Q&A: Translating the humor & tone of Yakuza games for the West

"The humor of a_Yakuza_ game is a fine line to walk," says localization producer Scott Strichart in this in-depth chat about localization, the Yakuza games, and the ins and outs of Japanese humor.

Each of Sega's Yakuza games contains multitudes.

For example, Yakuza 0 (the series prequel released outside of Japan early last year) sets itself up as a playable crime serial set in '80s Japan.

But it can also be a cabaret management game, a blind date sim, a 3D beat-'em-up, an emulator of old Sega arcade classics, a rhythm game, a light-hearted RPG about solving stranger's problems, a real estate management game, and a surprisingly good place to learn the basics of tabletop games like shogi and mahjong.

From a developer's perspective, the scope of such a project seems daunting. From a player's perspective, it can be overwhelming -- my partner and I recently completed Yakuza 0, and saw that our 87 hours of combined play merited a "completion" score of roughly 33 percent.

The hook that holds together all these disparate game design elements, that pulled us and scores of Western players like us through the game, is the writing. For all its focus on cold-hearted criminals and petty evil, Yakuza 0 is a remarkably funny game; it affords players the freedom to quickly jump from incredibly serious, macabre scenes (a criminal is tortured in a warehouse) to (teach a shy punk band to act like Cool Rude Dudes in public).

That writing is translated and localized for the West by Atlus (alongside longtime series translator Inbound) starting with Yakuza 0 and continuing on through Yakuza Kiwami (a remake of the original 2005 game) and Yakuza 6. The localization of all three games has been overseen by Atlus' Scott Strichart, who recently sat down to chat about the ins and outs of adapting these games' humor and gravity for Western players.

It was an interesting conversation that went beyond the localization process (Atlus uses a translator/editor tag-team approach, rather than relying on translators alone) to touch on how, exactly, you translate humor, and how players in different regions can view a game or its characters completely differently. What follows is a version of that conversation we've edited for clarity.

The Yakuza games have a winning sense of humor. How do you translate that for a Western audience?

Strichart: The humor of a Yakuza game is a fine line to walk. It's very clear when the developers want to be funny. It's very clear to us when the writing that exists in the game is supposed to be like, "ha ha here's a joke." So we just want to make sure that if they intended for it to be funny, it also has to be funny to our audience. Whether or not that means changing the dialogue a little bit, changing the style in which it's delivered, making dialogue options a little bit more punchy, that kind of thing.

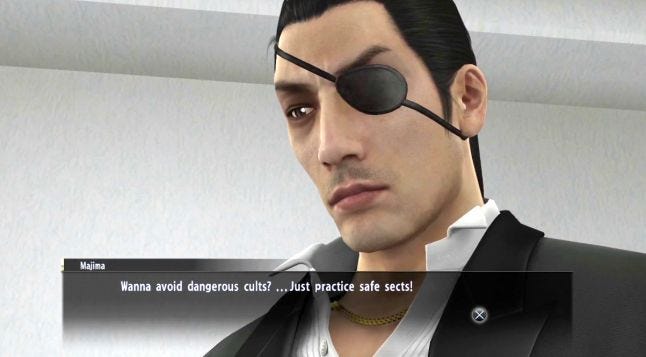

One of the perfect examples is, [in Yakuza 0] Majima encounters this...did you play the substory where he goes to infiltrate a cult? In that substory, one of the options he has is to crack a pun, in order to get this girl to snap out of her cult tendencies. So in Japanese, that pun is "futon ga futon da", which means "a futon is a futon" or, "a futon flies." It's a pun on words. It's basically a "why did the chicken cross the road" kind of joke.

If we literally translated that, it wouldn't work. If we put in "why did the chicken cross the road?" it's not much of a pun; it doesn't feel in line with Majima's character.

So that's where we had to come up with this pun that we ultimately went with, which was "how do you avoid dangerous cults? Practice safe sects!"

Okay, let's drill into that localization process -- how, exactly, did you go from a flying futon joke to a safe sex joke?

Well it wasn't just me -- we have a team of translators and editors who approach these games. These games are massive; if they were left to just me, i'd be buried under each of these games for years! Most of these Yakuza games actually are on par or greater than your average JRPG, in terms of volume of text.

How many lines of text were you working with in Yakuza 0?

Yakuza 0 is 1.8 million JPC (Japanese characters), and the average JRPG is, I think, 1 million to 1.2. So we were well above the average there.

So anyway, how our process works is, the scripts come in from Japan, and we divvy them up to certain translators and editors to make sure there's consistency among the sections that they're doing.

