Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Recently, the original creators of the world's first massively multiplayer online role-playing game got together with other game developers to bring a history to the present.

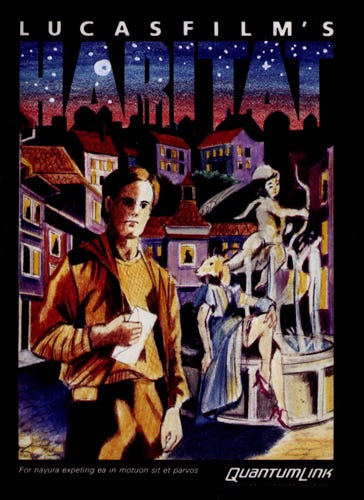

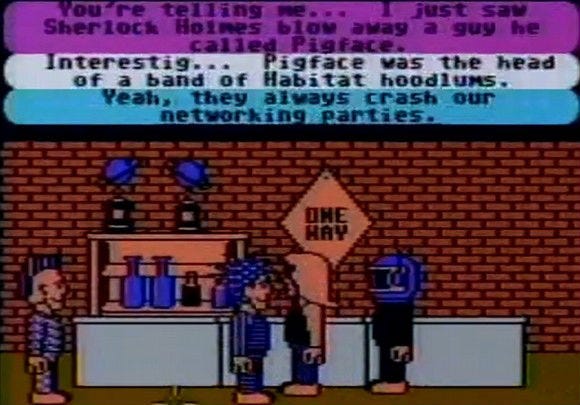

In the spring of 1986, Lucasfilm Games released the beta version of Habitat, the first commercial, graphical massively-multiplayer online role-playing game that the world had ever seen. Set in a virtual world and using on-screen avatars, users could see, speak, interact and trade with each other, sometimes robbing each other of possessions and body parts as well as randomly turning into spiders or monsters. The game’s core rules stated that the players would govern the environment and make the world around them. With the exception of only a few avatars to prevent outright chaos, players were left to their own devices.

This was a new kind of game that would pave to way for almost every MMORPG to follow.

Sadly, it wouldn’t last. By 1988, Habitat had been closed down at the end of a two-year pilot run with Lucasfilm Games. Other incarnations would appear — the game eventually was licensed to Fujitsu, which would spend and lose millions of dollars on the game before shuttering the project. Habitat, as the world knew it, was now essentially in cold storage with the decades and any hope of support or maintenance for the title slipping away.

With Habitat being honored at this year’s Game Developers Conference, Alex Handy, founder and director of the Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment (MADE) stepped in, sent out inquiries to Habitat creators Randy Farmer and Chip Morningstar as well as Stratus, the makers of the Nimbus servers Habitat had originally run on. Handy, who coordinated communication between the founders, server engineers and everyone in the development community interested in working on the project, began to work to acquire the resources needed to begin bringing Habitat back to life.

“It just sort of came together. I felt sort of obligated to try to get this thing back together and I certainly didn’t know how to do this myself, so I reached out to some very smart folks all around the world and a lot of them are in this room today trying to get this thing back online,” said Handy. “A lot of the things that we see in modern MMORPGs originated in Habitat. The fact that people love cosmetic items, the fact that if you change things in the world, the user base will freak out…they created the ability to murder people in the game, there was a disease, there were quests…it’s extremely valuable for us to preserve the history of those things and this is doing that.”

“It just sort of came together. I felt sort of obligated to try to get this thing back together and I certainly didn’t know how to do this myself, so I reached out to some very smart folks all around the world and a lot of them are in this room today trying to get this thing back online,” said Handy. “A lot of the things that we see in modern MMORPGs originated in Habitat. The fact that people love cosmetic items, the fact that if you change things in the world, the user base will freak out…they created the ability to murder people in the game, there was a disease, there were quests…it’s extremely valuable for us to preserve the history of those things and this is doing that.”

The first step of the process was to get permission to bring Habitat back online, even with Fujitsu keeping it mothballed throughout the ages. For this, Handy went to MADE staff member and Bay area linguist Chris Wolf, who provided translation between Handy and executives at Fujitsu.

“They pretty much gave the go-ahead from the first couple of emails after some rough clarification on what we wanted to do,” said Wolf. “When they saw that we were interested in hosting the online Habitat game once again, they seemed very thrilled to see an old project of theirs given new life.”

With Habitat’s local founders and developers being wrangled towards the MADE’s Oakland, California location, Handy then emailed Paul Green and John Biogiovanni of Stratus Technologies to see about acquiring a server that was the appropriate vintage to run Habitat in. Green, in turn, was able to acquire a Stratus Nimbus server built in 1989, spent months physically cleaning and repairing the server on nights and weekends, upgraded the version of VOS (Virtual Operating System) it was running to a version developed in 1999 that could handle the TCP/IP protocol, then shipped it west to Oakland.

“Alex contacted me, said ‘we’re trying to bring Habitat back to life, it ran on a Stratus computer and do you know where we could get one?’ I said ‘yeah’, I had one in my basement and my wife has been bugging me for years to get rid of it and here’s the perfect reason to get rid of it,” said Green, who flew from Boston to Oakland to be on-hand for the hackathon portion of the project.

