Rethinking Carrots: A New Method For Measuring What Players Find Most Rewarding and Motivating About Your Game

Why are we motivated to play games? Dr. Scott Rigby and Dr. Richard Ryan from think tank Immersyve deconstruct the 'carrot on stick' approach to game motivation, analyzing the basic psychological needs that games can satisfy.

Introduction

Gameplay strategies for motivating players largely focus on reward paradigms (“carrots on sticks��”) that dangle the sweet enticements of hidden levels, provocative content, and variations on the Sword of A Thousand Truths. But like all of us, don’t games want to be loved for who they are deep down, and not what they have?

Given the deep emotional engagement today’s games can elicit, it seems clear there are more meaningful motivational dynamics that lie at the heart of a player’s enjoyment. But what are they and how can we practically understand and measure them so we can build better experiences?

One of the biggest challenges to achieving such a model is that papers and mini-theories about the “player experience” of gameplay are multiplying like tribbles at a Barry White concert. This makes it very difficult for developers, who are dealing with greater pressures on their time and resources, to discern which approach (if any) will be of practical value. What makes this even harder is that there is often no statistically significant data to prove the real value of even good ideas about playtesting and measuring relevant aspects of the psychological world of players.

Here’s what we believe constitutes the four pillars of an applied player experience model:

It is practical to apply during development, providing meaningful and rapid feedback

It demonstrates an ability to accurately measure player experience variables that are statistically proven to relate directly to those things that matter to developers, such as player enjoyment, perceived value, likelihood to recommend, and sustained engagement

It empowers and facilitates creativity in development, rather than burdening it with a long checklist of requirements.

It brings together rather than expands on player experience theory and playtesting methodology (i.e. it moves us towards a “grand unified theory”)

Immersyve has been focused for the last several years on building and testing just such a model. The academic battalion of our founding group has clocked more than twenty years of empirical research into human motivation and has detailed specific motivational needs that we have been testing in the context of games, while our business contingent has pruned back any ideas (even good ones) that couldn’t be tied directly to tangible and practical value.

Here we will outline the elements of our model, citing examples from a variety of games, and review some hard data that indicates how it can help extend developers’ understanding of player motivation past “carrots on sticks” and increase their ability to measure motivation throughout development and even post-launch.

Sharpening Our Focus: Looking Deeper into the Measurement of the Player Experience

There’s no argument that the goal of games is to have fun, so it’s not surprising that many write about the topic. But fun and emotions are outcomes of psychological processes, and not the processes themselves. If we want to build better and better games, we need to look deeper and understand the dynamics that actually determine the emotional outcomes.

As an example, imagine you encounter your first rear-projection television and want to understand what’s creating the images on the screen. You can watch it from the front and very thoughtfully catalog the images being output, such as the thousands of colors on the screen or the pacing of images in different genres of shows. You might even scientifically measure how dramas have darker pixels and comedies brighter. From all this you may form some interesting theories about what is going on and how the television works. But if instead you had the blueprint of its inner electronics, you’d discover there was a very elegant system consisting of just three colored lights that explained all the myriad outcomes on the screen. You would have a concise and practical understanding of the fundamentals that would help you enhance the output and quickly troubleshoot problems.

In a similar way, our model diagrams the motivational lightbox that lies behind enjoyable and meaningful player experiences. This approach looks beyond emotional expressions and focuses on the basic psychological needs that games can satisfy. Just like the television’s lightbox energizes the myriad images that dance on the screen, our model is at the heart of the player experience regardless of genre, platform, or even individual differences in what players find fun. More importantly, the extent to which players are experiencing satisfaction of these needs can be quickly and objectively measured and show statistically significant relationships with enjoyment and immersion, as well as commercial outcomes such as ongoing subscriptions (decreased churn), perceived value, and a player’s intent to recommend/purchase sequels. In essence, we believe this approach represents a promising step towards a “unified theory” of the player experience that is both conceptually and methodologically useful.

