Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Feelplus' president Ray Nakazato (Lost Odyssey) talks to Gamasutra about the business of games from a Japanese perspective, revealing exclusive insights on titles from Ninety Nine Nights to the Sakaguchi-helmed RPG, and beyond.

Ray Nakazato has had his fair share of jobs, from the early days of programming PC games in Japan, to his time at Broderbund, then EA Japan, Capcom, and Microsoft Game Studios, all the way through to his current position as president of FeelPlus studio, working on Lost Odyssey with Final Fantasy creator Hironobu Sakaguchi.

Nakazato was a speaker at GDC Prime this year, and Gamasutra took the opportunity to interview him extensively about his past and present experience. He offers a refreshingly honest perspective on all aspects of the Japanese industry, speaking plainly about subjects most developers shy away from, diminish the importance of, or dodge entirely. These subjects range from the Japanese perception of the PS3 and 360 and the future of game technology in the region, to the status of notable industry figures such as Shinji Mikami (Resident Evil), Yukio Futatsugi (Panzer Dragoon), and Yasumi Matsuno (Final Fantasy XII).

We also spoke at length about Lost Odyssey, including a few new gameplay details, the problems with Ninety-Nine Nights, and, in brief, a canceled 360 project from Game Republic’s Yoshiki Okamoto.

GS: Can you talk about your personal background in games?

Ray Nakazato: When I was in junior high, I started coding games. Back then, in the mid-70s, there was nothing. I was into coin-ops at the time, and you’d really only see a couple of new games at a time. And one day I heard of this thing called a personal computer, and you could actually make your own games. So I got a PC, and studied how to program. Then I started making games, but just for fun. The first commercial game I made was in 1983. It was an 8-bit PC game called Chobin. It was only distributed in Japan.

GS: What platform was that for?

RN: The PC-88.

GS: Ah, an NEC.

RN: Yes – so that was the start of my professional career. Then I started making games for this small PC publisher, BOTHTEC.

GS: Aren’t they still sort of around?

RN: They were…I think they are, but in a different form. They once became a company called Quest. They did Ogre Battle, among other games.

Classic console shooter Magical Chase

GS: And Magical Chase?

RN: Right. Anyway, I started making games for this company, and back then, the biggest game I made was called Relics. It was only released in Japan, and it sold about 100,000 units. As a PC game in Japan, it was a big hit. Then, in 1988, I came to the States, and was hired by Broderbund to bring those Japanese PC games to North American platforms. Back then, PC games were spread across many platforms, all of which were incompatible with each other, so we picked some of the best Japanese PC games and ported them over to Apple, Commodore, and IBM PC-XT.

I did that for a few years, but it didn't go well, so Broderbund decided to stop that business. After that, I was at Maxis, doing some SimCity stuff, but they moved to Canada after they were hired by EA. Back then it wasn't even EA, it was a company called Distinctive Software. The day I got hired by DSI was the day they were bought by EA, so it became EA Canada. That was 1990 or 1991.

Back then, EA Canada got big funding from a Japanese firm, to make an RPG for some console, and on PC as well. So I got hired by EAC to participate in the project. Then, EA decided to get into the Japanese market, so I helped out with bringing out Japanese versions of EA games. When I came back to Japan, it was to help out 3DO, actually. 3DO at the time was half EA and half Panasonic, project-wise.

GS: Hardware, or software?

RN: 3DO is really a technology. The hardware was by Matsushita, and first-party products were done by EA – something like that. After that, I went back to EA Japan, and just started publishing EA games in Japan. We also started making games specifically for the Japanese market. I think there was only one game I did while in Japan that was published globally. It was called CrossFire, but in the States it was called X-Squad. That's one of the very early PS2 games.

Then I went to Capcom after that. At Capcom, I was asked to start up a Tokyo studio, since Capcom's headed in Osaka. I was hired by Yoshiki Okamoto, who later left Capcom. I started hiring people from Tokyo, and did some online projects as well as some games that were being done outside of Japan like Maximo, which was done in the States. I was in charge of Maximo. We were also making a game called Red Dead Revolver - a Western shooting game - which was being done by a studio called Angel Studios, in San Diego. They got bought by Rockstar.

