Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this important essay, former journalist and current EA producer Jim Preston dispels the illusion of an 'art club' that games aren't allowed to enter, suggesting that diversity has made the 'games as art' debate meaningless.

[In this important Gamasutra essay, former game journalist and current EA producer Jim Preston dispels the illusion of an 'art club' that games aren't allowed to enter, suggesting that diversity has made the 'games as art' debate effectively meaningless.]

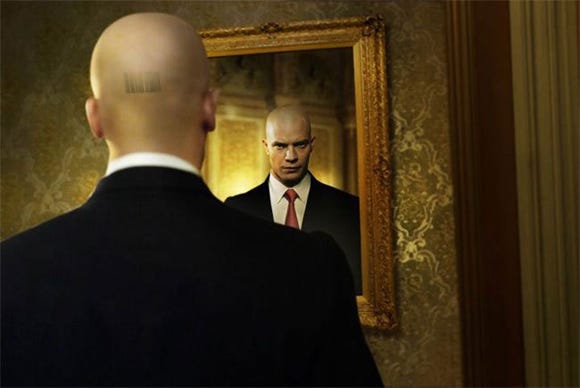

Last November Roger Ebert reviewed the film Hitman (pictured below) and raised the ante in his ongoing low-stakes game of "is it art?" with video gamers. Instead of simply declaring, as he has done in the past, that videogames are not art, Ebert goes even further to declare that videogames "will never become an art form." The claim that games aren’t an art form isn’t controversial, even among many gamers. But to take it to the next level and deny that they ever can become art is, well, just plain ol’ mean.

Naturally the reaction among gamers was the righteous fury of the deeply transgressed. Many noted that Ebert actually liked Garfield: The Movie while others pointed out the devastating ravages of senility. The desire to be considered an art form, and to get all the benefits of legitimacy that come with it, is natural for any hobbyist. The problem for video gamers, however, is not with Roger Ebert; the problem is that gamers don’t understand the disheveled state of "art" in America.

Most gamers think of their plight this way: there’s this really great club downtown called the Arty Party and all the cool people are in it. George Clooney is getting drunk with Oscar Wilde; Chopin is playing foosball with Allen Ginsberg; and Picasso is hitting on Emily Dickinson -- it’s the best.

Meanwhile, we gamers are out here on the sidewalk in the rain with the comic book guys and the graffiti sprayers and we can’t get in because that cranky bastard Ebert won’t let us through the door. Ebert, and others like him, man the door and glower at us, not letting us in to this one big party.

The problem with this picture is that it isn’t even remotely close to reflecting the state of art in 21st century America. To think that there is a single, generally agreed upon concept of art is to get it precisely backwards. Americans' attitude towards art is profoundly divided, disjointed and confused; and my message to gamers is to simply ignore the "is-it-art?" debate altogether.

Note, however, that I am not saying anything about art per se, or anything about art in any other culture. Rather, I would like to suggest that the U.S.’s constant influx of immigrants, exiles, and refugees has led to a current artistic landscape that is so widely varied that the "is-it-art?" debate is almost meaningless.

Our current cultural attitude towards art is like an enormous cocktail, with so many ingredients added over time that it is almost impossible to digest the final result.

A quick and crude history would be familiar to all of us: the early European settlers and merchants brought a broadly Christian conception of art; the slave trade injected African oral traditions and rhythms that would lie murmuring underneath the surface for decades; the antebellum and agrarian South fully embraced a neo-classical view of art.

The turn of the century saw the rise of the Blues and Jazz from the Mississippi delta; the second World War brought a wave of European thinkers and artists, many of them avant-garde; the post-War era witnessed the rise of rock ‘n roll and abstract expressionism; and the GI Bill sent (and still sends) unprecedented numbers through college, leading to a great blob of theorists who are forced by the economics of higher education to dream up more theories of art or perish.

The current state of affairs may be wonderful, weird, or woeful depending on your position, but few can argue that it is cohesive. In fact, many of our current conceptions of art are more than just in tension -- they’re nearly contradictory. Consider the classical conception of art, where a metaphysical realism undergirds a style of art that values balance, accuracy and beauty.

Nature as it reflects both the human and the divine is the primary, but not sole, object of this art style. This mode of art is still alive and well today. Classical music, although certainly not ascendant, is still played in orchestras throughout the nation; masterpieces by Van Gogh or Leonardo draw throngs when they tour; and the name "Rembrandt" is still synonymous with "artist."

However, the dominant aesthetic posture of contemporary American society is not Classical. It is without a doubt a kind of mainstream Romanticism provided by Rock ‘n Roll. Rock’s penetration into the American consciousness is almost total. No artistic spirit has had a more effective ambassador than Romanticism has had with Rock.

The emphasis on energy, emotion, rebellion, and individualism has transcended the lyrics to become the everyday culture. The message of rock can be heard while shopping for groceries; it’s not just Iggy Pop but also Carnival Cruise Lines that have a lust for life; and Cadillac, along with The Doors and William Blake, can help you break on through to the other side.

