Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Indie Fund Shadow Physics developer Steve Swink discusses creative inspiration, the realities of developing games in a fiscally-driven world, and how Braid and Portal profoundly influenced his conception and understanding of development.

[Indie Fund Shadow Physics developer Steve Swink discusses creative inspiration, the realities of developing games in a fiscally-driven world, and how Braid and Portal profoundly influenced his conception and understanding of development.]

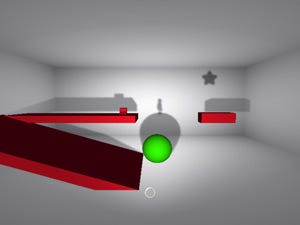

As a veteran indie game developer -- in the current sense of the term -- Steve Swink is making the biggest bet of his career on Shadow Physics. The downloadable game, currently under development by Swink and Scott Anderson, was announced to be one of the Indie Fund titles at GDC. It's targeting the Braid space -- creatively and in terms of its audience.

Swink is a big believer in the experimental gameplay methodology, an approach he's both taking with this title and which he also outlined passionately during a well-received talk at last year's GDC China.

In this wide-ranging interview, Swink talks about the games that cast their shadows on his own creative process, how different developers tackle development -- what works and what does not -- and how going back and examining previous games to understand how they work is essential to progressing the medium.

The reaction you can get from the public makes the act of creation daunting, doesn't it?

Steve Swink: I don't know if it's because games are so new, but I find that everyone thinks they know how to design games. Even more than people who think they know how to make movies, or think they know how to write books.

I'd say that it goes that way: it's like games, movies, books. Like people have ideas for screenplays, before they have ideas for novels, and so on down the line. Maybe it's just the age of the medium, you feel like there's not as much ground covered, so maybe your unique voice would carry you through -- even if you don't have the craft or talent. Or something.

I don't like to make sweeping generalizations, because I feel like nobody actually knows how to design a game. And I feel like if you talk to people who I think are the best game designers in the world, even they will tell you that they have no idea how to design a game really, and they just have some data points, and they feel like they got really lucky with being at the right time in the right place.

I don't know; it's sort of weird. It's like everyone judges games monetarily, in a lot of ways. Because that's the one bottom line of success that no one can argue with; it's like the "take it home to your mom" kind of success. You can prove to your dad that you're worth a damn if your game made a bunch of money, kind of thing.

But I don't think that's necessarily good or positive. Like I think Cactus's games, and Messhof's games, and weird things like Increpare's games, some of those have a lot more interesting things than most mainstream games and most indie games, and they get overlooked because they never really made any money.

Shadow Physics

When it comes to indie games, it's something of a chicken and egg thing. They get overlooked because no one's out there shouting about them. Who's really shouting about games? Usually it's marketing people. Even with indie games to an extent, especially if you end up in XBLA or something, right?

SS: I think we, in the indie scene especially, are very myopic in the sense that we know all the games that are coming out, we have our finger on the pulse, and we are even at the point where we're starting to think certain types of games are tired, and all that sort of thing.

But what we always forget is that even games that we consider massive breakout hits -- like your Minecraft, the Braids and the World of Goos and even Portal to some extent -- are not part of the broader conversation about video games.

The broader conversation about video games is a sound bite on Fox News about Modern Warfare 2 coming out; that's the way that the general public digests games. And so they've never heard of Minecraft except as a story about a game that made $10 million being sold through a website, through no portals, and no consoles. And in some way it becomes self-reinforcing, because that kind of press is really fascinating to a lot of people.

It's like, wait a minute! You play Modern Warfare, you play a lot of PC games maybe, you hear about this indie game that has made $10 million just from the website, you're like "What is this?!" And it sort of balloons up in these little viral clouds wherever one person tries it, it's like, "Oh!", and then all their friends buy it, too.

But I think in a lot of ways, what's driving the publicity of that is the story about how much money it's made once it's crossed a certain threshold. I mean obviously, it has a lot of things about it that are really interesting, and cause it to be shared that way.

Well, one reason is it takes a lot of time to make games, and if you are going to do it -- fully committed to it -- you need money to live, because that's how our society works.

SS: Right. But I mean I think you need a lot less money to live than a lot of people think. It just depends on how you…

Want to live?