GS: I forgot that Capcom was originally supposed to publish Red Dead Revolver.

RN: We were funding it, so we then canceled the project and sold it to Rockstar. It was later published by Rockstar. There were also a couple of projects from the French, and a couple of projects in England, although they didn't make it. There was also Chaos Legion, Settlers of Catan, based on the boardgame, and Onimusha Tactics for GBA. That's what I was doing, and bringing American games to Japan as well.

The biggest success on that side was Grand Theft Auto. Capcom was the exclusive publisher of Grand Theft Auto III, Vice City, and San Andreas in Japan. That was a hard thing. Rockstar was a little hard to deal with, but the more difficult thing was with Sony of Japan. We had to convince them to give their permission to release the GTA games in Japan.

So with Capcom, it was online games, bringing games to Japan from overseas, as well as some original games that were being done outside Japan. I joined Microsoft when they were getting ready for the Xbox 360. That was recently, in 2004. We started six projects at Microsoft Game Studios Japan. The first one we finished and released was called Every Party, with Yoshiki Okamoto at Game Republic. The second one was Ninety-Nine Nights, with Tetsuya Mizuguchi. I was actually in Korea for about a year to fix this project.

Rockstar Games' Western-themed Red Dead Revolver

GS: What was wrong with it?

RN: It was just going so wrong. So I was there, Mizuguchi was there, to kind of sort it out. But it slipped by about three months, and we were shooting for launch. It came out a little later. Then one project that we were doing with Mr. Okamoto (and Game Republic) was canned.

GS: What was that project, if you can say?

RN: It was a third-person shooter game with a Japanese samurai. Kind of half historical, half sci-fi. Then came three RPGs: one was Blue Dragon, another was Lost Odyssey, and Infinite Undiscovery. I started those six, but Ninety-Nine Nights was going so bad, I had to spent 80% of my time on that until it was done.

Now we have three projects left. Out of those three, Lost Odyssey was our biggest, and wasn't going that well, so my boss asked me to take over the project and fix the problems. I had to physically relocate to Feelplus Studio.

GS: Did you start Feelplus?

RN: No...well Microsoft and Hayao Nakayama, who founded AQ Interactive (also ex Sega boss), discussed it. Lost Odyssey was once an internal (Microsoft) project that was done by my staff anyway, but it wasn't going well. One of the reasons it wasn't going well was because it was an internal project, and Microsoft’s culture and systems made it harder – we couldn’t go smoothly.

That's when we decided to make our team an independent studio, and I asked Mr. Nakayama to found the company. I then moved in several Microsoft people into that studio, and also hired a good number of people into that studio. Mr. Nakayama and I, on behalf of Microsoft Japan, discussed starting up a company, but it was originally managed by one of Mr. Nakayama's people. I joined that company a little later, after I finished Ninety-Nine Nights.

The impressive-looking Xbox 360 exclusive RPG Lost Odyssey

GS: Was Lost Odyssey spearheaded by (Final Fantasy creator) Hironobu Sakaguchi to begin with?

RN: Yeah. Discussion for the project started in 2003 or 2004.

GS: You mentioned that Microsoft has a difficult structure for Japanese developers. Why is that?

RN: One thing is the cost. Man-month cost is very high. Not salaries, but being a Microsoft employee is expensive. We have a fixed amount of budget, and with Microsoft's man-month cost, we can only do so much. But if we move the company (external), per-person, per-month cost goes down, so we can do more. So that’s one thing.

Recruiting was another problem. We had to recruit a lot of people, and Microsoft as a company has a very high bar to hire people in. The person has to be generally superior in all areas, but game specialists, in general, are often great in one area and not so great in others. It was very hard to meet all of the hiring criteria that Microsoft had, so it was hard to hire people. Stuff like that.

GS: And how did AQI come together?

RN: Mr. Nakayama, the founder and former chairman of Sega, left Sega.

GS: When was that, again?