Another way in which our approach differs from many others is that we are not merely collecting a lot of data about player behavior and then trying to read the tea leaves and take educated guesses at what they mean. We are starting with a detailed and well-validated model right out of the gate, then collecting data to test our hypotheses about how those motivational lights combine to create the engaging and fun experience all games strive to attain.

So let’s get into the details of this approach along with some real-world examples.

The Player Experience of Need Satisfaction (PENS)

A complete theory of motivation in the arena of gaming must not simply catalog observations of player behavior (e.g. “players like carrots” or “players pursue challenges”) but should also be able to describe the underlying energy that fuels actions in the first place (i.e. our “motivational lightbox”). Our research shows that this underlying motivational energy takes the form of three basic psychological needs: Those of competence, autonomy, and relatedness, which comprise the major components of what we call the Player Experience of Need Satisfaction (PENS). Over the last two years, we have conducted a variety of studies both in our game testing lab and with thousands of gamers in the field. Across the board, when games satisfy these motivational needs, it has significant implications for the player experience and the game’s success.

Methodologically, the PENS approach is easy to administer because it efficiently targets specific experiences related to need satisfaction and yields almost immediate feedback. These measures can be easily tailored to apply to specific design or gameplay ideas, or to more fully developed titles. Despite this simplicity, we’ll show some pretty exciting predictive relationships with a wide range of outcomes. It is the ease of the methodology combined with its predictive power that leads us to believe this approach is a strong addition to a developer’s playtesting arsenal, even during very rapid iteration of ideas.

Let’s look at each of the motivational needs in the PENS model more closely, and how they comprise the motivational lightbox that powers the outcomes developers strive to achieve.

Competence: The Need Behind Our Love of Challenge

Competence can be defined very simply as the intrinsic need to feel effective in what we are doing. Numerous studies have shown that in both our work lives and our leisure that we are intrinsically motivated to seek out opportunities to experience competence and the satisfaction that accompanies it. No matter what we’re up to, feeling effective energizes us and motivates further action, while feeling ineffective decreases motivation and brings a negative psychological impact.

Why do players find it rewarding to go through the exact same game content multiple times on harder and harder difficulty settings? Why do game challenges so captivate players and bring such exhilaration when conquered? Because overcoming game challenges satisfies the intrinsic need for competence and allows us to stretch our abilities, perhaps in a more immediate and direct way than many activities in “real” life. Whether its reaching the next level of Geometry Wars or unlocking “Insane” difficulty in Gears of War, the game is rewarding when it offers more opportunities to satisfy competence – and it is this satisfaction that gamers intrinsically value.

So we believe that the need for competence unifies and explains the energy behind many experiential outcomes coveted by developers such as “optimal challenge” and “flow”. But to demonstrate that a need for competence and the other components of the PENS motivational model are behind important outcomes (e.g. perceived value, enjoyment) we need to show that measuring competence satisfaction has predictive power as a playtesting method.

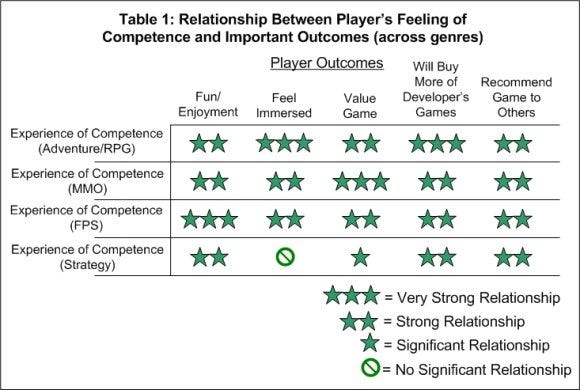

Table 1 summarizes the predictive value of competence satisfaction in relationship to a variety of relevant variables and across multiple game genres. As the table shows, gameplay competence is significantly related to the player’s enjoyment and sense of immersion, as well as how much value the player feels the game provides and a variety of other commercially relevant variables. This predictive value held true regardless of genre, thus demonstrating that the need for competence is globally meaningful as a playtesting tool.