SS: Right. The standard of living to what you have become accustomed to, I guess. So right now, I'm basically living like a college student. I don't buy anything except for food and travel, and I try to cook food for myself because it's cheaper, and my big expenditure is, like, having a guy come clean my pool so I don't have to do that. [laughs]

You moved to Phoenix [Arizona].

SS: Right, and we moved to Phoenix, which is an awful cultural backwater in some ways.

But it's a lot cheaper than staying in Sunnyvale [California], which is where you were.

SS: Right. It's less than half. My four bedroom house -- which I probably should have not purchased, but did in a fit of, "Oh, it's really cheap to buy houses!" It's like a thousand dollars, and I have friends who live there -- indie developers -- and they don't really pay rent, and it doesn't really matter because it's so cheap.

I've been thinking about this, and also Ron Carmel's MIGS keynote. Part of it was about how he'd like to see the major publishers create pure R&D groups, where they put aside like 10 or 20 people and have them just like go do crazy stuff and make stuff.

Similar to how right now Microsoft does pure R&D, and then potentially those things could filter into commercial products. I think that makes more sense.

SS: Well, I think if you look at the story of the last 10 years of video games as a medium, the big story is Nintendo and the success of the Wii. Like, if you look at the last 10 years of game sales, nothing has sold anywhere close to any of those Wii Sports titles and all that stuff; Nintendo is just printing money with that thing.

And that was the result of Nintendo R&D going crazy, making weird crap. They made the Wii. Who would've thought that would've worked? Some people did, and some people didn't. Nintendo has a history of amusing and costly failures, but when they hit they hit big, so clearly their R&D pays off.

But I also think Nintendo is really smart... I don't know if Miyamoto understands this, although I suspect somebody at Nintendo understands that games are comprised of software and hardware. And so when they create games, they create hardware simultaneously, and those two things are not viewed as separate -- they're viewed as parallel developments.

Because the tactile sensations from the controllers feed into the way the game plays and the way people experience it, it's all a sort of holistic product design. I think parts of Microsoft have caught onto that a little bit, and the reason I think that is the Xbox 360 controller has become the de facto standard for PC development -- if you're going to make a game on PC that uses the controller.

And it's because it feels so good, you know, it has a wonderful tactile sensation; the only thing that sucks about it is the D-pad. Everything else about it is like the best standard controller that's ever been made. I don't think a lot of people would disagree with that, because what are the other contenders? There aren't any.

It's really easy to understand why the Microsoft 360 controller is like really, really good. The springs feel really good, the surface of it is almost like smooth human skin; it's sort of creepy if you think about it.

Well, it's creepy if you put it like that.

SS: No, no! What other texture is it similar to? Like if you feel it, you're like, "Why does that feel so good?" And the buttons press down in this very particular springiness that's extremely satisfying.

A lot of my friends will tell you this too, I think. But if you develop a game, and you like make it in Unity or something, and you play with a keyboard it feels a certain way. And then if you plug in an Xbox 360 controller and hook up the controls, it immediately feels really good. It's sort of like cheating.

But Nintendo's got their finger on that; they understand that the tactile feel of the controller is part of the experience, like a really, really important integral part of it, because they develop both at the same time.

At GDC China, you talked about Mario 64. Someone asked when the last time you played Mario 64 was, and you said it was like six months before.

SS: Yeah.

Why?

SS: I kind of feel like we need more people studying games, and I don't see a lot of people doing it. I don't return to games like that purely for joy, but I return to games that I really enjoyed that I think still have something interesting to teach me, because I feel like I've missed something, I guess.

And there's a certain type of enjoyment you can get from playing a game that way -- where you just really deconstruct all the mechanics and stuff. But Mario 64 is one of those games that just did a lot of things really right for me, and the way I like to play games. And it's hard to make generalizations like that, because there are a lot of potential experiences you could have playing Mario 64, and you have to have a certain level of adeptness at playing platformer games, I think, to really get all the super awesome benefits.

But there are just some really great design decisions in there, and a lot of things I felt they missed in Mario Galaxy. Like Mario Galaxy was supposed to be this big return to form after Mario Sunshine, which people did not regard as that great of a Mario game. But I just really miss that sensation of open exploration.

Like I felt like Mario Galaxy was a series of challenges in Mario style, but missed what fundamentally attracted me to Mario 64. Which was like... you could stand in the middle of a field and stare at a giant mountaintop and then find your way up there, and there was sort of an interesting process of exploration.

