Story types in the gamedev world

Game dev has redefined the concept of a story in many fascinating ways. Lets see how many different story types are out there... This article is mainly based on the information from the book “Challenges for game designers” and my personal experience.

This blog post was previously posted at http://emi.gd/blog/story-types/.

Through the ages people have been developing different kinds of stories. We try to add some excitement to our lives by laughing at comedies, crying during drama movies or screaming when a zombie suddenly shows up. Books and movies got us used to a simple type of story, when everything is settled up by the writer and the audience can only discover a concrete and static portion of action. We cannot make any changes in the plot, and these types of media are rarely reusable – nothing can surprise us in a movie that’s being watched for the second time. At first, that concept was enough also for the game industry, but the fact, that a computer program can read user’s input opened a whole new era for storytelling. Let’s see how many different types of story we can find in modern games.

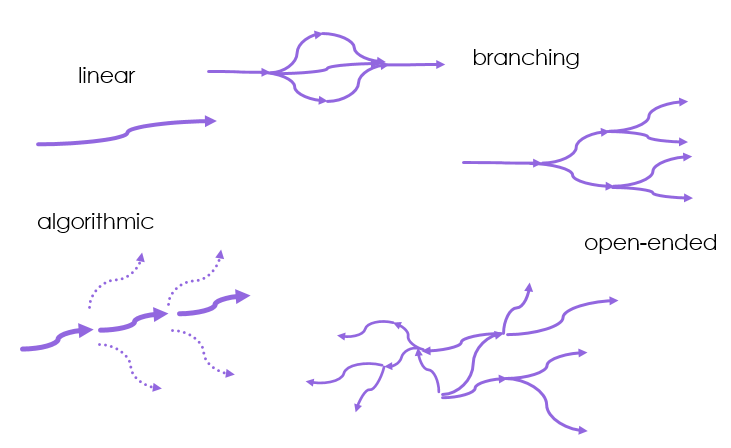

Linear stories

This is the simplest type of story that we can imagine and it has the most in common with other storytelling media such as books or movies. Player can only go straight from point A to point B, his action do not affect plot progression. The whole content that is prepared in the game will be seen by the player at his first play through, so there is not much possibility of replaying it. Games featuring this type of story are usually called as being “on rails” like a train. We can typically find it in adventure games – and some of them can be really heart-breaking, as the one in “Ori and the Blind Forest”…

Branching stories

Branching stories make use of interactive nature of games. Players can reach the end of the story on multiple ways – the path alters in reaction to decisions made by them. This really enforces the feeling of being in the center of action and is very immersive – we usually make choices as if we were the character in the game. The main disadvantage of this type of story is the cost of production – we need to create more different quests and assets than user will see during one play through. Sometimes it can be reduced by implementing a slightly modified approach – the main plot consists of general points, but there are many ways to get from one point to another. These parallel paths enhance the feeling of control, but players always end up experiencing the same ending. I think this is the most popular type of stories in RPG games such as the Witcher.

Open-Ended stories

These can be also called multilinear or threaded. There is a special starting point specified, from where the player can go in several directions. He can decide which and when he will fulfill quests, and all of his actions affect the way that the game will end. One of the greatest examples featuring this type of plot is Oblivion, which was the first game that took advantage of the Radiant AI – the system where NPCs (Non Playable Characters) can perform complex actions, which are always reasonable – they eat, go to sleep, go to work or even interact with each other in an unpredictable way. The system also alters the world and characters behavior according to player’s previous actions, for example it can spawn enemies with appropriate level of strength at places that have not yet been visited. All this effort is to maximize the feeling of genuineness of the game’s world and cause every play through to be different. Obviously, this type of story involves the biggest costs and caution – the plot has to make sense irrespectively of an order of quests completion. This is probably why this type of games usually have dedicated teams of writers and are created by the biggest studios - like the GTA for example.

Algorithmic stories

For me, personally, this one is the most intriguing, because it feels like the AI really behaves on itself. This innovative approach implies story generation that is performed by the computer system. A story writer defines nodes, that have starting and ending points defined, along with a set of requirements that have to be met for the node to be included as part of the story. The AI reacts on player’s actions and alters the plot direction by choosing different story nodes. Between the nodes a player experiences an open-ended type of story. This allows us to have fully parallel, different paths for the player to take, without the need of having to define every full branch separately. This sounds great, but this story type is kind of experimental. For example, a nice game that uses this kind of mechanic is Façade – its creation took five years and it provides only ~20 minutes of gameplay. If you haven’t heard about it yet, don’t hesitate to check it out right now – you can download it for free. It’s a really fascinating piece of game art. And if you’ll manage to achieve a happy ending, let me know how you did that. ; )

So this is how I imagine a graph-like representation of the above types of stories:

The book also defines other types such as instances – kind of mini stories that don’t really affect an overall outcome of the game, mostly found in MMO games, emergent stories that are created purely by players that make use of an in-game mechanics (The Sims) or even thematic setups, that are barely opening cut scenes that put us in the right mood.

The most fascinating thing is that there is no “best” type of story – it has to be chosen carefully with full understanding of the nature of story that we want to tell and the type of game that we are creating.

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like