Table 1 clearly demonstrates the strong predictive power of brief but carefully designed and validated PENS assessments of competence satisfaction. We should note that this approach can be applied in multiple ways during development, measuring how well specific design iterations meet competence needs, as well as illuminating how needs are differentially being satisfied at various points along the gameplay progression. As to the kinds of measurement questions themselves, remember that the goal with this method is to focus on underlying need satisfaction (experience of effectiveness) rather than emotional outcomes (such as fun and enjoyment). We find it valuable to ask players questions related to the experience of competence with regard to both gameplay and game mechanics (e.g. controls), and have consistently found both to have strong relationships to positive outcomes.

Notice in the above table that not only are the results strong for competence across the board, but where they are slightly less strong – for example, the relationship between competence and immersion in strategy games – makes conceptual sense. Feeling competent at adjusting city production during a round of Civilization IV is not as likely to “pull you in” to the game world nearly as much as making an uber headshot during a heated round of Counter Strike. As we’ll see below, other motivational needs, notably autonomy, shine more brightly behind the enjoyment and immersion in strategy games.

Let’s look at autonomy next, as it is the second motivational need in the PENS model.

Autonomy: The Need Behind Our Love of Freedom

The second intrinsic psychological need of the PENS model is autonomy, which is the experience of volition or choice in one’s decisions and actions. In activities in which we feel we have the freedom to choose and create the experiences we want for ourselves, we are more likely to be energized and intrinsically motivated to engage in those activities. There’s no way to fudge this -- choices that are forced upon us don’t count and are actually demotivating. In gameplay, these can include such things as our avatar being taken out of our control too frequently by cut-scenes, running into invisible walls, or generally gameplay that gives the illusion of choice (e.g. you are free to cut the blue wire or the red wire to defuse the bomb) when in fact there is only one solution to a challenge or one path to follow (e.g. red wire = boom).

The intrinsic need for autonomy is what fuels the player’s hunger for more freedom in games, and why games that provide freedom and open-ended gameplay are so highly valued. The best examples are “sandbox” titles, such as the Sim City, although our data shows that all game genres benefit from supporting player autonomy.

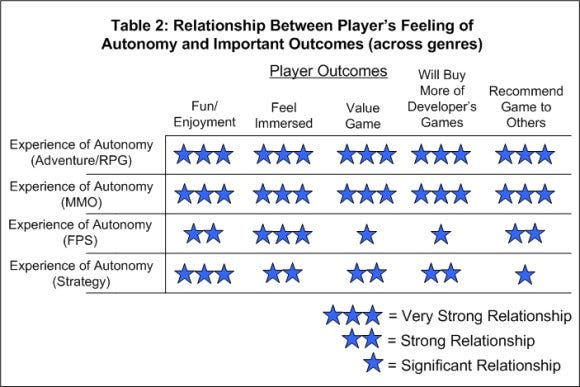

We found that when looking at turn-based strategy games, player’s experience of autonomy was by far the greatest predictor of enjoyment – showing a correlation of nearly .50. This indicates that a large proportion of the enjoyment of the game was directly related to the player’s experience of autonomy. Similarly strong relationships were found between satisfying the need for autonomy and commercially relevant outcomes, such as game value, intent to recommend game to others, and desire to play more games by the developer. Table 2 provides a snapshot showing the global value of measuring the experience of autonomy across genre.

As the table shows, the experience of autonomy showed consistent relationships with important outcomes regardless of genre or platform (much as we found with competence). This is particularly true in MMO’s (e.g. WoW), Strategy (RTS and TBS), and Adventure (e.g. Zelda) genres. The broad ability of autonomy to significantly predict outcomes lends further support to our hypothesis that PENS is a global model. Conceptually, the autonomy need lies at the heart of efforts to create open-ended gameplay and the broad trend to grant players more and more choice in customizing multiple aspects of their gaming experience.

