Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Following Jim Preston's controversial Gamasutra feature on games as art, Crash Bandicoot, Gex and Uncharted designer E. Daniel Arey responds with a fired-up, in-depth piece on why the art inherent in gaming matters.

[Following Jim Preston's controversial Gamasutra feature on games as art, Crash Bandicoot, Gex and Uncharted designer E. Daniel Arey responds with a fired-up, in-depth piece on why the art inherent in gaming matters.]

I am not in the regular habit of writing wordy rebuttals to developer opinions on game forums about our industry’s place in the world. Let’s face it, there are ten thousand myriad points of view on any one subject in this biz, and many are mostly right (to varying degrees) at least some of the time. But I was deeply moved to respond to a recent Gamasutra installment from EA producer Jim Preston’s essay “The Arty Party."

It wasn’t the overall philosophy of Mr. Preston’s essay per se that upset me, and I’m sure he is an outstanding producer and game developer. In fact, his final assertion that we are moving toward a promising future is correct.

What did concern me was his overall seemingly static vision for our industry, and the almost jaded approach to the current value of what we call art. You can add to this the Gamasutra editors' choice of title for the related news story, 'Forget Art, Let's Game', which - while serving its purpose as a provocative siren’s call - seemed to once again proudly proclaim games as nothing more than they are, or ever will be, as an entertainment pastime that is limited and unable to evolve or adapt.

Before I continue, let me make it clear that I do not intend for this to be a semantic debate about what is art and what isn’t? Nor do I care where the line between art and entertainment is drawn, or by whom.

Shakespeare certainly walked that line well. Books and films trip over themselves often to become something like art. Theater will gladly tell you they are art. What I do know is that every entertainment medium must push its boundaries to evolve and survive, otherwise they become static and irrelevant.

Is that too bold of a statement? I think not, when you pull back and look at the wide evolutionary timeline of entertainment as a continuum. One simple example of this Darwinian struggle was the new discovery of the photo camera - which challenged the artists of that time in their ability to recreate a landscape in perfect fidelity.

Is that too bold of a statement? I think not, when you pull back and look at the wide evolutionary timeline of entertainment as a continuum. One simple example of this Darwinian struggle was the new discovery of the photo camera - which challenged the artists of that time in their ability to recreate a landscape in perfect fidelity.

It took bold action from the Impressionists to respond and evolve painting to a new and wonderful form by saying - “we are not simply trying to represent a thing, we are trying to capture its light and the feeling of the moment.”

That was art responding in a powerful way to a simple and mundane circumstance, and this response, however misguided some thought of it at the time, created a thing wholly new and beautiful.

But the question more often asked is does art really matter? I would certainly think we would all be the poorer for not having Homer, or Shakespeare, or Monet, or Mozart, or Yeats, or Hitchcock, or Feynman, or Bunten, or Meyers, or Wright.

We can let the academics debate whether “art” as an applied aspect to any form is important for society and its legacy. I am not here to debate the “disheveled state of art in America”, as Preston puts it.

I for one believe art is always alive and deeply important, no matter what, and often despite, the state of society. It is a fundamental human need. Preston’s rather cynical example of the violin incident in the subway where no one noticed “the art” has no bearing on this discussion. Whether anyone recognizes a virtuoso playing a perfect piece of music on a perfect violin in a dank New York subway is irrelevant.

I for one believe art is always alive and deeply important, no matter what, and often despite, the state of society. It is a fundamental human need. Preston’s rather cynical example of the violin incident in the subway where no one noticed “the art” has no bearing on this discussion. Whether anyone recognizes a virtuoso playing a perfect piece of music on a perfect violin in a dank New York subway is irrelevant.

The fact remains that it did happen, and to me that was art in its purest form. It was a personal expression despite the odds - set diametrically opposed to the moment - which became something to me, even if just to imagine.

Picture it – a brilliant and lonely violinist playing a sublime canon in a dark and cold concrete subway platform, and yet no one is listening to his call. I love that image!

However you fall on the subject, arguments about art’s impact or awareness can be left to the academics, and in my opinion these questions lead to nowhere. We’ve all heard the old phrase “I know it when I see it”, and I believe this litmus test can serve us well as the touchstone for our discussion.