The idea of the small, 1950s town that is awakened from its dogmatic slumber by the transformative powers of dancing and rock 'n roll has become a sort of national myth -- a defining narrative where everyone gets to be a rebel.

Yet consider how rock and classical -- or more accurately, symphonic -- music are almost diametrically opposed on key philosophical issues. Both art forms are quite snobbish, for instance, but on the same axis with different criteria. Symphonic music values qualities like patience, sensitivity, subtlety and harmony. It takes training or education to truly appreciate great symphonic music, and some might go so far as to say it requires proper breeding to truly be open to it.

Rock’s snobbishness, on the other hand, despises so-called good breeding, and places all emphasis on authenticity to the Romantic credo. Rock is committed to energy, vitality, youth, the celebration of the self, where the only possible sin is the not being true to your authentic self. One need only flip through the pages of any rock magazine to see the sneers the artists, journalists and audience have for commercial sellouts.

But perhaps nowhere is our deep divide about art clearer than in the strange lines of contemporary painting. The current film My Kid Could Paint That is only the most recent version of a century-long debate on what painting is to become in an age of photography and film. To some, the film’s 4-year-old star is a prodigy, the kind of artistic genius that visits us once in a lifetime.

To others, she is the latest reductio ad absurdum of an artistic expression that is almost indistinguishable from gibberish. And it’s not just the philistines who cry foul. As Tom Wolfe pointed out in The Painted Word, you’re going to need a theory in order to make sense of Pollock, De Kooning or Rothko.

These same divides can be found in other art forms. Chuck Palahniuk is to some a rare literary artist, and to others he is a symptom of deep cultural decline. Quentin Tarantino’s constant recovery of cinema’s discarded detritus makes him a post-modern hero to hipsters, and a sort of cultural bowel obstruction to traditionalists.

What are video gamers to make of this? If there really is an art party, and we need to get someone’s approval to get inside, who is it? Roger Ebert? Harold Bloom? Johnny Rotten? Michael Kimmelman? Tom Wolfe? Does it really matter?

For my answer, consider this example. In May of last year, the Washington Post tried an experiment about the appreciation of art. They hired Joshua Bell to bring his Stradivarius and play works like Bach’s "Chaconne" in a Washington D.C. subway station on a busy weekday morning.

To put it another way, what would happen if you were to take arguably the greatest living violinist and have him play to busy commuters with a perfect instrument some of the greatest music every written? Would they recognize that perhaps the very apex of Western art was appearing in their midst?

As it happens, they did not. Only a handful of people even stopped to consider Bell, and only two truly recognized what they were hearing, probably due in large part to having been trained in music. In examining the question of why more people didn’t realize what they were hearing, the article cites Mark Leithauser, senior curator at the National Gallery.

He argues that if he were to take $5 million dollar work of art, remove it from its frame, and hang it up at a local restaurant with a price tag of $150 on it, almost nobody would recognize it as a masterpiece. The context in which we view the art, says Leithauser, goes a long way towards creating our appreciation of it.

Or if you are Marcel Duchamp, context goes all the way. Let’s not forget Fountain, his urinal that became art in 1917 for the simple reason that it was put in a museum. This, suggested Duchamp, is what makes art, art: how we treat it. How do we know this urinal, this "readymade", is a piece of art? Because it is in a museum, and that’s where we keep our art. How fitting is it that in 1993 at a museum in southern France one of Duchamp’s artistic admirers paid his highest respects to a reproduction of the piece -- he pissed on it.

My suggestion to my fellow gamers is not to piss on Roger Ebert, as tempting as that may be. Instead of adopting a philosophical or aesthetic strategy, we should adopt a political one. Even if I thought Ebert had a coherent conception of art, there is little to be gained by engaging him in an essentialist debate.

My suggestion to my fellow gamers is not to piss on Roger Ebert, as tempting as that may be. Instead of adopting a philosophical or aesthetic strategy, we should adopt a political one. Even if I thought Ebert had a coherent conception of art, there is little to be gained by engaging him in an essentialist debate.

Instead, we should learn from Joshua Bell’s example and focus on creating the conditions in which video games can be viewed as art. And the good news is we are already well on the way to doing so. Orchestras across Japan, the U.S. and Europe have begun to perform concerts of videogame music.

Versions of Pong, Dragon’s Lair and Pac-Man are on display in the Smithsonian. Academic conferences about videogames are emerging. Cosplay. Machinima. Penny Arcade’s Child’s Play. Etcetera.

As the video game generation grows older and more influential, the "is it art?" debate will be won by context and simple attrition. Gamers will have grown up with them, and the cranks in meatspace will slowly die off.

None of this is really to say that games are in fact art (although Duchamp himself thought that one game, chess, was purer than art). Instead, I am merely suggesting a strategy about how games could actually come to be accepted as art. And as for Roger Ebert, my suggestion to my fellow gamers is the same as my suggestion to my fellow movie-goers: ignore him.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like