The strength of the intrinsic need for autonomy also explains other aspects of player behavior as well, for example, the incredible persistence of many players to “break” the game (as Will Wright sometimes puts it). Head over to YouTube and you can find an increasing catalog of videos that demonstrate players remarkable persistence in discovering ways they can stretch their freedom in virtual worlds, particularly to go beyond what even the developer intends. The PENS model gives us the means to both understand this important need for autonomy, and objectively measure how well we are providing it in games.

The final basic motivational need in our lightbox is that of relatedness, and we turn our attention there next.

Relatedness: The Need Behind Our Love of Connecting

Relatedness is the third intrinsic need that comprises the need satisfaction model of player motivation. While it has been an important motivational variable in areas outside of gaming, only in the last few years as multiplayer games and functionality have grown in popularity has relatedness started to have increased relevance to the mainstream player experience.

Relatedness can be defined as the intrinsic desire to connect with others in a way that feels authentic and supportive. For those of you putting together the next zombie-slaying FPS, you might think this a good time to slip away and fix yourself a snack, and to a certain degree you may be right. But as with the other two intrinsic needs, relatedness is a core motivational need that it is important to satisfy across genres and throughout the player’s experience. Our data shows that wherever there is a multiplayer component to games that allows players to build real relationships with those with whom they play, either as teammates, guildmates, or social friends – having the opportunity to connect intrinsically satisfies and energizes. Whether it’s “Parties/Guilds” in World of Warcraft “Gangs/Corporations” in Eve Online, or your favorite teammates in FPS games such as Counterstrike – virtually all of these multiplayer game features enable the experience of relatedness and contribute meaningfully to the player’s motivation and enjoyment.

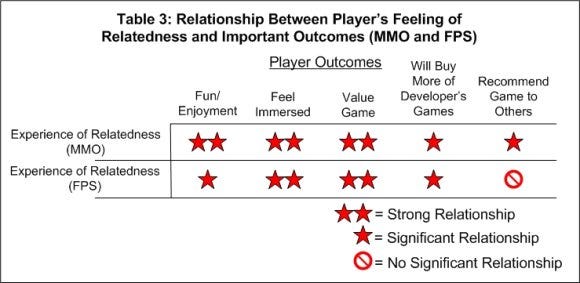

Our research shows that particularly in MMO’s and multiplayer FPS games, relatedness plays a significant role in enjoyment, perceived value, and sustained participation in games. Table 3 summarizes a snapshot of these findings within these two genres. We are also currently looking into relatedness in other contexts, such as multiplayer strategy games, as well as the possibility that as AI continues to improve that even computer characters will be able to interact with players in such a way that relatedness needs can be met. In general, as games continue to increase in their ability to connect players with greater degrees of expression and effectiveness, we expect relatedness will continue to gain in its importance.

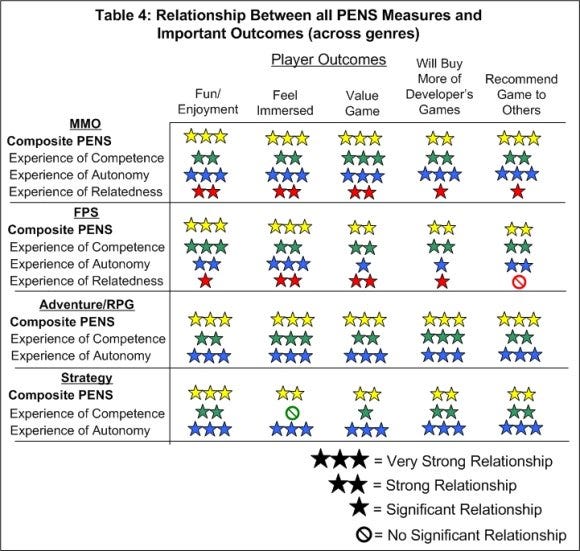

Now that we have outlined all the major components of the PENS model, we can put together a complete correlation table to show how each of our needs is contributing to meaningful outcomes across multiple genres. Notice how just as the red, green, and blue lights in a projection television combine differently to produce different outcomes, the motivational needs in our lightbox combine with varying degrees of strength depending on genre. For example, in sandbox strategy games, notice that the major contributor to most outcomes is the experience of autonomy, which is what we’d expect.

