So what about the men?: A deeper look at Firewatch and Catherine

What would more compelling, more human male characters look like? Atlus’ Catherine and Campo Santo’s Firewatch provide elements of an answer.

The representation of male characters in videogames leaves much to be desired, certainly, but any mention of this is, often, little more than a foil to be used against women arguing for better female characters. Indeed, concern about male characters is usually nothing more than a rejoinder to people who talk about women in games; we never get much further than that in the discussion.

But what would more compelling, more human male characters look like? Atlus’ Catherine and Campo Santo’s Firewatch provide elements of an answer.

One can never escape the specter of sexism, or of male fantasy fitting uncomfortably over the actions of the player, but these games nevertheless humanize men in a way few videogames do, presenting them as vulnerable and flawed people that have much more in common with the average man than, say, Marcus Fenix.

***

Catherine is an interesting case as its gender politics is something of an especially confused trainwreck. No less a figure than The Escapist’s Ben “Yahtzee” Croshaw argued that the game was “misogynistic” for its nigh-on Freudian portrayal of women as an all-consuming and nightmarish force in men’s lives.

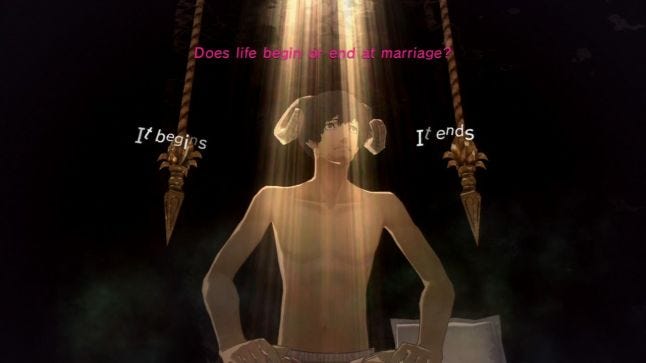

Much of the gameplay consists of the protagonist, Vincent, solving various climbing puzzles. Each represents an existential nightmare where he must reach the top of a tower of blocks and escape lest he be devoured by the feminine horrors that stalk him. If he fails, he dies. This plague of nightmares begins to afflict every man in the game’s unnamed city; life-or-death struggles to escape their worst fears.

Vincent in particular is stalked by everything from his girlfriend Katherine in a wedding dress, to an anthropomorphized female derriere, to a gigantic baby (can you tell he has ‘commitment issues’?)

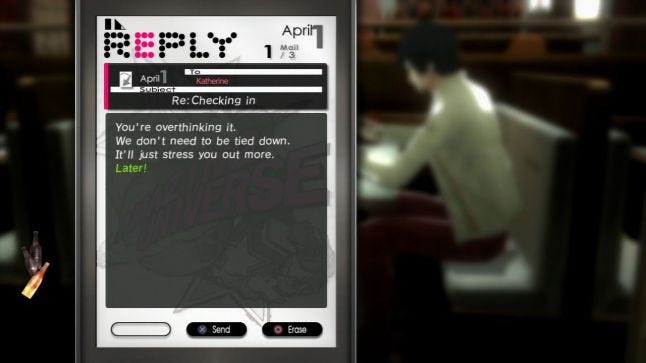

In his waking life, Vincent is torn between his demanding, successful and mature girlfriend Katherine (full disclosure: my name is also Katherine), and a mysterious, seductive young woman named Catherine, who promises freedom from responsibility amidst sensual indulgence.

Each woman serves less as a character than an abstraction with a face, Katherine is the maternal nag that threatens to consume all male autonomy, Catherine is the sexy ideal who promises eternal fun. In this way, each of these women is no less a symbol than the Oedipal nightmares that chase Vincent in his dreams. They are the polestars of a particular male universe.

The whole affair made me roll my eyes more than once, of course. But even if I can agree that the game is most certainly misogynist in its portrayal of women as ciphers for male fears, it nevertheless serves as an interesting (and relatively unique, among videogames) exploration of modern masculinity. Vincent is, after all, not a typical videogame protagonist; he’s a physically weak, somewhat shiftless young man with a low-level tech job. It’s hard not to imagine him spending his downtime on Reddit while he’s at work.

He’s exactly the sort of character many videogame studio executives would pitch Marcus Fenix to as an escapist fantasy, but of whom they’d rarely tell a story of his own. As an elaboration of male nightmares, the game is absolutely fascinating.

Game mechanics, when their potential is truly unleashed, tell a story all on their own, with each button press a syllable in the larger grammar of it all. Atlus does a stunningly good job of making the breathlessness of modern men’s anxiety into a game. The exhausting timed block-tower puzzles that dominate the game serve as a perfect ludic metaphor for the way all too many young men these days approach women in society: viewing them as an all consuming terror, each new dawn bringing one more grasp of precious life where they are still their “own man.”