RN: Right around when they were doing the Dreamcast, (Shoichiro) Irimajiri was the head of Sega, and Nakayama asked him to do all the console stuff, while he himself was doing arcade only. Then around 1997 or 1998, he started a human resource outsourcing company. It was very successful, and it went public. Then he wanted to come back to the gaming industry. He's an old man, but he's very passionate. He started a company called Cavia, a development studio, in 1999 or 2000 with a lot of people from Namco. Then a former Sega executive, Yoji Ishii, founded Artoon - just around the same time. He asked Nakayama to fund a little bit of it, so Artoon started with Ishii's own money, but also Nakayama's money as well. It was kind of a brother company: one managed by Ishii, while the other was managed by Nakayama. After five years, they decided to merge together to make it bigger - big enough to go public.

Just around that time, Microsoft asked Nakayama to establish a formal company - that's Feelplus - and moved Microsoft people in and started hiring people to do Lost Odyssey. So Nakayama hired Cavia and Feelplus, then Artoon merged into this group and (he) made it AQI Group.

AQI is a holding company as well as a publishing arm of those three studios, but those three studios mainly make games for first-party publishers like Microsoft and other third-party publishers. We went public last week.

GS: I thought that Artoon was started by [original Sonic Team member and Nights into Dreams director] Naoto Oshima?

RN: Ah - yeah. Ishii and Naoto Oshima. So now Ishii-san moved to be head of AQI, the holding company, while Naoto Oshima runs Artoon. Two guys started it, really.

GS: What was the reason to come together? Was it just to make a bigger presence for yourselves, or was it because of dissatisfaction with other publishers?

RN: Financially, Nakayama wanted to make his company public, but Cavia itself was too small to do that. He then asked Ishii-san if he was interested in joining. That's one thing. He also wanted to make the company a publisher, and to do that, since AQI was a new publisher, he needed a bigger presence.

GS: It’s a little different, but it sort of reminds me of ESP (AKA Entertainment Software Publishing, a support company for members of the Game Developers Network in Japan, including Treasure, Alfa System, Game Arts, Bandai and CSK, but mostly in terms of sales and PR).

RN: Oh, yeah! You're really familiar with the Japanese industry!

GS: I never really understood what ESP was doing. Was it a more loose connection than AQI?

RN: Yeah, I think so. In our case, three studios are 100% owned by AQI, so it's one capital. ESP was just a business deal with multiple companies.

GS: And then Game Arts bought all the shares, and they got the majority of their shares bought by Gung-ho. Anyway, I heard that Mr. Nakayama was funding and advising developers behind the scenes, even when he was doing the human resources company. I heard that he was influential in helping other people start studios too.

RN: Yeah. He's rich. Really rich. He started the company, and managed Cavia for a while, but then he left Cavia as a managing director, so what he's doing now is investment. He's not a board member anymore. He's just a majority shareholder of AQI now, but he doesn't participate in managing the company. He owns many other companies, and a lot of people come to him for consulting. If he finds those ideas interesting, and he funds those people.

GS: I was actually speculating that he might be funding Seeds, Clover Studio's reincarnation.

RN: Yeah, that could be.

GS: It seems like a lot of developers in Japan, especially big name developers like Tetsuya Mizuguchi and Atsushi Inaba at Clover are very dissatisfied with the current structure of Japanese gaming companies, because they all seem to be leaving to start their own thing. All the creative talent from Sega has left, for instance, except Yu Suzuki, but who knows what he’s doing. Why do you think that's happening?

RN: I used to work at Capcom, so I know why Inaba and Shinji Mikami – actually it was really Mikami - wanted to establish their own company. If a company becomes big and makes some big hits, the company grows. To keep a big company, they have to keep making a profit. To make a profit, a lot of effort goes into sequels for those megahits.

Also, when I was at Capcom, there were eight studios; it's interesting, because most of them left. Noritaka Funamizu (Street Fighter II and Monster Hunter Producer, now with his own studio Craft & Meister), Tsuyoshi Tanaka (who took over Funamizu’s position), Katsuhiro Sudo (spun out into a separate team by Funamizu’s group), Shinji Mikami (Resident Evil 4 mastermind), Tatsuya Minami (former head of Capcom Production Studio 1), Me, Yoichi Egawa (focused on mobile), and Atsushi Inaba (Clover Studio).

Shinji Mikami modern classic Resident Evil 4

GS: Did you get Okamoto in there?