We also are including a variable called “Composite PENS,” which is the sum of all of the motivational needs in the PENS model (i.e. competence, autonomy, relatedness) pulled together into a global motivational score

On the whole, notice how in almost all cases each of the needs is contributing significant predictive power to both the player experience and commercial outcomes such as perceived value.

Show Me the Money: Why the Measurement of PENS Can Surpass the Measurement of “Fun”

We’ve outlined the core elements of the PENS approach and highlighted some of the strong relationships with important outcomes, both with regard to the player experience and commercial success. Next we would like to present some more of our data in detail, taking the full PENS model into account and looking at the power of our complete motivational lightbox when competence, autonomy, and relatedness are working together to create the player experience.

Remember that one of our hypotheses is that the PENS variables are the power behind things such as enjoyment and perceived value. Hence our data needs to show that PENS is where the deeper action is. We accomplish this objectively through a variety of analyses, but will here focus on correlations and regressions.

A quick note on regression analyses for those who are unfamiliar with them. Regressions allow you to determine the relative contribution of different factors to your outcomes. As an example, let’s say you want to know what factors contribute to good grades in the classroom. You find two variables predict good grades: Student motivation and sitting towards the front of the class. To raise grades, do you focus on student motivation or reconstructing classrooms so more students sit near the front? Or both? It is important to know the relative contribution of variables to outcomes, and how one (motivation) may be behind the other (sitting at the front). Regression analysis allows us to do just that: We can look at groups of variables and see their relative contribution to outcomes. We can give credit where credit is due.

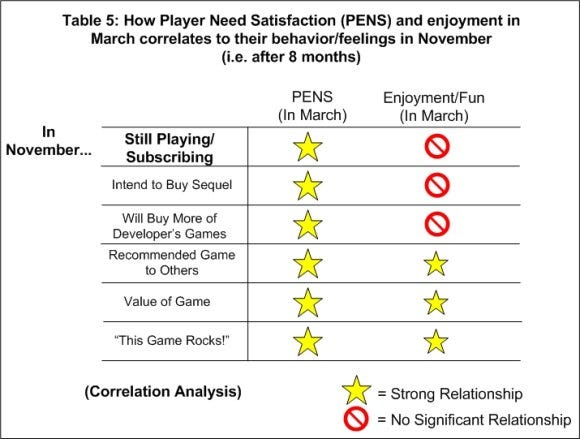

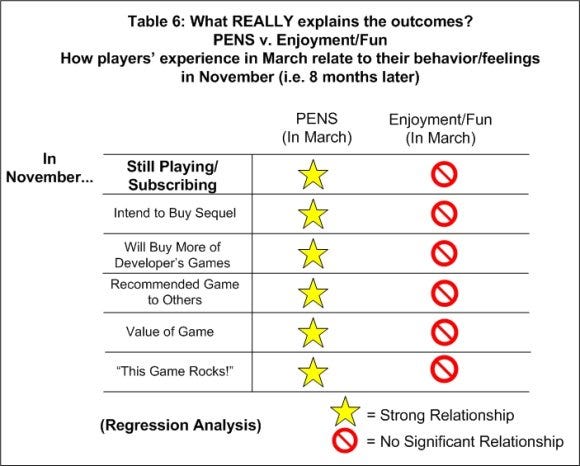

So let’s now illustrate this using two factors in our data: game enjoyment and the PENS measures. We recently finished an eight month longitudinal study of MMO gamers in which we asked them in March about their experience of fun/enjoyment (i.e. the usual kinds of questions developers ask during playtesting), and also asked them about their experience of need satisfaction in areas of autonomy, competence, and relatedness (i.e. the PENS model). We then talked to them again eight months later in November to see if they were still playing the game they reported playing in March, and to get their impressions of the game and its value.