And it wasn't so overtly challenging, like I think by pitting you directly against challenges designed to make the mechanic hard -- at a certain ramp, obviously linearly -- but I think that defeated much of what was beautiful about Mario 64, and to a lesser degree, Mario Sunshine.

What other games have you studied this way?

SS: You know I've played through Braid, I don't know, like 10 times or something, and the same with Portal. And when I play those games, I look at them -- well, at least I like to think I look at them -- in the way that a composer looks at a piece of really good music. And I think I see some things that you don't see unless you're trying to make a game like that, and when you play those games there are just hundreds of little tiny design decisions and that's a very different way to play a game.

But when I play games that I think are really good, that have a really wonderful progression, and they exploit really fascinating mechanics in an interesting way, and it's all just put together extremely well -- like the holistic view has been observed and understood, and everything fits very well and it's very clean and elegant and beautiful -- I get really inspired.

I mean I play through Portal and Braid and World of Goo and X-Com and stuff, and I get ideas for Shadow Physics levels really quickly. And it's not based on the surface similarities, it's based on...

Like that level in Braid where there are three piranha plants and you have to rewind to get them at the same period of amplitude, and so you have to like adjust them so that the little goomba guy gets through at the right time.

And I'm not imagining it three shadow plants and a shadow goomba wandering through there, or that sort of thing, but it just really fires off my idea bone; it doesn't feel like play, it feels like study. But a really fruitful study, it feels really interesting.

Talking about analysis and inspiration, how does that filter into Shadow Physics?

SS: Yeah, well, it's like the purpose is to make something, hopefully, that can be really interesting and beautiful and make somebody's life better. I think the highest piece of praise you can give to a painting, song, movie, game, is that it inspires you to create. If you make something that inspires kids to want to be game designers, that's the highest possible praise you can ever give to someone.

That's sort of like the litmus test. That's like a symptom of making something that's that good. And I still feel like we lack the language in order to describe what's good about games like that, and why they're so good.

And so when I play a game that I think is that good, I'm always just trying to gather all this data together to form some picture so I can understand better and try to articulate why it works the way it does.

And part of that is the process behind making it, and part of it is the result of making it, and part of it is which design decisions were important and which ones weren't, and, you know, part of it is luck or whatever. But that's sort of like the whole thing coming together -- it's that desire to make something beautiful before my hours are up; to make something that is meaningful.

And so ultimately, I think that should be the metric by which we judge whether or not a game is really good -- not how much money it makes. You know, by how many people's lives it touches, which is an impossible thing to measure. But there are artifacts that you can look for. It's like you play a piece of Mozart music, it's really hard to argue that that is really beautiful piece of music. It's like the Aria of The Queen of the Night from The Magic Flute; it's like a cellphone ring tone, you hear it all the time.

Talking about the money question -- money equaling success -- obviously Braid is an objective success, if that's how you define success. But at the same time, you can also take Braid or Portal and you can move back and think about them in terms of, what games did you hear people actually bothering to talk about for more than the first six months after they were released?

SS: Yep. Yeah, what were the formative games of the last ten years? The list is very short. I feel like you can tell the difference when someone's talking about a game that just did really well and made a bunch of money, or is successful in the way that games have been successful for many years.

Like StarCraft II. A lot of people love that game, and I feel like I have a handle on why a lot of people love that game. It's because they had enough money to spend on it that they can spend as much time as it took to make it just an immaculately balanced game.

But that's different from the reason why people talk about Braid and Portal, because Braid and Portal are different, but they're different in a way that is really, clearly wonderful and interesting to people. It's kind of like Passage, because it's really hard to define what it is about that and how it all comes together. I think even Jason [Rohrer] is struggling just a little bit. It's like, I don't think he's been able to recreate that type of resonance in any of his other games.

Nobody really talked about Sleep is Death. I mean, it seriously lasted like 10 minutes on Twitter. That's a cynical way of putting it, I guess, but...

SS: No, no. And that's fair. I think a lot of people gave it a chance and did not find in it what some people did. Here's a perfect example, and this I have no explanation for -- well, I have an explanation for it, but I think it's really sad. Did you ever play Captain Forever?

That was just a wonderful game. I feel like it's a game that was made for game designers, though. Because my favorite part of the game is tuning the feel of a system, and that was like a lot of what the game was about.