The Nimbus, in turn, arrived at the MADE video game museum around the end of September on its own cargo palette. Weighing more than 300 pounds and being about equivalent to the size of a great dane, MADE volunteers pushed, pulled, yanked, wrestled and cajoled the machine into place for work to bring it back to life as the world’s only remaining Habitat server.

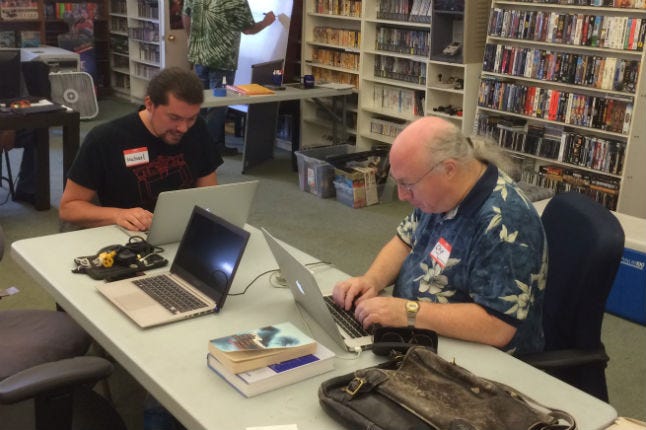

On the morning of Saturday, September 25th, more than a dozen hackathon attendees - as well as several attendees working remotely and communicating through the #made IRC channel - came together at the MADE to begin the process of bringing Habitat back to life. The group gathered around Habitat creators Chip Morningstar and Randy Farmer as they drew out a guide path on a whiteboard, assigning the teams to either work on the Stratus server, build a virtual machine with a traffic monitoring server or begin the task of getting the server’s communications protocols online and talking with more modern protocols in order to put the server online.

“It was really great to see this thing, to see these commands I hadn’t seen in 25 years, for it to actually run and we’re on our way to doing something useful,” said John Bongiovanni, who helped build the Nimbus server for the project and had worked with this machinery and the VOS operating system in the 1980s.

Although the Nimbus server (seen right, with "cooling system") was technically online and visible via the internet, the key challenge of the project came in reproducing the Qlink protocol which Habitat used as its means of communication during its initial tenure from 1986 to 1988. It was here that only about 80 percent of the original Qlink protocol - and its documentation - had survived, the language having been poorly maintained over the decades. This was also where an open source project, known as Quantum Link Reloaded, came into play, maintained by fans of the original Qlink protocol who recreated Qlink’s functions and system calls under modern technology. In addition to this, the human capital of Morningstar, Farmer, and everyone else involved, were able to recreate old Qlink code and test it on the fly.

Habitat co-creator Randy Farmer explains the day’s milestones to hackathon attendees.

“My responsibility for this project is basically being a resource — all this knowledge as to how this whole thing worked, how it was put together on the server side,” said Morningstar. “We’ve got a bunch of archival sources which are missing a lot of the Quantum Link infrastructure that will have to be reconstituted now and figuring out what the points of contact between our code and that code were since I was involved with all of the design of the server code and all of the communications protocols.”

When asked as to whether recreating the Qlink protocols was similar to the fictional practice of splicing in amphibian DNA to fill in the gaps a la the movie “Jurassic Park,” Morningstar sat back and laughed.

“Yes, well, I’m probably going to be creating frog DNA,” he said.

“The biggest challenge right now is that we don’t have complete source code for all the support libraries that the server had. So, I imagine that’s going to be the big nut. I think there’s going to be a lot more work to emulate the missing pieces of Quantum Link for the server,” said Farmer. “I was talking with Chip [Morningstar] and saying, ‘didn’t we do the impossible 30 years ago and we swore we’d never do it again?’ And I guess we’re breaking that promise.”

Habitat co-creator Chip Morningstar (right) studies communications code before the hackathon begins.

Even with the Qlink language needing to be rebuilt, the teams were able to: Make an effort to recompile the Habitat source code; work on a tarball function that was taking its time (but working); and set up a traffic-monitoring server created from a QuantumLink Reloaded virtual machine, allowing project participants to study what code worked and what didn’t. Sometime in the middle of the afternoon, the Nimbus server went online and could be logged into across the internet via SSH with system administrator Ronald “Setien” Cotoni beginning to build user accounts for anyone interested in contributing to the Habitat restoration project.

As afternoon turned into evening and people began to venture home, the core group consisting of Chip Morningstar, Randy Farmer and assorted other developers sat around the table, checking in with contributors corresponding via an IRC channel and testing new ideas. What had begun as an offhand lunchtime quip between Morningstar and a coworker at Lucasfilm Games 30 years ago about humans being more interesting to play with and against online in a virtual environment as opposed to an artificial intelligence had placed this group of people around a table with laptops three decades later, complete with each person offering new ideas as to how to make the game work and testing their ideas to see how they’d worked. It’s a slow project and probably the basis of a few more hackathons to come, but they’re recreating the Qlink protocol and were able to successfully send and receive packets as well as begin playing small segments of Habitat by the end of the evening.

The first MMORPG ever created is being rebuilt, reconstructed and preserved.

Not bad for a Saturday.

If you’re interested in participating in the Habitat Restoration Project, go to the Hatchery Wiki, the MADE Habitat Wiki, made.q-link.net, or the Google Doc for the project.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like