I’ve heard countless calls over the years, often with good and pure intentions, that “Games are games, and we should keep them that way.”

While I fully understand and support that games are a wonderful play pastime, and that gameplay and fun are the beating heart of our business, I find these assertions to keep everything the same as a set of false boundaries that foster cynical limitations by those in power to assure the status quo is comfortable and predictable.

The real truth is, games have always pushed the boundaries and evolved on their own, right from the beginning. First they were a simply a “Novelty.” Then Time Magazine proudly labeled them a passing “Fad.” Then they were a “Quaint Pastime.” Then a “Cultural Phenomenon.” And now a “Mainstream Entertainment” medium.

In truth, video games have always grown beyond the bounds we try to impose on them. The people that make games are always pushing back to surprise us and surpass our expectations, and - yes, they will always continue to do so. That’s what makes working in games so exciting!

Just to be clear, I’m not some Andy Warhol wannabe hoping to push games and the game industry into the realm of snobbish, elitist Studio 54 midnight chic. I’ve worked on and helped design many hit games that have been firmly placed in the center of the mainstream of the industry (to the tune of 35 million units sold and counting.)

I know how to make a best selling game, and so does Mr. Preston at Electronic Arts. In fact, EA is the center of gravity in our business, and I can see where from their point of view, nothing should change and everything is just fine as it is. But as is always the case, and since Mr. Preston is a philosopher he can attest to this, change rarely happens in the center of a paradigm, but instead occurs fitfully on its fringe, in that frothy rich, cross-pollinated soup that mixes with other arts, ideas, thoughts, and mediums.

The most profound and recent example I can think of is Pixar and Disney. John Lasseter - while working at Walt Disney Feature Animation - saw the huge potential for 3D after seeing the light-cycle sequences for the movie TRON. He was very excited by the potential of 3D, and wanted Disney to make 3D animated features.

Of course, Disney’s business and comfort zone was in 2D cel animation (with lots of data showing how that business was the right place to be), and understandably, Lasseter’s efforts to make changes were soundly rejected.

It took Lasseter having to leave Disney and co-founding Pixar to make a difference. With a lot of effort and amazing vision, he met with huge success with Toy Story - as the Pixar catalog caused a massive paradigm shift that eventually overwhelmed the 2D animation format.

It is important to remember that to make this new art form happen, Lasseter had to do it outside the dominate corporate structure, all before eventually returning to Disney in triumph - where he now heads up its Animation Division.

Lasseter didn’t set out to run Disney Animation. Nor did he set out to create a new 3D “art form.” He just followed his instincts, his passion, his hard work, and his sweat, and from that grand vision all else followed.

Ironically the concept of “games as art” was deeply coded into the original DNA of EA. The company’s name “Electronic ARTS” was a bold statement to that fact and focus. I was there in the mid 80’s when Trip Hawkins still walked the halls of a sub-100 employee, privately held EA.

Back then the company treated its developers as true artists, giving them great latitude in making interesting ideas become great games, proudly putting their developer’s pictures on the back of rock album style game covers. Trip and company knew that what was occurring in this nascent and vibrant new medium had more to do with art than it did science.

Like music, his musicians were the Danny Buntens, Anne Westfalls, and Bill Budges who pioneered our industry, all true renaissance artist creators in their time.

So where did that bold artistic philosophy go? I hope it is still alive in each and every one of us. The idea that developers are artists should come roaring back in this biz to open up new possibilities for bold and exciting new directions in tired old genres. Guitar Hero, Rock Band, and the Wii are strong selling cases in point! Bring on the crazy creators!

Let them challenge us, delight us, and surprise us with new creations and new directions! Games and gaming have always had this rebellious spirit and it needs to be reinvigorated more than ever today to fight the tired and cynical point of view that games have arrived at their one and only calling and there is nowhere left to go.

I took strong issue with Mr. Preston’s analogy that we are on the outside looking in (along with comic books) to a so-called “Arty Party.” First of all the analogy is flawed at its very core since comic books (once the pariah of society) are no longer on the so-called “outside” - ever since Superman, Batman, the X-Men, Spiderman, and others hit box office gold and multimillion mainstream film audiences learned to love these universes.