For those still playing the game after eight months, our model showed better predictive value than enjoyment in the correlations, even though both related positively to enthusiasm (“This game rocks!”), and perceived value (see Table 5)

You might think this means enjoyment measures are a reasonable alternative to PENS and can equally predict some outcomes. But our data shows they don’t. When we ran our regression analyses to see who is really pulling their weight (remember the motivation v. front of the class issue?), the PENS measure related strongly to all of the outcomes, while enjoyment questions did not. In other words, only our need satisfaction components predicted these important outcomes, including sustained subscriptions, as seen in Table 6.

This directly supports our hypothesis that it is the deeper need satisfaction that is experienced in games that leads to their success, both in the direct emotional experience of the player (i.e. “This game rocks!”) and in commercial outcomes (such as perceived value and future intent to purchase). Apparently what “rocks!” about games is that they satisfy motivational needs, supporting our contention that our motivational lightbox lies behind the experience of enjoyment, and more directly measures what is important to the gaming experience in order to catalyze sustained player enthusiasm and commercial success.

How does this contribute value directly to a game’s bottom line? As the tables above show, in this MMO study only our model was able predict future play eight months later. Fun/enjoyment measures did not relate to continued play. Based on the data, we estimate that an MMO developer could increase retention (decrease churn) by 15-20% if they tested gameplay ideas using a PENS approach, which based on today’s subscription rates (i.e. about $15/month) roughly equates to about $25,000 in additional revenue every month for every 10,000 players. For a game with 100,000 subscribers, that could mean $3MM in revenue each year (mostly dropped right to the bottom line).

Let’s look at another study that shifts the focus from MMO’s to two adventure console games…

Experiencing Need Satisfaction: The Key Ingredient of Successful Games

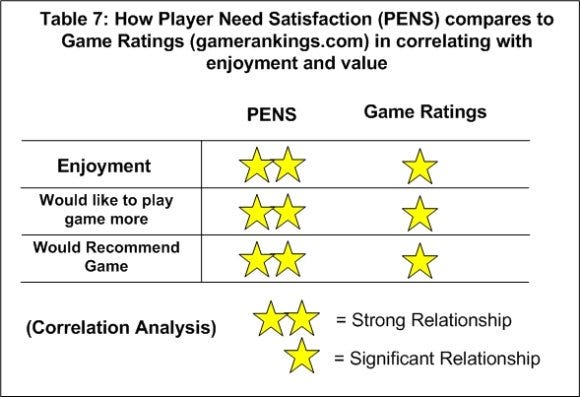

In another study, we wanted to compare the PENS model to two games that are already proven to differ in terms of their critical and commercial success. To do so, we chose two adventure games (Nintendo), one highly rated and one poorly rated, based on their rankings at gamerankings.com. We like gamerankings.com because it is pulling together rankings across users and many review sites, and hence is less prone to bias. The highly rated game (98%) was Ocarina of Time (surprise, surprise) and the poorly rated game was A Bug’s Life (57%), chosen because it had both a low rating and was a similar genre/platform to Ocarina (we wanted the major difference to be quality, and not genre/platform).

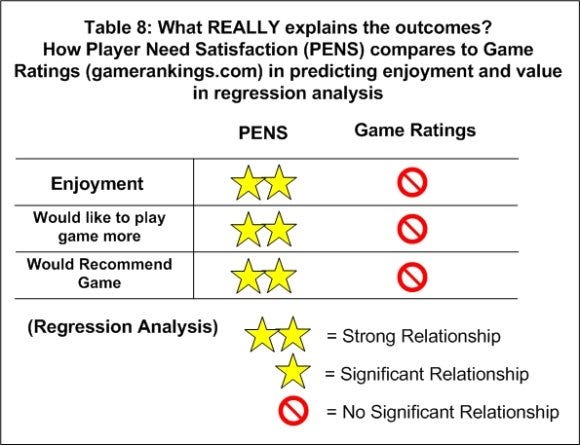

First, as a way of validating that our PENS measures actually predict game quality, we had participants play each game in our lab and rate their experience. Zelda had significantly higher scores on our measures, as well as having higher scores on both enjoyment and the player’s prediction of how long into the future the game would continue to be fun for them to play. The significant correlations are summarized in Table 7.