So many people didn't get that. And I just thought that game was going to take off like a rocket because I had so much fun playing the game; I played so many hours of it. Its accessibility is the problem with it.

That was one of the really sticky innovations about Portal: the Valve method of like just playtesting the fuck out of it and realizing, "Hey, we are asking too much of people in this level. We're asking people to do too many things to solve one level. Let's take those two things that we thought, 'Oh, anybody could do that,' and separate them into two levels."

The thing is, while that sounds like it's kind of condescending, A) nobody knows because when you play Portal you certainly don't know what the developers were thinking. And B) no one's dissatisfied -- no one's sitting and playing Portal thinking, "Man, this game is talking down to me because I had to solve two puzzles in two levels."

SS: Well, there are two really important lessons there. One is depth first, accessibility later -- which is kind of one thing that we're struggling with on Shadow Physics right now. It's like we had these levels, that were a bunch of interesting expressions of shadow mechanics, and then people would play it, and then not be able to figure it out.

And so I went and made the game really accessible, but then Jon [Blow] made a really good point to me, which was that if you're going to tutorialize something, you have to show people why it's awesome right away; it has to be magical as well as teaching.

And so I went and made the game really accessible, but then Jon [Blow] made a really good point to me, which was that if you're going to tutorialize something, you have to show people why it's awesome right away; it has to be magical as well as teaching.

It can't be "Here's a bunch of stuff, and you just have to trust me that it'll get cool later," and that was the problem with Captain Forever. I was telling people this literally aloud -- like, "You gotta trust me; you gotta play this game for enough time so that you understand what's going on." And not that many people did.

But also Portal and Braid have a fundamental advantage over something like Captain Forever, which has more of a conceptual underpinning. Although it is really fun, it feels really good to drag your pieces around and arrange them.

But [with those games] it's really obvious immediately what the innovative, interesting thing is; it's like you just hold down a button and time rewinds as much as you want, or you shoot a portal at a wall and at another wall. What is cool about it is obvious; the ramifications of that are not necessarily obvious.

But now we're back to really pushing for depth in the Shadow Physics mechanics, and as I said earlier, that turns out to be a really hard thing to do. Because you are a shadow; you don't do a shadow, it's not a verb inherently. It's you are a shadow, then you run and jump and push and pull and slide and break things and...

You do what Mario or Lara Croft does, but as a shadow.

SS: Right, and so it's like a riff on all these different mechanics. And so the interesting question is, can we find depth that we need? And obviously I think we can, and a lot of other people think we can too, but that's part of what I meant about letting the game go where it wants to go.

So we have this experimental methodology in mind where we're going to take the time to explore the mechanics as deeply as possible. But by its very nature, because you are a shadow, it's not about a very specific aspect of fiddling with shadows. It may be a more compartmentalized or diffused experience, where it gets deep in a bunch of different areas, or it gets a little bit deep in a bunch of different areas. The thing that ties it together is that you're a shadow. It's a really hard problem.

With Portal or Braid specifically, the other thing that makes it really obvious with what's cool about them is everything else about them is normal. What I'm trying to say is…

SS: They were grounded in familiarity.

Yeah, exactly.

SS: They only innovated in one dimension.

You're completely familiar. You can contrast Portal against Half-Life 2 very easily to see what's different about it. And with Braid, it's the not-so-subtle nod to Mario all the time.

SS: Well, I think that that is part of the strategy that you use as a designer to get people into the game. You drop them off in a familiar context -- it's a first person shooter, it's a platformer -- and then you can let them feel grounded, and then you ease them into the weird, crazy stuff that you're going to throw at them.

You've put like a year into the game so far. How much more time are you expecting to put into it?

SS: Another year and a half or something. I don't even know, really.

So now we've got sort of a general idea of how long these things take to make. The sort of thing you're trying to make, which fits in a certain constraint -- which is a downloadable game that's worth 15 dollars to a lot of people, approximately.

SS: A fair number of people.

That's what I'm saying you're making; the thing you've made has sort of been quantified by the circumstances that you exist in.

SS: Yeah. Certainly ten years ago I would not have been able to find funding, nor would I have been thinking about making a game like this.

When Jon first showed Braid at the Experimental Gameplay Workshop in 2004 or whenever it was, I was like, "Yeah, alright. Well that's it, that's the kind of thing that I want to be making." And it took him another three years or whatever it was to finish the game to his satisfaction and put it out.

