Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In a rare interview, Gamasutra talks to the key directors behind the 186 million unit-selling Pokemon series, talking about balancing and developing the massively popular Nintendo-backed series.

Junichi Masuda joined independent Tokyo-based developer Game Freak in 1989 to compose music and program for games. Over the next few years, the team released a few games -- first, in 1989, Quinty, for Namco, on the Nintendo Famicom (which was released in the West under the title Mendel Palace.)

The company's Jerry Boy (Smart Ball in the West) came next, in 1991. In 1991, Game Freak entered into its first collaboration with Nintendo -- Yoshi no Tamago, or simply Yoshi in the West, on the NES. Games for Sega, Victor, and more for Nintendo followed.

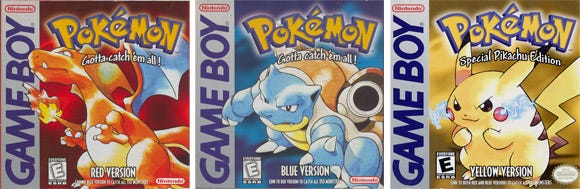

But in 1996, the company's defining title would be released -- a title so finely crafted, brilliantly marketed, and addictive that it became a global phenomenon. A title so successful that it revitalized a nearly dead platform and made it one of the most important in the world. The title, of course, is Pocket Monsters -- better known as Pokémon -- and the system is the Nintendo Game Boy.

Game Boy Color and Game Boy Advance, backed by Pokémon, carried Nintendo through the increasingly lean Nintendo 64 and Gamecube years.

And though the Nintendo DS didn't need as much help, Pokémon has been there to preserve the formidable audience built on Nintendo's portable platforms over the years and capture more converts.

Gamasutra was recently invited to travel to Nintendo's San Francisco Bay Area HQ and speak with Junichi Masuda, longtime director of the Pokémon series, and Takeshi Kawachimaru, director of the recently-released Pokémon Platinum, talking about the 186 million-unit selling franchise.

The discussion turned to the art of balancing the inherent complexity of the titles with the simplicity Masuda sees as the series' core appeal -- whether it comes down to visual direction, gameplay design, or staying true to the series' core concept: catching, training, and battling adorable monsters.

I'd like to talk about the origins of the whole Pokémon series. I know that you personally have been working at Game Freak since 1989, so that's even before Pokémon started. I wonder if you could take me back to the initial inspiration and when you first heard about the idea for Pokémon, and your thoughts about it.

Junichi Masuda: As you know, the founder of Game Freak is Mr. [Satoshi] Tajiri, so when Mr. Tajiri talked to me about the idea he had... At that time, you could connect Game Boys with a cable, and you could play -- and battle by playing in, for example, Tetris.

But for this one, he had an idea of trading monsters. When I heard about that idea, I thought it was an interesting, fantastic idea. However, you then have to realize it, and make it into a game. The concept itself was very interesting, so you could expand and see how you could develop it into one game.

When you first started with the series, you were composing the music, right? And then you moved on to directing the games later on.

JM: Yes.

I was wondering, as the series evolved, what made you want to get involved with moving on from doing the music and actually becoming involved directly in the creative side of the game?

JM: Yes, when I joined Game Freak, I joined as a music composer. However, I was also programming some games. Not the Pokémon games, but other games as well.

So when we were working on Red and Blue, I did some programming as well. I had a lot of ideas, and I wanted to engage in the creative aspect of Pokémon games. I wanted to use my skills on a Pokémon game.

At that time, when you first started up the series, I'm assuming that Game Freak was a very small company. How big was it then, and how big is it now?

JM: At that point, the different people who worked on the Pokémon games were nine people. There were other projects going on, and there were 20 people in all. Now, it's more than 60 people working on various projects.

Something that's obviously very characteristic of the Pokémon series is that there are the multiple color cartridges, which there have been since the very first one. I was wondering where that idea came from, to have multiple different versions with possibilities of different Pokémon in those cartridges.