As Croshaw also pointed out in his video review, this is a somewhat reductive and prejudicial view of men, and I can’t entirely disagree. Not all men think like this (as I’m sure some commenters have already told me down below before reading this paragraph) and Vincent is as much a one-dimensional stereotype as Duke Nukem in some ways.

But what was fascinating about Catherine was how it nevertheless surfaced something most games bury: gender politics, with all its grotesqueries.

In telling its particular story, this game managed to show Vincent as a vulnerable man struggling against his fears--which often took the shape of a woman. The game is not as critical of this as it could have been, but in the process it tells a relatable story that marks the game as a signature text of masculinity in our time.It provides a roadmap for considering how we might begin to tell men’s stories in a more compelling way.

And Campo Santo’s breakout hit Firewatch manages to do this without most of Catherine’s sexist baggage.

***

Early on in the game, Henry--the character you play--is tasked with scaring away some litterbug campers who also think setting fireworks off in a national park is a terrific idea. The two young women, predictably, take exception to Henry doing his job and among other things call him “a sad man out in the woods.”

There’s some truth to that cutting insult, however. The game is clearly framed as an escape from Henry’s responsibilities; as his life falls apart and his wife Julia slips away into early onset dementia at 41, he fades from the life they had built together and retreats into the woodlands of Wyoming to work for the National Park Service as a lookout.

The game isn’t uncritical of this. Delilah, Henry’s boss who at times acts as his flawed conscience, clearly disapproves of leaving Julia in the lurch. But Henry still comes off as a good man, if a bit understandably listless.

The game is about how he finds some part of himself amidst the isolated travails of this fictional National Park. Even if he doesn’t know where he’s going for most of the game, you still see the broad strokes of who Henry is; a funny man who loves dad jokes and is something of a terrible flirt.

He takes to the outdoors quickly and, although he hardly cuts the figure of Charles Atlas, he’s a fit enough man to climb over the game’s various rock outcroppings. He seems like a fairly ordinary fellow, in other words. He’s not quite the nerd stereotype that Catherine’s Vincent is, either.

You get the sense that he’s not easily led by his other head and he doesn’t have infantile fears of women’s agency--the commitment he does struggle with, to his terminally-ill wife, is one that is more fully explored without recourse to stereotypes about men. You as the player are made to empathize with his choice, even if it feels morally noxious at times; you explore Henry’s need to run and escape, and it’s not ground in his manhood as much as it is in his flawed humanity.

Even so, this is a game that is indisputably about men and masculinities. The subplots and letters sprinkled throughout the park tell the stories of various men and boys, the tragic tale of father and son Ned and Brian being paramount among them. Ned, an ex-Marine and committed outdoorsman, was one of Henry’s predecessors in the Two Forks tower and, against regulations, brought his son out to the National Park during his stint there. The reason he did this was, in no small measure, to “toughen up” the boy and wean him away from his nerdy, sedentary hobbies like roleplaying games. Brian actually hides his father’s climbing equipment so he can say he lost it and thus avoid the climbing lessons he so hated; it’s a remarkable glimpse into the coping strategies of clever children dealing with abusive parents. When you can’t say “no,” under pain of a disciplinary hand or belt, you find a way to take care of yourself.

I had hoped that this game would have a Gone Home-style fakeout when suspicion began to rise that Brian, who had gone missing years ago, was in fact dead. But it was not to be. You find his body, still wearing a Wizards & Wyverns t-shirt, in a cave at the foot of a failed spelunking attempt. His father, pushing him so hard to be more like him, ultimately killed him. The entire thing is a parable of toxic masculinity--instead of accepting his son as he was, Ned dragged him into the wilderness to make him into something he wasn’t, and ended up sacrificing him on an altar to “real manhood.”

It’s a terrible and timely reminder of the hidden cost that comes with our most cherished myths about masculinity.

Henry himself can also be read as a male fantasy, as was argued in this brilliant reflection by the blogger Sleeping Zebra, a man who can more or less completely control the world around him and has perfect control over interactions with the one woman in his life, to whom he can appear limitlessly funny or taciturn and condescending.

But, as Zebra also notes, this is a story about a loss of that control, and how one man and one woman respond to that. It’s that vulnerability that marks the difference between a classic masculine myth story and a tale about an actual human being who happens to be a man-- or a boy, in the case of poor young Brian.

If nothing else, stories such as his deserve to be told more often.

Katherine Cross is a Ph.D student in sociology who researches anti-social behavior online, and a gaming critic whose work has appeared in numerous publications.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)