Road to the IGF: 11Bit studios' This War of Mine

11Bit Studios' This War of Mine stole hearts this year thanks to its gripping, civilian-focused twist on the wartime setting. Now it's up for the grand prize at the IGF -- we catch up with the team.

11Bit studios' This War of Mine captured hearts this year thanks to its gripping twist on the wartime setting. Instead of playing as soldiers, players manage civilians under siege as they build, scavenge and collaborate. It's the game's small details -- elements of random generation, or the personal, genuine feel of each character -- that make the experience so riveting.

It's now up for an Excellence in Narrative award at this year's Independent Game Festival, as well as for the Seumas McNally Grand Prize. We caught up with the Polish studio's art director Przemek Marszal and design director Michal Drozdowski for our Road to the IGF series of interviews with nominees.

What's your background in game development, and what inspired you to create This War of Mine?

Michal: I started making games back at the university -- they were small projects developed in a time where the PC was referred to as the "386." Then, I was taking things step by step in different companies, learning how to be a game designer and project lead. Eventually, I joined Metropolis Software. It was there that I met the people I've been working with ever since. Some five years ago we decided to start a new company with a very creative approach to making games, and this is how we started 11Bit studios.

The inspiration to create a game that would address the fate of civilians in times of war came from Grzegorz Miechowski, CEO at 11Bit Studios. At some meeting he brought up that idea, and it suddenly became obvious that everyone wanted to create it. Digging into the subject further was a very inspiring experience; we based our research on different conflicts, including the experiences of Poles in the Second World War.

Przemek: Back during my C64 days, i started playing with ASCII graphics. Then came the “computer scene” – you know – demos, intros, competitions. It was one of the creative outlets for computer expression before the internet days. And after some time came our first commercial game – Starmageddon / Project Earth. It was an evolution from one of our technical demos that we'd made just for fun. After that, it started to become my favorite hobby, as well as the best job I ever had. We met with Greg, Bartek and Michal at Metropolis Software, made a few games, and started a new company, 11Bit studios.

This War of Mine

As for the game's inspiration - I will tell you from the visual side. From the first minutes in which we started working on art direction for This War of Mine, we knew that it must correspond with our game theme. And we knew that doing it in a super realistic way was not an option. Our game is like a novel, and we wanted to have this novel feel on the visual side, too. There were two main sources that inspired us the most. One was music videos from the 80s and 90s. Experiments with hand drawn cels over movie footage, etc. And after some research, I think we succeeded in achieving this time-lapse pencil-like sketch. The second area of inspiration was mostly connected with our work toward color and mood. And this time works of Banksy appealed to us the most.

What tools did you use?

Michal: We use in-house tools. We have our own engine called “Liquid Engine,” which had been developed for our first title Anomaly Warzone Earth, and which has constantly evolved from project to project. The primary benefit of this approach is that you gain a very reliable engine from the programmers’ side -- one that is easy to modify and adapt to different platforms or new technologies. The drawback is that it may lack some rapid-development goodies.

When making This War of Mine, the biggest addition to our toolset was a “Behaviour Tree Editor,” because all AI within the game utilizes Behaviour Trees. These can sometimes get extremely large. In fact, our AI designer, Radek Gwarek, usually worked on trees that were about 30 LCD screens wide. He has even calculated that if he displayed all the trees side by side on his LCD screens, they would be about 200m long.

How long did you spend working on the game?

Przemek: Less than two years. What was really crucial about This War of Mine's development was that we created the first prototype in about two months. And it was a serious experience from the start. We had mostly basic shelter, life and early scavenge locations, but these alone created such a huge emotional bomb with the first characters -- everyday food and health problems, mood, photos -- that we knew that was it. We knew that we must complete this game -- and we just can’t make it bad. The message was working very well with the game experience.

Another good thing we did was make a decision not to “overdo” some aspects of the project. Things like voiceovers, hi-poly characters etc. These would not add a lot to the game, but would require a lot of wasted effort.

How did you become inspired to create a game based more on survival than direct conflict?