PENS had roughly twice the power that game ratings did in predicting enjoyment and value, but both the PENS method and game rankings were significantly correlated with outcomes. Then we ran a regression with both PENS and game rankings competing to see which was really responsible for predicting outcomes. As in the last study, the PENS measures continued to be highly predictive of both enjoyment and perceived value, while game rankings lost their predictive value. In other words, the empirical evidence (summarized in Table 8) shows that it is the satisfaction of needs that is the real hero behind enjoyment and perceived value, and perhaps also what lies at the heart of high rankings in the first place.

The PENS as a Global Test of a Game’s Appeal

Next we address the question of individual differences between players. Since some gamers like to pwn n00bs on the Internet and others like a quiet game of Bejeweled, is the PENS model always able to predict what a player will find enjoyable? To further test whether our model is a unified theory, we conducted another study in our lab in which we had subjects come in on four separate occasions and play four different games of different genres. Each time games were rated by players in terms of their enjoyment and preference, along with the PENS measures. Using some more fancy statistics (hierarchical linear modeling) that are detailed in a technical paper elsewhere, we demonstrated that regardless of individual differences in the kinds of games people prefer, the PENS model predicted not only enjoyment, but whether or not the individual expressed a desire to continue playing a particular game during a free choice period. This supports that the model is not only applicable across genre, but also across individual differences in game preference. This further contributes to its parsimony and its value in playtesting.

Another very important point from this study: Keep in mind that the participants were not just gamers, but were drawn from a more general population. This directly indicates that games that satisfy the needs in the PENS model may implicitly appeal to a broader audience and larger potential market.

When It Comes to Carrots, “Context is King”

We began by talking about the prevalent use of carrots in gameplay design as a means of motivating players. What we hope the data here has shown is that there are much more important qualitative aspects of gameplay that can be easily measured and that more fundamentally drive sustained enjoyment and perceived value without contributing to a “new content” feeding frenzy. In fact, we often ask players about how important in-game carrots and rewards are, and we find that there is only a small relationship to the need satisfaction measures of the PENS model.

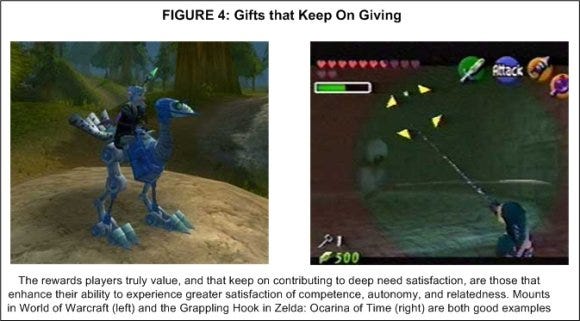

When we look at the analyses involving the PENS measures and the player’s valuing of in-game rewards, we find much stronger relationships between our need satisfaction components and outcome measures. In fact, our data indicates that there is a very important point to keep in mind when developing carrots – they are most motivating when they specifically enhance the player’s experience of competence, autonomy and relatedness. A good example of this would be the qualification for a mount in World of Warcraft at level 40. It is surely a reward, but it also enables both greater autonomy (i.e. ability to explore) as well as contributing to one’s competence in travel. Another good example would be the grappling hook in Zelda: Ocarina of Time, which not only increases your arsenal to be competent at game challenges, but also vastly increases your autonomy in exploring the gamespace. We recommend that when considering the creation of that next shiny bauble that developers always ask themselves how it will specifically enhance need satisfaction before dedicating the resources, as the payoff for players in both enjoyment and perceived value is only present when more fundamentally needs are satisfied.

Putting the PENS to Work

As we mentioned above, one of the goals in the creation of this model was to put forth a parsimonious methodology that could allow for rapid but accurate feedback. All of the data presented here was achieved by surveying the player’s experience of competence, autonomy, and relatedness in the context of gameplay – an approach that can be easily integrated into the protocol of most playtesting methodologies, or used as a stand-alone measure to get a strong first impression on the motivational value of design ideas.