RN: He was a manager. So back then, there was a portfolio balancing between those eight studios, and Mikami didn't like it. He felt as though he couldn't invent new things within Capcom's big organization, so he asked Okamoto to establish a different, inventive studio and do something creative. It doesn't have to be anything big, but he just wanted to do something more creative.

GS: Mikami doesn't seem to have formally left Capcom, according to some company statements. Is he with Seeds?

RN: He left. He's with Inaba, so he's with Seeds.

GS: Mikami is really impressive to me. When I played Resident Evil 4, for instance, I was really struck by how polished it was. It had an old style of gameplay, but felt really progressive.

RN: That's a good example. The things he creates are great, but that doesn't mean they'll be commercially successful. He was the one who chose the GameCube as the platform for Resident Evil 4, and from a business perspective, many people at Capcom don't think that was the right decision.

GS: How different do you find working in Japan versus working in the United States?

RN: It's very different. I feel like I've learned a lot from my U.S. companies. Back then in Japan, in the early '80s, you had to learn how to make games by yourself. There was no one there to teach you. It was your own learning, so I had my own style of making games. Then I came to the States, and I joined Broderbund.

They had a very sophisticated system, even for back then in 1988. They had a shared library, tools, multiplatform support, project planning, and project tracking. That was so new to me, and I learned a lot. I learned how to make games systematically, and I learned how to manage development teams - all in the States. I tried to apply those things I learned when I came back to Japan with my studio, and my team there, and it worked well.

GS: Do you think that there's more similarity between the two regions now than in the past, since that sort of interchange has been happening?

RN: It is (a bit more) similar, but still I think U.S. development is more planning-heavy, while Japanese development is more iteration-based. Japanese developers put a lot of time at the end into tuning or even scrapping things, but U.S. development is well-planned, so they make the game and finish it as-is. They don't like to scrap things at the end. If you plan it right at the beginning, that's great, but if your plan wasn't right, and you finish it, then it's done. In Japan they redo things a lot. It’s becoming similar though.

GS: What do you think it will take Microsoft to succeed in Japan, not necessarily financially, but in terms of really winning over the audience?

RN: Online. I don't know what's going to happen to PS3, so it’s (up in the air). Right now, in Japan, the Nintendo DS and the Wii are very successful, so many developers and publishers in Japan are focusing on the DS and the Wii, and very little on the PS3 and the Xbox 360. So eventually, most of the Japan-made games will be on either handhelds or the Wii.

They were ready to invest in the PS3, but the PS3 wasn't as successful as people thought, and it's expensive to develop PS3 games, so a lot of publishers now only do a couple of PS3 games, and many DS and Wii games. Then a little Xbox 360, because the 360 is successful in the United States. But its presence in Japan is small.

That was one of the reasons AQI started: to be uniquely positioned as a new publisher and developer. We invested heavily on 360, when no one else was doing that in Japan. We’re a 360-heavy company now. Back then, AQI thought the system would be more successful in Japan, but of course it wasn't actually successful. But, it turned out to be quite successful in North America, so our positioning is still OK. We make games for 360 not so much for the Japan market, but for the global market. Not many people do that.

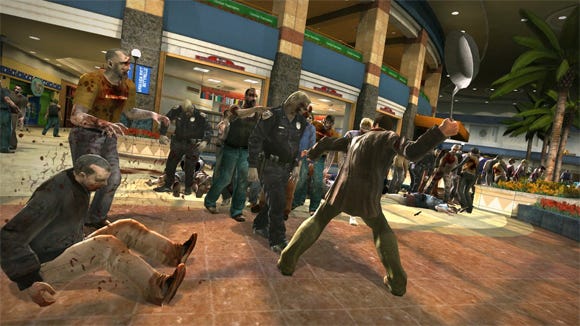

Capcom does that, and does it successfully with titles like Dead Rising and Lost Planet. But very few companies invest in the 360 and very few do PS3 games. So what I’m saying is that you'll see a lot of Japan-made DS and Wii games in the next few years, but very few high-end games from Japan. For those high-end users, they’ll have to buy more Western games, even in Japan. I think they will start to get used to Western games more, if they want to play high-end games.

Capcom's zombie action game for the Xbox 360, Dead Rising

I think most of the Japanese gamers will go to casual games on the DS and such, but there will be a high-end gamer market. For those gamers, because of a lack of Japan-made games, they're going to start playing U.S. games. Then, I think the Xbox 360 will have a better chance.