Even if that is not enough, comics arguably crossed over the so called “boundaries” into art long ago for other reasons. Whether it be the Watchmen series, or Neil Gaiman’s evocative Sandman, or for more recent examples Frank Miller’s Dark Knight and 300, many comic books have surprised and moved us, and occasionally transcended from pure entertainment to something more amorphous we call “art.” To this end, comics are the better for it.

Again, this idea that we want to be in with the art party is a fallacious construct. We already are on the inside! We are a (some would say the) major entertainment medium, commanding millions of eyeballs the world over! People with a new vision for games who wish to push the boundaries are not interested in a proverbial old-timers' party.

They care about the output of bold new ideas which grab us, move and surprise, take us to new places (like Westwood’s creation of the RTS), foster ideas that titillate and confound us, games that open and connect us (like World of Warcraft) - and entertainment that has a heart and compulsion factor that brings enjoyment and satisfaction, but does so in surprising ways. It doesn’t mean we are trying to make art in this endeavor. It simply means that great visions and great visionaries lead to great outcomes.

It just so happens I recently had dinner with Frank Miller since reading Preston’s essay and before writing this response. I asked Frank how he saw his process of creation, and he firmly suggested that he was just capturing moments.

Little life and character moments so small that they are often missed by the eye – ambivalence, jealousy, heroics, anger, fear, doubt, triumph, all can be captured and frozen with Mr. Miller’s pen (or high speed camera) in sequential frames of reference.

Great masters didn’t set out to do “art.” They set out to make something from a unique perspective. To do something a little bit different. Try a new angle, a special technique, a new way of looking at things. They find the little moments of change that mean everything.

To take an example from Miller's output, the comic and movie 300 proved to be a tour-de-force of such moments - no one who saw that movie can say those visual moments captured frame by frame weren’t “art” in every sense of the word. (Case in point, the slow motion frames of the Spartans pushing their foes over the cliffs into the sea, with the backlit rays of the warm setting sun splashing through their silhouettes.)

That was unforgettable imagery, and yes, in my opinion Art with a capital A. But more importantly, it was considered a crazy idea by the powers that be when Frank first thought it up. It was a “bad idea” before it was a huge mass market and box office success - that made hundreds of millions of dollars.

And this is my primary contention. Games, and art, and the market success we all seek do not have to be mutually exclusive. Can anyone argue that the rock band U2 isn’t an amalgam of bold artistic expression and mass market success? U2 has always pushed the limits of their messages in music, reinventing themselves, redefining their sound and relevance.

In a different medium, Alfred Hitchcock is remembered today solely for his filmic art styles, and for breaking long established methods (like killing off your heroine in the first act), but in his day his movies were a huge box office success!

In games, BioShock was a big hit last year. The product took a number of awards, including the Game Critics Awards Game of the Year. It was an FPS full of fabulously unique art, twitch shooting, somber moods, and strange locations. And it was also, yes, a piece of real Art. Ken Levine may or may not have set out to create “art” per se, but he did have the vision to make something different than your standard FPS fare.

He and his team made a game that stood out from the crowd with color, and mood, and sounds, and vocals, and music, and lighting, and a strange dichotomy of elements that made us uneasy and enthralled. It was a game that surprised and moved us deeper than most games. It had a statement to make and a mood, and it gave us an experience that provoked the mind which lasted well after the game was over. To me, that’s the definition of art.

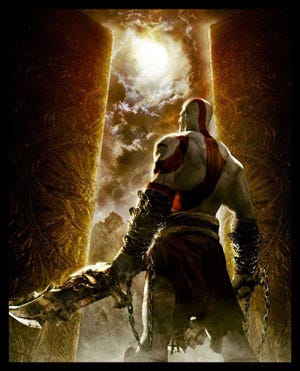

Another great case in point was in the hit game God of War, during the final boss fight - where you must protect images of your wife and daughter against various versions of yourself in the form of doppelgangers who are attacking them.

Another great case in point was in the hit game God of War, during the final boss fight - where you must protect images of your wife and daughter against various versions of yourself in the form of doppelgangers who are attacking them.

The metaphor goes as far as to have the player give up your own much needed hit point energy to save your family at the risk of running out of your own energy and dying.