Michal: From a civilian perspective war is about survival. People suddenly find themselves in situations that were never meant to occur. They are shocked and try to adapt. They try to protect their families and themselves the best they can. They struggle for food, medicine, shelter, things to keep warm during the winter; the really basic stuff that most of us living in developed countries have an abundance of. It came pretty natural to implement these notions into the game.

But there were also other factors. This War of Mine is a game about moral choices. It's meant to evoke strong emotional responses such as compassion, feelings of loss, fear of the future, helplessness as well as sometimes pride and satisfaction, when despite the odds we manage not only to survive, but also help others. This is why it is slow-paced, and gives the players the time to think through their situation and their decisions. We would lack all that, if direct conflict were the main theme. Not to mention that in real life direct conflict often results in sudden death or critical injuries, which is not the case in most war games.

The use of real faces, photographs, biographies and similar elements makes the experience feel very intimate. How did you decide on the characters that would be included?

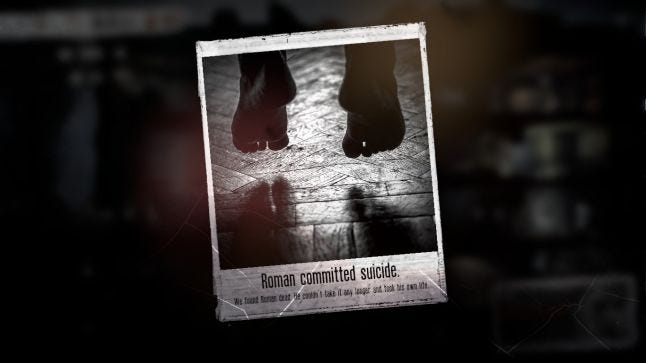

Przemek: As You said -- the most basic decision was to be real. Real in all aspects. That’s why we’ve decided to scan our bodies to the game. That’s why we’ve photographed ourselves. That’s why a lot, if not all, of the stories and biographies in the game are based on events we learned of during our research phase. Then we wanted to have different personalities in the game, all of them with thier own sad story to tell. You will play with “Roman,” who is a trained fighter, with no qualms with killing someone -- he has no regard for that, just survival. And on the other hand check “Cveta” – a bit of an older administrative worker. She's a woman who loves children and gets depressed in a bink of an eye.

There are no heroes, just normal people like us you can meet on streets. By the way – Cveta’s model and photos are based on our company accountant, and Roman’s our lead game designer. There's no clean-up, just raw, dirty, footage taken with a camera.

The game includes some random elements -- was it difficult to balance that while still giving the player a sense of hope?

Michal: Balancing the game was really important, and while it was not extremely hard because of good design decisions about the game-world architecture, it took a lot of time to tweak and test large Excel sheets of data. That was the job that Rafal Wlosek, one of our core team members, did very well.

In This War of Mine, we have different layers of randomness. I will just mention the most obvious one. The different sets of survivors, with different skills and morality, give the players different ways to adjust to this war-torn reality. Their strengths and weaknesses are both a replayability tool as well as one of the balancing elements. There are sets of predefined timelines which consist of different events scattered through time. The most prominent ones are winter-time and armed band attacks, and the more subtle include price changes of various items. All these things add some story value.

There are of course different locations that are randomly selected when the world is generated. Moreover, we also have many other random elements such as the visitors, etc., but there is simply too much to go into detail. The key to balancing out all these factors was to think of them as layers; layers that we could balance separately, with a minimum amount of cross-fade effect. This made the game both random and pretty well-balanced.

Have you played any of the other IGF finalists? Any you've particularly enjoyed?

Michal: Yes. I really love The Talos Principle. I enjoy its world in terms of gameplay, its puzzles and interactions, as well as the philosophical challenges it provides and the questions that cross my mind while playing this game. It really is fantastic when games are able to combine good gameplay with extra value that makes you feel differently, think creatively or experience something you haven't experienced yet. We are currently in a very exciting period in game development... a time full of new, interesting approaches and different perspectives on gameplay and games in general.

Przemek: I played some of the IGF games, and what can I say -- most finalists for me are winners. But the real killer is a game I haven’t played, I've just seen the movie. It’s Memory Of A Broken Dimension. Wow -- this art is just stellar. So real and unreal at the same time. Huge kudos to XRA!

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)