Also, gamers will start using the Internet functions. Xbox Live is so sophisticated – on that point I think even Sony is behind, even after their most recent announcements, like Home. I think their infrastructure is still behind. If Microsoft has a chance to succeed in Japan, I think the Xbox Live services and new entertainment fully using Xbox Live are important.

GS: When I was at the Tokyo Game Show last year, they were giving out Xbox Live cards, and I thought it was a great idea to get people interested in the console - but they were only worth 100 points each. And you can't buy anything with it!

RN: Sometimes they give away a little card, and it randomly chooses an Xbox Live Arcade game for free.

GS: Your comment about Japanese developers working mainly on Nintendo consoles is interesting, because I wonder if it will make the next-gen knowledge base build up slower in Japan. Is that a concern for you, for the industry's future in Japan? Or do you think Nintendo will be enough to sustain it?

RN: It’s a big worry. The gaming industry is global, so as long as the global industry is healthy, it should be fine. But if you consider the Japanese economy with the Japanese industry only, it's a concern. I think Japan will position itself toward more classic-styled games. It’s similar to how Korea and China (are known for) PC online games, and high-end beautiful games are done by American or European publishers. There will be a little bit of a positioning difference, but overall, I think the global gaming industry will be healthy. I think Japan will be very, very behind in terms of technology, though.

GSG: Capcom and Square-Enix are even licensing the Unreal engine now, so that makes me think that other companies are seeing the value of Western gaming now.

RN: Yes, and Lost Odyssey is using Unreal Engine 3 as well.

GS: Since you also worked there, why do you think that EA hasn't been able to succeed in Japan? Do you think that cutting their Japanese development staff was a good idea?

RN: EA is the only Western company that's surviving in Japan, so you could maybe say that EA is successful in Japan. But it's very hard for Western companies to succeed in Japan. I think it's all about perception, really. In the early days of the games market, Japanese games were pretty interesting back then, while many games from overseas were seen as being bad. Now, you'll find a lot of interesting and fun games coming from North America and Europe, but because of that experience that we have from the early 1990s, people tend to stay away from Western games.

I think there's a market for Western games in Japan, so I tried hard to bring those in. But still, pro-sports games are not popular in Japan. Somehow, they prefer Konami's Winning Eleven soccer sim series over EA's FIFA series, and they prefer Japanese-developed baseball sims as well. We have our own feeling for baseball, and American baseball games are very different. It’s really hard.

There were a few games that were successful, but (it’s all relative) even with the GTA series– it was successful but GTA III sold 300,000, GTA Vice City was 500,000, and San Andreas was probably also 500,000. So that’s very, very successful as Western games in Japan, but the sales numbers are still small overall. Interestingly, those games that sell over 300,000 units in Japan are pretty much all European-made.

Rockstar's controversial Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas

GTA was from Europe, and Tomb Raider was quite successful as well. When Sony first started with the PS1, they brought a lot of games to Japan, and some of them were very successful, like Formula 1. Interestingly, the basketball title that Sony released in Japan then was very successful, but that was done in France. That was weird. Crash Bandicoot was successful, and that's American-made, but it was done by Mark Cerny, who used to work in Japan. So his experience was different.

GS: And also Naughty Dog has Hirokazu Yasuhara, the original level designer from Sonic Team. He does all the level design.

RN: By the way, EA is very successful in the PC market in Japan. The PC market is different. It's very hard for Western companies to be successful on consoles in Japan, but in the PC market, the majority of games are from the West. But the PC market in Japan is very small. Right now, if you combine the PC and online market, it’s pretty big.

Online games are popular. But in terms of proper PC games, Age of Empires is very popular, and first-person shooter games are also popular – but on PC. So there are users who appreciate American games, but it’s more toward PC.

GS: Do the American games on PC sell for as much as Japanese games?

RN: Way more than that. Diablo sold 200,000.

GS: Oh, I mean price-wise. I know that when (Ys series creator) Falcom comes out with a new game it's always around 9,800 yen or so.

RN: No (they don’t sell for as much). The reason is that it's a gray market, so Japanese PC gamers import games from the States. Japanese versions would have to be comparable in price to other Japan-developed PC games. So it’s much cheaper to just import.

