Tales from the making of Jedi Knight II: Jedi Outcast

The developers of Jedi Knight II: Jedi Outcast look back on the original game's development and how much has changed in their game-making careers.

Last month, Aspyr Media rereleased a port of Jedi Knight II: Jedi Outcast on the Nintendo Switch and PS4. It was a particularly notable rerelease not just for fans of Star Wars, but as an artifact of a particular era of game development and the development history of now Activision-owned Raven Software.

To mark the game's rerelease, A handful of Jedi Outcast developers (who are still at Raven working on Call of Duty games) dropped by the GDC Twitch channel to share some classic stories from developing the original 2002 game.

Here are a few select stories that writer Eric Biessman, game programmer gameplay programmer Mike Gummelt, lead designer Chris Foster and lead programmer James Monroe shared about the original game's design concepts that highlight how much game development has changed, and how the team shipped a cinematic Star Wars game with the tech they had at the time.

A more generalist age

When asked about the biggest differences between working on Jedi Outcast and their current work in game development, the team of veterans agreed that in the last 17 years, their roles in the game industry have become far more specialized, and their work on Jedi Outcast stretched far beyond their official titles.

"One of the things we talk about is back then, we wore a lot of hats," Foster explained. "I built levels, I was in charge of the design team but I also had to light levels, I was scripting, and we were doing all the continuity of everything and we were helping Eric make sure that when the dialogue went it, that it all made sense give what we had to change around."

"So we were doing tons of things. A lot of times now we’re a little more segmented. Like we build the levels and do whatever, but somebody else is doing Hollywood-level lighting and somebody is else is a scripter that has you know 20 years of experience doing it so we kind of spread a lot of those tasks out so it means a lot more communication has to happen."

Biessman pointed out that when he started at Raven, the company numbered just 13 people. Now, there's over 200. "I still love it and I love the people I work with and I get to meet a lot of cool people at different studios," he explained, "but...I would be working on the narrative, I would be working on catchphrases, I would be retexturing, I’d talk to our artists, I would help with art…"

"There was just more for you to do and I personally have not been in an editor in I don’t know how long an it’s something that you really miss."

Those generalist tendencies helped the team transition from being an exclusively first-person game developer to a third-person one. They mention that during their initial pitch to LucasArts, there had briefly been discussion that they'd be returning the Dark Forces series (which Jedi Knight technically falls in) to being a first-person shooter. But after hacking some third-person tech together, they revealed they could continue Kyle Katarn's Jedi journey he'd begun in Dark Forces II: Jedi Knight.

"There was some weirdness," Monroe admitted. "We went through a lot of weirdness to get there but the engine already had a rudimentary third-person tech, it just set the camera back and we added in a bunch of scripting and traces to manipulate the camera to make it feel more natural to do a cinematographer type thing where if you know back up into the wall it moves the camera up [instead of just clipping the camera through the wall.]"

This led to some finicky work when it came time to design the game's lightsaber combat. Dark Forces II had been a first-person game, so the team wanted to allow players to still play in first-person while designing primarily for third-person gameplay.

"The trick was I tried all sorts of different things," said Gummelt. "[I attached] the players view to the actual model, but then it was moved around too much."

"Then I tried not doing that and then your arms are moving around here while you’re back here, so I blended the two and faded out the arms. I just put some alpha from the arms so they would fade out and easily went up to the shoulders."

The weapon of a Jedi Knight

Jedi Outcast lives on in in the hearts of so many players in part because it was one of the first Star Wars games to feature deeply-designed lightsaber combat. It and its successor Jedi Knight III: Jedi Academy would feature an array of stances and specific rules about using lightsabers that still stand unique in the world of game design today.

Mike Gummelt is often credited for creating the game's lightsaber combat, but he also tipped his hat to game programmer Jeff Dischler, who developed the effects that let the lightsabers spark and leave burn burn marks on enemies and on the walls.

As Gummelt explained, "My goal was to make it so that you could be moving in any direction and attack in any direction. I worked with the animators on that and trying to keep it as freeform as possible but give you control in every direction and I wanted it to be quick, I wanted it to be responsive, I wanted it to be fairly lethal. My actual inspiration for the combat was [PlayStation 1's] Bushido Blade."

Jedi Outcast's combat also systemized one of Star Wars' most iconic moments--the way lightsabers could cut off and instantly cauterize a person's limbs, as symbolized by the shocking bar fight in A New Hope or Vader cutting off Luke's hand in The Empire Strikes Back. In Jedi Outcast, that dismemberment was made possible by the G.H.O.U.L system, tech Raven Software had developed for the Soldier of Fortune series.

The tech was so good that right before launch, it was deemed a little...too good. "I remember there were debates and rules on what you could and couldn't dismember," Gummelt recalled. Right before launch, a request came in to lower the chance of letting players cut off enemy characters' heads.

Monroe added more details. "We had to dial down the chance of dismemberment per location [on the body,]" he said. "And the neck was something like 10 percent but we had to take it down to— did we make it zero?"

"Unless it was a droid, you couldn’t," Gummelt replied.

"Right, so we had to make it actually zero. We were like ‘it’s a really low chance!’ and they said ‘no, that’s too much chance," said Monroe."

And yet a year later, Gummelt noted that those rules seemed to have changed. "Then in 2003, Episode 3 comes out and Anakin cuts off Count Dooku’s hands and his head."

"It's working! It's working!"

Jedi Outcast exists at a halfway point between Doom and Halo, with levels and shooting that feel more like the former but a visual profile closer to the latter. Short on memory and without a GPU to call on, its creators sought out unconventional solutions to deal with the technical limitations of their engine at the time.