And then when he put it out there wasn't necessarily that expectation that that was a viable way to go.

SS: I said to [GDC's] Jamil [Moledina], Meggan [Scavio], and Simon [Carless] before Braid came out, "If there's any justice in the world, Braid will be like the first big indie breakout hit." And I was really happy. Because in my mind, that vindicated my internal conception of quality, in some ways. Like I look at that, and that's exactly the kind of game that I'd want to have designed, and I think it's really an example of really excellent craft married with a great artistic idea.

It's philosophically sound, and constructed in a way... it's like a really gorgeously crafted pot. If you find that from a society, if you're digging around in the ruins of some society and you find this immaculately crafted piece of clay or whatever it is, you know that they had the technology to do that, and it was up to a certain standard. It kind of feels like that -- it's like an artifact of how far people have progressed in a certain direction, which is sort of a weird thing to say.

If you prove to me that you can make a game that is beautiful and contemplative and not about explosions or tits, and people will dig it and some people will get the message and some people won't...

And it's like the opposite of quality is apathy, not hatred. And there are just tons of people out there who just bagged on the story of Braid, and played the demo, and thought it was just a stupid platformer about time rewinding, and didn't get to any of the deeper messages. And a lot of people thought that it was pompous and pretentious and reacted against that and so on. But it just proved to me that it's possible. You can do that.

So you've done a lot of indie experimentation and then you sort of realized like, "Okay, this is what's feasible. Let's spend this much time on a game." You have a certain ethos you talk about, like not wanting to repeat content. You have a picture in your head of the space you can operate in right now.

SS: Yeah, there are a lot of self-applied constraints in this type of design.

That's a rising part of the medium right now.

SS: Yeah. In the past, that sort of constraint has been applied by hardware. Like there's a lot of really interesting Atari games that were really weird, that have no successor in modern games, that maybe we should go back and look at, because they were really interesting and they arose out of the constraints of the medium. Or maybe the limitation is gone now, and something more interesting will come out of it.

SS: Yeah. In the past, that sort of constraint has been applied by hardware. Like there's a lot of really interesting Atari games that were really weird, that have no successor in modern games, that maybe we should go back and look at, because they were really interesting and they arose out of the constraints of the medium. Or maybe the limitation is gone now, and something more interesting will come out of it.

You know, Chris Crawford looked at that, and he saw people, not things. It'd be great if there were a 100 more people mining through early weird Commodore games, looking for stuff that just hasn't really been followed up on. Because people didn't know any better, so they would do crazy shit and they'd fail spectacularly. I feel like a lot of people are afraid to fail spectacularly now.

Well, you can't.

SS: Jason Rohrer's not.

Well, Jason Rohrer… he's awesome, but he's an extreme example of how someone is willing to live their life for the capacity to fail as much as they want, and do whatever they want. You say you live like a college student, but he lives like Jason Rohrer. There's no comparison.

SS: Yeah, exactly. It took until now to muster up the courage to make Shadow Physics a full time profession. And it is really, really stressful at some fundamental core level, because if the game turns out to be total crap, then you know I've wasted my time.

I feel like I'm learning a lot on the job. I feel like... there's so many things that I just haven't even thought of, and I'm learning so much as I'm going along, that hopefully the quality will be what I want it to be.

And I think that's part of why I take so long to make a game like this, because you have to have shower time, you have to be thinking about this stuff while you're taking a shower, riding a bike, doing stuff that's totally unrelated, and you just have these insights that pop into your brain, that come from that weird dimension of creativity that no one understands -- but people who make stuff know it exists.

It's recognized. I've heard people talking about this even from a business perspective, where they have to let people get the fuck away from work and just, when they're on their own time, they'll pop out an idea. And everyone who's ever done any creative work talks about, like, getting out of bed and jotting something down.

SS: Yeah. So it's really, there are two things there that are really at odds. One is the need to do that, and just kind of dick around and live your life and do things. Like go hiking, and running, and whatever.

But then also you get funded, or you have a certain amount of money that's burning down in your bank account, and you need to get something out by that time. It's like there's this sort of two... it's typical. So Ithink most really successful artists are people who can produce on a schedule, whether it's self-imposed, imposed by money, or imposed by an external group or person -- but are also able to not sacrifice quality to do that.

And I feel like I'm only now beginning to understand the parameters in which I'm working, with the ramifications of the constraints that I'm applying to what our design is. And it's not at all clear how to thrive within those parameters.