GS: It seems like there's more technological and creative innovation coming from the West right now than Japan, which is mainly focused on doing a lot of sequels now. It’s sort of the reverse of the old days. This could be because Western developers talk to each other more, and share ideas and techniques. What do you think about that?

Blizzard's hack-and-slash PC RPG Diablo

RN: I think you're right. As I said I’m worried about technology, Japan is already quite behind, and will be more behind. A lot of good technology is coming from the States. You have this kind of event (GDC). I was the founding member of CEDEC (Japanese development conference put on by CESA, which is akin to the ESA in the U.S.), and I wanted to make it the GDC of Japan, but CESA saw it differently. So it became CEDEC. It’s modeled after GDC, but it's very different.

Japanese people are not good at speaking. They are afraid of disclosing things, so all the sessions are very vague and generic, and all are sponsored sessions, or academic. I think Japanese industry people want to hear a lot of stuff from people who are actually making games, but they don't speak much, so all they hear is the academia or sponsored messages. It's not working that well. You have a very good culture here (at GDC).

GS: This is something I’ve been thinking about for a while, because when I was growing up, all of the best console games, for me, were done in Japan. There was this real creative energy. Now it feels like that’s changed. It seems like Japanese developers are so insulated, and isolated from each other, and aren't able to talk. I was speculating this is why they are leaving for other developers, so that they can have more open dialogue.

RN: Yeah. We do talk a lot though. The phone call I just got was from the president of Q Entertainment, Shuji Utsumi. I talk to a lot of developers doing the same genre (as Lost Odyssey). Microsoft is doing Infinite Undiscovery with Tri-Ace, and I talk to Tri-Ace a lot. We even talk about sharing technologies, tools, and even resources because it's a big project. I have a lot of resources right now, but now the needs of the resources are going down as we finish Lost Odyssey. Now that Tri-Ace ramping up people, we can lend some people to Tri-Ace or vice-versa.

GS: It seems like a serious problem that needs to be addressed. And I do think a magazine like Game Developer should be published in Japan.

RN: Yes, definitely. But you have a digital version now, so that would be pretty easy. I mean all you have to do is translate it, right? You just need a good translator.

GS: And good distribution. But that aside, how has work been going on Lost Odyssey?

RN: It's going really well. There were some troubles, but it's all fixed now, and it's going very well. We're finishing up the content-side. The biggest task is content creation for that kind of game. And it’s almost done - we're satisfied with the result, and it's going to come out this year. We have a few more months, so we still have time to polish things.

GS: What is your direct involvement?

RN: I run the company, and we have director Daisuke Fukugawa from Square Enix. He worked on Legend of Mana. We also have production managers to do content production. In terms of what they’re making, I am kind of hands-off. I try not to say much about what they are making, so all I am doing now is project management. They tend to add more and more stuff. It's fine if they feel it’s important, but at the same time, if it really is important, they have to think of ways to cut out things that are less important and lower priority. Those kinds of things. I feel like I'm still educating the staff. It's 120 people, so a lot of things happen.

GS: Do you have any examples of things you needed to cut?

RN: We had 400 levels we had to make, so some had to be cut to make others better. Characters are fine. We've got about 300 characters. There's a little more than seven hours of real-time cutscenes. We determine priority: there are A Cutscenes, B Cutscenes, and C Cutscenes. There were too many A Cutscenes - the ones where we make them really good. We had to reduce the number of A Cutscenes and make more B Cutscenes.

GS: Are they all real-time?

RN: Out of those seven hours, one hour is prerendered, and six hours are real-time. They don't really look different, though, it’s almost the same. The prerendered scenes are for better lighting and for more visual effects like explosions or when a tower falls down. We needed prerendering for those scenes, but characters look almost the same.

GS: I didn't know that it was level-based, or did you mean scenarios?

RN: We had about 400 locations, I mean.

GS: How long has it been in actual production development?

RN: Sakaguchi started discussions in late 2003, but actual production started in early 2004. Over three years ago.

GS: That was well before the technology was ready.

RN: Yeah.

GS: What is (Panzer Dragoon director) Yukio Futatsugi's involvement?