JM: The basic concept of Pokémon is trading, so how could we make the trading more attractive? If you have a different Pokémon in your game, that's a different kind of Pokémon you can collect.

You can finish collecting all of the Pokémon based on the Pokedex. What kind of abilities can that Pokémon have? What kind of an attractive character can you create?

When Mr. Tajiri went to talk to NCL, Mr. Miyamoto actually suggested, "How about creating different cartridges? There are different Pokémon on each cartridge, and people are willing to trade the Pokémon."

Obviously it's one of the most popular games around now, but at the time, I get the impression it was sort of a slow uptake. Could you talk about watching it become more popular after it was introduced?

JM: First of all, it was launched on February 27, 1996. The game started gradually picking up.

Meanwhile, Pokémon was adapted to an animated TV show, and manga, as well as a trading card game. I was surprised that Pokémon was about to enter different media like that. That's when I realized, "Wow." Surprising.

And it took a couple of years before Nintendo put it out in America. Were you initially surprised when you found out? I think the thought was that maybe it wouldn't appeal to the U.S. audience -- at that time, in 1998.

JM: Most of the Pokémon characters are very cute Pokémon. Also, there was a notion in the Japanese game industry that role-playing games created by a Japanese company may not sell really well in the U.S.

There was a notion among everyone in the game industry; so the initial thought was that it might be difficult.

I have a friend who is a developer, and he's working on a kids' game. He's worked on several different games for kids that are developed in the U.S. He says that very often, in his observation, developers in the U.S. aren't all that happy to be working on kids' games. They'd rather be working on games more for an older audience. But I get the impression that you must be very happy to work on Pokémon, because it's so popular. Could you talk about how that inspires you, working on games for kids?

JM: First of all, we did not create Pokémon for kids. We create the Pokémon games for everybody. Everybody can play the Pokémon games, so we try to make the games very approachable. For example, we use different colors. It's not just about the text, but the visual appeal. In the end, yes, even kids can play this game.

Of course, adults might focus more on the storyline. But the main thing is catching Pokémon, and trading Pokémon. You trade Pokémon.

If you're an adult and you're trying to trade Pokémon, you might feel a little bit shy, because you're dealing with Pokémon. Maybe between kids, they're not shy about it. So maybe in that sense, maybe kids can better enjoy the trading aspect of Pokémon games.

Something about Pokémon is that it stays very true to its roots across its sequels, and it stays very simple. It didn't become super-3D, and the stories didn't become overblown as the series moved on. I was wondering, how did you stay true to the roots, and how do you balance that? How do you avoid the temptation or the pressure to pump everything up and become like Final Fantasy, or something like that, over the years?

Something about Pokémon is that it stays very true to its roots across its sequels, and it stays very simple. It didn't become super-3D, and the stories didn't become overblown as the series moved on. I was wondering, how did you stay true to the roots, and how do you balance that? How do you avoid the temptation or the pressure to pump everything up and become like Final Fantasy, or something like that, over the years?

JM: Visually, you're saying that 3D here may be possible, but I question your question that 3D is the best technique to realize the game.

The basic concept of Pokémon is that we want to attract the beginner, so that when the beginner comes and plays, if it's 3D, it's three dimensions instead of two, so it's much more information for you to take in. We don't know if that's what they want. We want the game to be approachable and easy to understand.

Also, there is a balance that we have to make. By balance, I mean, do we want to make the scenario deeper, so we have a deeper, more complicated storyline, or do we want players to collect, catch, and trade Pokémon?

That balance is always difficult, and we try to find a better balance always. But I absolutely consider it. If 3D makes the player catch and collect more Pokémon, then that's definitely the way to go.

No, I agree. I think that you made the right decision, actually, with the game, and the look. Something that I find very cool about Pokémon is that it sticks to its roots in terms of the pixel art. Even though there are 3D polygons in the DS Pokémon, it sticks visually to a very simple style. With the battles, you stick entirely to 2D artwork, still. I was wondering if you could talk about why you stick to your roots. Maybe it is just in terms of making it simple and easy to understand, but it seems to really stay true to the series and what it's been like over the years.