Much like a good game, we do want to emphasize that the creation of a valid PENS measure that has the kind of predictive power we’ve demonstrated here requires iteration and the involvement of an experienced research methodologist/statistician on your playtesting team. While part of the heuristic value of the PENS model for developers is that the motivational needs we’ve outlined are easy to grasp conceptually, they are also nuanced and developing accurate measures for them is a more involved science. We’re happy to make available upon request a journal publication that details more of the technical aspects of much of the work that is discussed here.

A few other words on the strengths and weaknesses of the PENS model and methodology as it stands today. Immersyve has put several years and hundreds of hours into validating the approach, but it is relatively new in the field of gaming and will no doubt develop even more value as developers put it to work on specific projects and it becomes a more granular tool. That said, it is a method that today shows strong value regardless of genre or platform as it goes right to the heart of what’s important about the overall player experience and to factors that are important aspects of critical and commercial success.

Currently we have several additional studies nearing completion that we anticipate will increase the predictive ability of our PENS measures even further as a playtesting tool. An even more interesting project that is nearing completion is the creation of standardized PENS scores that for the first time will allow developers to meaningfully benchmark the player experience, comparing their title to best-in-class titles. We’ll have more to report on these fronts very soon.

Conclusion

Immersyve set out several years ago to bring a true applied theory of motivation to the gaming industry that would meaningfully contribute to developers’ understanding of what fundamentally motivates players beyond carrots on sticks. Methodologically, we also wanted to provide a practical playtesting model that respected the increasing pressures put on developers – one that demonstrated predictive value while minimally intruding on the production schedule.

The Player Experience of Need Satisfaction model (PENS) outlines three basic psychological needs, those of competence, autonomy, and relatedness, that we have demonstrated lie at the heart of the player’s fun, enjoyment, and valuing of games. By collecting players’ reports of how these needs are being satisfied, the PENS model can strongly and significantly predict positive experiential and commercial outcomes, in many cases much more strongly than more traditional measures of fun and enjoyment. And despite the simplicity of the model conceptually, it shows promise as a “unified theory” of the player experience by demonstrating predictive value regardless of genre, platform, or even the individual preferences of players.

In addition to its practical value as a playtesting tool, we also believe PENS brings conceptual value to the games industry in three specific ways:

PENS is a useful heuristic model of player psychology that developers can easily understand and tuck in their pocket. Creating a great game will always be an art and not a science – but having a compact understanding of a player’s motivational needs can catalyze innovation and help to vet specific design choices.

The PENS model and methodology can embrace innovation well into the future without falling prey to “feature creep.” One of the challenges of playtesting methodologies that focus primarily on mapping player behavior is that games and technology are constantly expanding behavioral outcomes (case in point: The Wii). This creates a moving target that behavioral measurement approaches must continually chase. By contrast, the motivational lightbox of the PENS model is a constant – it is measuring the fundamental energy of the player experience, regardless of its outward expression.

Describing the player experience in terms of genuine need satisfaction, rather than simply as “fun,” gives the industry the deeper language it deserves for communicating what makes games so powerfully unique. It allows us to speak meaningfully about the value games have beyond leisure and diversion, diffuses the political bias against games as empty experiences, and provides an important new lexicon in the Serious Games arena where, as the name implies, fun is not always the primary goal. When we speak of games in terms of their satisfaction of competence, autonomy, and relatedness, we respect that this is both what makes them fun and also what can make them so much more.

We look forward in the near future to reporting further on the development of the PENS model, and hope that these ideas continue to prove their value to developers and playtesting.

Additional Resources:

Ryan, R., Rigby S., & Przybylski, A. (2006). “The Motivational Pull of Video Games: A Self-Determination Theory Approach”. Motivation and Emotion, Springer Science and Business Media (reprints available)

Rigby, S. (2004). Player Motivational Analysis: A model for applied research into the motivational dynamics of virtual worlds (.pdf available)

Contact Immersyve at [email protected] or visit www.immersyve.com to request these resources and for more information.

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)