"Radiant was our editor for the levels," Biessman recalled. "By this time at least Radiant had more than a top-down view. Because when we first started working in the Quake editor it was only top-down. You had the Z checker and that was the only way you could tell floor or anything like that and as soon as we were able to actually have multiple views it was like a Godsend. It’s a game changer."

"But really, I mean Radiant is Radiant. And at it’s core it’s building brushes, you know all of the surface things have stayed pretty solid."

Foster jumped in with the acknowledgement that "Patches have changed quite a bit from they way they have to be implemented. I mean there were never like we also had bending modes so we couldn’t just grab a point. We had a tool to take a pipe and actually bend it to a specific angle then save it and make sure it didn’t crash."

"This was before normal maps," Biessman added, "this was before specular so you know…textures were just painted."

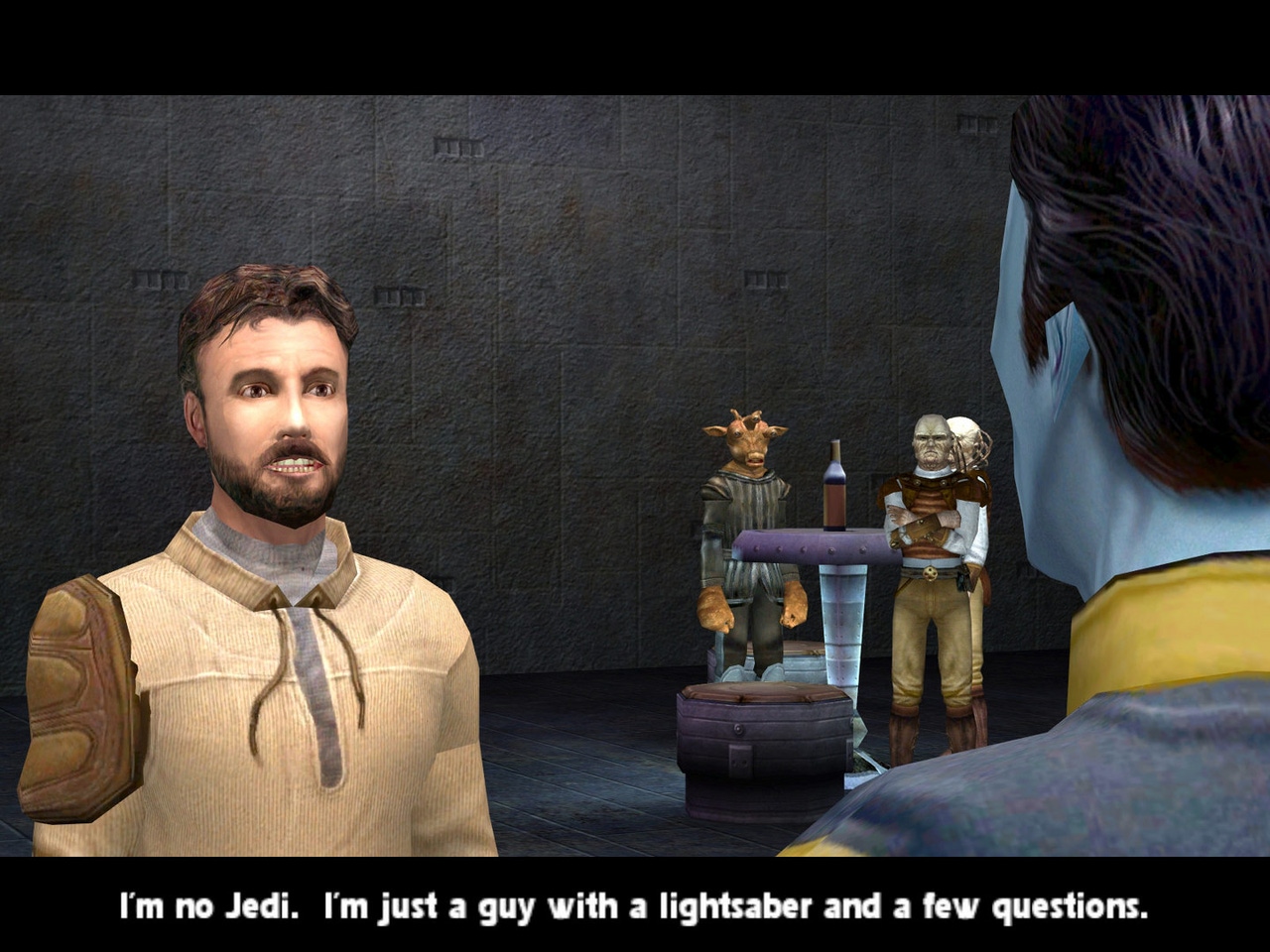

As the conversation turned toward the game's audio and animations, Gummelt recalled one particular programmatic trick that isn't likely used in Star Wars games today. "I remember I wrote a little I guess procedural kind of head bobbing as they would talk based on the volume of the dialogue," he said.

Monroe explained this meant the volume of the dialogue directly drove character animation in cutscenes. "To save memory we [didn't] store all the animations— like the upper animations are separate from the lower legs so that we could do all those left right attacks and running. The facial animations were the same way. We just stored seven phonemes you know, different mouth shapes that was to drive all the animations and then to make it seem more realistic we added some head motions so they’re not just puppets."

"We just basically made it random but as an input to the random number generator with the volume so that if they’re speaking more emphatically they had loop. And now it’s a free on the fly way to make animations."

What's striking about these stories from the making of Jedi Outcast is how many of the game's developers still work together at Raven Software. Some have moved on, but their shared workloads and overlapping experiences designing the original game emerged in their conversation about working on the game. Where one developer's memory lapsed, another stepped in to fill in the details, in part because the smaller team and timeframe meant they likely worked on those features together.

For more of those stories from the folks at Raven Software, be sure to watch the full conversation with them below.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)