JM: You think that creating 2D is easier than 3D, but it's not. It requires a lot of technological understanding and technological skills. I always talk with the art director -- "What's the value is of sticking with 2D art?"

When you look at 2D, it's like a picture. You look at the picture, and it has some flavor to it. 3D, yes, you can make the object very realistic, but 2D is something you can put flavor into. That's what we love about 2D.

Every time there's a new Pokémon game, there are the two initial versions, and then later, there's a third version. Where did that idea come from, and how does that play into the design? You know it's going to happen every time, so how does that play into your game plan for creating a new Pokémon?

JM: We put so much energy into creating Pokémon video games. For example, let's take Diamond and Pearl. When we started thinking of Diamond and Pearl, especially because we were moving to the DS... the DS has lots of capabilities and lots of functions; new functions that you can utilize to adapt into the game. So many ideas.

So by the time we developed D/P, we had to give up some of the features we wanted to put into D/P because of the deadline.

Let's say, for example, in D/P's case, that the second half of the D/P development, you decide that, "There are some features that we really want to do. Let's do it in the third one."

That's how we make a decision. Ideally we wanted to put everything into D/P, but there is a deadline, so you have to make up your mind.

Now, development time between Pokémon sequels like Diamond and Pearl is quite a long period of time for games that look relatively simple. I know they're actually really complicated, but I guess the point that I'm trying to make is that most games would have a very short cycle. I want to know what goes in to that whole process. I can understand why it takes that long, but maybe not in detail. Could you talk about that process, of where you start and where you end up?

Takeshi Kawachimaru: Let me take the example of D/P and Platinum. As Masuda-san said, by the time we almost finished D/P, Masuda-san came to me and said, "Let's make Platinum. Would you like to do it?"

My answer, without thinking, was, "Yes." I put so much energy into D/P. I felt like I completed a marathon. You're out of breath, but I said, "Yes," and I started running again right away after.

As Masuda-san said, there were so many ideas that we wanted to work on. We wanted to revisit those ideas and see what we could do to put them into Platinum, so I had to go back and look at what we did with D/P, and what we couldn't do with D/P.

Also, we had to consider good reasons we should make Platinum, and why not something else. So we had to think of that reason, otherwise the product would not sell. We had to revisit the ideas which came up and see how we could apply them into Platinum.

Something about the Pokémon sequels is that they always have a lot of new elements added, whether it's new Pokémon, new types of Pokémon. I think that, even more than other games, balance is super-important to Pokémon. How do you add and balance elements?

JM: We think that the balance is one of the most important elements that we have to think of when we design the game.

We have designated staff who overview the balance of Pokémon battles. I don't know how long he works, but he spends time battling while eating or chatting with people.

That's the only way -- to actually play and make sure that the battle is balanced. It takes time and effort to make sure everything is balanced. That's something that we always care about.

And what about making sure that the different elements of the game -- when you add in whole new layers like GTS or a new region or something -- how do you make sure that those don't throw the game out of balance, in a more general sense? It's got to stay accessible to the broad audience that you spoke about. How do you make sure it's accessible, playable, and that everything works together?

JM: Personally, I don't like it when things get too complicated. I want Pokémon games to be accessible and approachable. However, you can make it complicated by adding accessible, approachable elements to it, and that would become built into something bigger. That's how we always create the game.

For the beginner players, you start by explaining, "This is how you catch the Pokémon. This is where you go for the Union Room. This is the GTS." Everything is introduced in a certain way, and in the end, by the time you complete the game, you realize how much you know.

TK: Normally, for RPGs, you come up with the plot, and that's the storyline that you have. And definitely, we do have that. But also, we have another plot, to talk about the functions of the game.

So we create the plot based on the functions and where we should put them. "This new function, this new element, here, there..." In the end, it becomes an entire big plot.

JM: That's why there is the Battle Frontier, after the game. That's where the best of the best trainers go and battle.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like