When you're making Tony Hawk -- and I'm just using this example because you worked on it -- you need a certain amount content, but it's also well defined what that content's going to be, so you just sort of set people about generating it, right?

Whereas with you, you're talking about the fact that you only want to generate enriching things. And you're experimenting a lot, so I'm sure you throw away experiments.

SS: We throw away more than we keep.

And you don't want to keep things that are just there to fill time for the gamer, right? You'll end up with a game that's more...

SS: Cohesive and tight, one way to describe it.

It's very different than commercial game design.

SS: It's sort of fundamentally opposite to the idea that a game should take a certain number of hours to finish, and its inherent value to the consumer is based on how many hours it takes to finish, as opposed to the quality of those hours.

I mean I'd rather play a game that takes five minutes, like Passage, that I find really thought provoking, interesting and memorable, than I would want to play a 200 hour JRPG where I didn't find any of those things true.

Though it's also, I think, a cultural question in a sort of a broad level. America is the culture of bigger, better, all-you-can-eat. I mean, how much would anyone think Passage is worth?

SS: I don't even think you can apply that kind of value judgment to it in a lot of ways. And I think that's a reason why a lot of people are attracted to it, because it's like, "What is this? I can't put it into a bucket that I already have, so how do I cope with that?"

And it's not a product -- he later sold it for iPhone for a dollar or something to have money to live or whatever -- but it's not inherently a product and it wasn't created to be a product, obviously. It was created as an expression, so how do you make a product that also retains that beautiful creativity?

Well, maybe you can't.

SS: So Braid's proved that you can, I think.

Some of the artistic payload of Braid, I think, is of lesser quality than the mechanic exploration and brilliant puzzle solving. Although that was kind of part of the payload, too.

It's literately impossible to make a living writing poetry in America right now. No one does it.

SS: I never thought of that.

If you know poets or you read about poetry, you have to teach -- essentially have to be an academic -- and write poetry in your own time. And it does feed into your academic career, but it's indirect.

SS: Isn't there still like an American poet laureate or whatever, or someone holds that position as being the poet of America?

That's one person.

SS: So it's not like people are living off of being poets.

I have a friend who's a poet and she is also an optometrist.

SS: Ha! That's awesome.

It is awesome, but... I guess the analogy I was making is that Passage is a poem.

SS: Yeah, I guess that's true. I'm obsessed with movie trailers, because so many movie trailers are so much better than so many movies. And I find it really fascinating that it's so much easier to strike emotional chords in a movie trailer -- or so it seems -- to give you that sort of choked up feeling or that visceral feeling in a very short form than it is to make a really great movie that sustains itself all the way through.

But I feel like if you watch Apocalypse Now and you get done with it, that's a lot better than watching the trailer for Apocalypse Now, where you never get the same depth and quality and feeling. So it's sort of like what do you want to go for? And that's the answer to why you would try to make a larger form -- although still shorter than most games, indie games -- there's a greater possible depth there.

And it's like the difference between Passage and Braid or whatever, although those two don't compare that well, because they're very different; but you sort of see what I'm saying. That's the point of exploring the mechanic really deeply -- it's like you mine deeply enough that you find that, but context is so important, too. It's like you have to have all these other things leading up to it and you have to be controlling what the player is focusing on and what they're thinking about in a very intelligent way to give them that experience, to build up to that experience.

The guys who made Portal thought a lot about what people were learning when, but also what GLaDOS was saying and doing, relative to what people were learning when. And that's how they kept it from getting really tedious, so they just kept throwing new mechanics at you. Now all of a sudden you're pushing back against GLaDOS and getting free of the test chamber and so on.

Yeah, the moment in Portal where you get out of the test chamber and go in the back of the compound is perhaps the coolest thing that happened in a game this generation that I played.

SS: Yeah, totally. And what's amusing about that is that it's sort of a narrative thing. In the Source engine, it's the changing of some wall textures and placement of objects, right? It's not anything to do with the novel mechanics but it was they decided that that particular point they watched a bazillion people play through it, they decided at that point people were starting to get really bored of the mechanics and learning the mechanics -- "Okay, we're gonna let them break free" -- and now you're pressing against this antagonist.

And that is what motivates your action for the rest of the game. I don't know, just brilliant the way it all fits together.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like