Whether you call it “art” or not, that game had something to say! David and company were making a bold statement at tha moment in the midst of outstanding character action gameplay, and it was moving.

Now, I’m not talking about making art for art’s sake. That path leads to emotionally vacant spaces full of elitist dreck (like the proverbial urinal placed in the museum.) What I am talking about is not being satisfied with the status quo.

Don’t just regurgitate your last success. Let game developers follow their muse and let the “artists” on game teams speak loudly again. I’m talking about developers and publishers alike having the courage to break the mold, try something different, and combine new things with old things in new ways.

This of course means letting a few more failures happen as we try out new paradigms. It means letting something “a little strange” have a longer chance before it gets killed it in the green-light process. Can you imagine what would have happened if we had put such strangling straitjackets on Star Wars, or Platoon, or Pulp Fiction?

How about Ico, Guitar Hero, or BioShock? These great entertainment titles wouldn’t have seen the light of day, and the world would have been poorer for it. (In fact, Star Wars, BioShock and Guitar Hero had a terribly arduous road to publishing, and almost weren’t made because of the safe and sound resistance to new things.)

This often dirty and indirect process of art is more often than not a subconscious process. Many times an artist following their muse won’t even know they’ve changed the world in some small way until much later when people look back from afar. Only then will the lines of influence begin to take shape.

Neil Young often asks the question, “Have we in games reached our Citizen Kane moment?” It’s a great question to ask, and one that caries many layers of meaning. But even in its time, no one knew that Citizen Kane was a “Citizen Kane” moment. It took a singular bold vision of a man names Orson Wells to do that, and it wasn’t until many years later that his influences on other film makers became clear.

I am here to say that we just might have hit at least a small part of that higher watermark. The game Ico is a work of art and still proudly placed on many top game lists as one of the best and emotionally vibrant games to be released in the last decade. (In fact, it just won out as Gamasutra's best love story in games.)

Everywhere I go I hear Ico being referenced in game development forums and at conferences in one way or another - for its animation, for its sense of mystery, for its emotional content, and for fostering a deep connection and concern for an inanimate character. And yet despite all this praise, it was a commercial failure.

It reminds me of another business failure in its time…yes, that’s right, Citizen Kane. A movie that, like Ico, failed to hit big at first release, yet also like Ico continued to influence people long after the fact. Both Ico and Kane carried strong and artistic emotional imagery and symbolism.

Both had a narrative mystery that was never fully explained. And both, through artistic framing, shot angle, and set design, used the backgrounds as a character in the story. And in the end, I believe both have and will continue to have a strong influence on their respective mediums to come.

This is what “art” can do. This is what visionaries and mavericks can foster! This is how a commitment to something strange and new can be a catalyst for a better future. It can shift our focus, move our paradigms, redefine our discussion, reframe the truth, and open new doors to keep our industry growing. Art is as much a process as it is a result.

I understand it is a difficult thing to ask people with money, and those with control and a heavy responsibility in this industry to have a little “faith” in a world of heavy budgets and teetering P&L’s, but I am here to firmly assert that this faith and commitment to new ideas is vital for the long term health and success of our industry. It has been proven over and over in the vast ebb and flow of countless entertainment mediums. Growth and evolution are fundamental to help maintain any healthy and growing system.

Just like the Rail Barons in the late 1800’s who sat in their ivory towers and said “Why would anyone want to buy an automobile? We already have rails going everywhere people want to go!”, I say - keep an open mind about games and art, and what a true artist’s vision can do to transform a good idea into a great game, and a great game into a phenomenon.

Art and games have always been inseparable; one cannot live without the other. If gameplay is the heart of games, then artistic expression is its lifeblood, enriching us all with its changing and far-reaching wonder and power.

So yes, let’s keep making great games and having fun making gameplay that is addictive, and engaging, and enjoyable to everyone. But let’s not forget the artists who got us here, and those new artists on the horizon who will boldly help us build and define our future.

They are the artists who carry the secret map to strange new places, and they will take us to these novel locations where we can rediscover the wonder of games. These far corners are where we’ll find new experiences which, just like in the games we make, are the true treasures of adventure.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like