RN: Nothing. When I joined Microsoft, he was already there, making Phantom Dust. We started new 360 projects, and he was the last (original) Xbox project – so he was doing that. After finishing Phantom Dust, out of the six new projects we were working, on, five used outside developers. The only one that was internal was Lost Odyssey, and that was done someone else (other than Futatsugi). We didn't have any plans to do more than six, so Futatsugi became more of a game design consultant for those projects. He checks deliverables, and sees if they’re ok, and things like that.

He’s still doing that. I think he should start a new project, but that doesn't seem to be possible within Microsoft Japan right now.

GS: That’s a shame, because he’s always really impressed me with his work. There’s Panzer Dragoon obviously, Panzer Dragoon Saga was great. But I beat Phantom Dust too – and I don’t feel the need to beat games that often. He’s got a great style and vision.

RN: He should join AQI!

GS: Sounds good to me! Anyway, in a talk earlier, Sakaguchi mentioned that Lost Odyssey would be a mix of real-time and turn-based combat. Can you say more about that?

RN: Basically, it's turn-based, but we put some real-time flavor to it. It's more strategic than real-time action. The basic structure is turn-based - you walk around in the adventure portion, then you encounter monsters, and it comes to a battle scene. It’s not seamless – it’s adventure, then battle, then adventure, then battle. As you progress, there will be a lot of things you have to concentrate on in the battle scenes, and also you'll need to focus on timing. It's turn-based, strategic combat with some real-time features.

Microsoft Studios Japan's Phantom Dust for the Xbox

GS: Sounds like it’s a little bit old school still. So you're using the Unreal Engine with Lost Odyssey?

RN: Yeah.

GS: Is Microsoft Japan fine with using external tools?

RN: It was hard, because it was a new platform, and Unreal Engine 3 itself was in development, so we had to deal with incomplete middleware. We actually released a Lost Odyssey demo in Japan in November, though we finished it in June of last year. Back then, the Unreal Engine was still incomplete, so we had to release something on incomplete middleware. That was hard. I think that demo was actually the first thing that was released using Unreal Engine 3; it was before Gears of War! We had to do a lot of workaround for that. Now that they've done Gears of War, the engine itself is much more stable.

GS: You probably had to remake a lot of stuff after the demo, then.

RN: Yeah. The most difficult thing was communication. Everything is in English. They have Japanese support, but it's limited. All the good stuff is happening in the newsgroup, but that's in English, and my developers were pretty much all Japanese.

GS: How important is it for your employees to know English?

RN: I think it's very important going forward. Because as I said, we chose to position ourselves as a high-end production company, so we have to be competitive in terms of technology. All the good technology comes first in the States, so we have to be in real-time for learning those technologies. To do that, you need to be able to read English. So for technology guys (it’s really important), suddenly.

If any developers working in America would like to work on games like this in Japan, we welcome them. It's good if they can speak Japanese, too, I mean they have to be bilingual in order to work with Japanese teams, but also get updated information from the States.

GS: How closely involved is Sakaguchi with the Lost Odyssey development?

RN: Pretty close. It was very close when we were starting up the project. There was a Mistwalker office - which is a really small company, so it's basically just Sakaguchi. It’s like the Sakaguchi office. It’s like three or four people in that office. So we rented a big space next to Mistwalker for about ten people. At the beginning of the project, we sent those ten people in next to Sakaguchi's office and did initial work. He was writing the story while that was happening.

Now that things are going well, he's more hands-off. We probably see him twice a month. He lives in Hawaii, so he spends half of his time in Japan and half in Hawaii. When he's in Hawaii, he writes a lot. When he's in Japan, he does more producer-oriented stuff. He's quite involved, and I think he’s coming in again now that the game's playable. He'll probably come up with a lot more comments. We try and satisfy him as much as possible. That will take place over the next few months.

GS: I’ve been hoping that, on the Square-Enix side, we’ll hear from (Final Fantasy Tactics, Vagrant Story, and Final Fantasy XII original director) Yasumi Matsuno again. Maybe you should hire him!

RN: Yeah…but Sakaguchi is talking to him now, so I don’t know. He also started his own stuff.

GS: Right, but hasn’t announced anything, so it’s hard to know what he’s up to.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like