of which Diablo was the genre king) and the 3D action RPG (where Bethesda’s various titles were genre kings).

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like