"We just want to make sure that if [the devs] intended for it to be funny, it also has to be funny to our audience. Whether or not that means changing the dialogue a little bit, changing the style in which it's delivered, making dialogue options a little bit more punchy, that kind of thing."

So that particular pun was in a substory, for instance, so the translation team who was on that was one of our outsourced translators, who was doing most of the Majima substories. Because they were familiar with Majima as a character, they were familiar with the substory content, and all that kind of stuff.

These kinds of localization issues, we don't know about them until we hit them. We're doing it line by line, and suddenly we're like "oh shit, here's a pun." And when you hit that, you have to take a step back and say okay, this isn't going to be a direct translation. We have to deal with it -- sometimes that comes down to a discussion amongst editors and translators, or sometimes a translator will flag it for the editor to say "I didn't know what to do with this, man. Let's talk about this."

So when that gets to the editor, the editor's job might be to come up with a way to make that pun palatable to the Western audience. That's generally the Atlus approach, is we use editors to refine the translated English text to make sure it makes sense to Western players.

A lot of companies don't do it this way. And it's not right or wrong, but a lot of companies dedicate a single translator who has the ability to translate Japanese to English, and make it good English. Whereas we use a method where the translators give an editor, not a literal translation, but translated words off the page that don't necessarily scream "this is great English." That allows an editor to come in and refine that text to make it palatable to a Western audience, whether or not that editor even speaks Japanese.

I really enjoy that style, actually. Back when I was the first localization employee at Level-5, it was kind of up to me to establish that style. I could have just thrown the work at a translation agency and let them go, but I thought it was a good idea to give it a more personal touch.

So we brought in a translator and, you know, when an editor meets a translator and they learn their style through working with them on a game or two, and you can almost feel their style through the text, you develop this like, symbiotic relationship with that translator. And that's kind of how I felt about that translator who was working on Attack of the Friday Monsters with me. It worked out really well.

So why do you think it's a good idea to use an editor/translator team, rather than just a single translator?

Well, it's not right or wrong. I think that both ways of doing localization have advantages and disadvantages. The advantages of this method are that it's a little more collaborative.

A translator gets to talk to an editor, and if you hit a line you're gonna stumble on, you can actually get a lot of insight into what that character is about, what they're saying, and kind of hash it out between you. If the editor kind of strays too far, the translator can kind of rein them back in and say "well, it's a little closer to the Japanese this way", and you end up refining a line to the point where it's a bit more accurate, or more true to what a Japanese developer was trying to convey. And that's something you can't get if you're just a single translator, a single mind trying to parse a game's text as best you can. There's no dialogue.

The second advantage is that, when editors are working on something, and they have less or no Japanese fluency -- I don't claim to have Japanese fluency -- we bring a creative writing aspect to these texts that might otherwise be just a direct translation. And a direct translation, that's not a localization. Not if you just translate something directly, that's often not enjoyable to read. It leaves humor behind, it ends up dry, it ends up boring to read.

What do you lose by using this tag-team method? Besides the extra costs, of course.

Here's the disadvantages: we're slower. When a game is translated, that's work that could be finalized, but then it then goes to an editor, who is then tasked with finalizing it. We try to mitigate that by making sure translators are going when editors roll onto a project, so you end up with this kind of lock-step process. But at the end of the day, it is a bit slower than if a single mind just translated the text and delivered it.

Is that why the Yakuza games seem to take a year or more, on average, to come to the West?

No, that is not why! [Laughs] We are closing the gap. That is my directive from management: "close the gap." Yakuza 5 was two years in the process, and that was because Sega literally closed their office up here [in San Francisco] and the project sort of stumbled out the door. 0 came back into our hands, once we'd established operation out of Atlus, and that took us, I want to say, a year and a half?

Kiwami was a little bit less, a year and two months. And Yakuza 6 was....a year? A year and three months? If you look at the past 6 months, where we've released essentially 3 titles, a Yakuza game every 6 months, no one else is accomplishing this. This is practically impossible. The fact that we're getting it done, with the quality level tht we're held to for this series, is a marvel for my team. I'm nothing but impressed with everyone's hard work on this.

Fair enough! What challenges have you faced along the way towards closing that gap?

To go back to that other disadvantage, on the translator/editor route. It's consistency. The more people you bring onto a team, the more people who touch it, the more likely you are to create inconsistencies. Amongst terms, amongst the way characters talk, amongst spellings, all of that stuff has to be mitigated. You have to have a strategy for that.

"The more people you bring onto a team, the more people who touch it, the more likely you are to create inconsistencies...You have to have a strategy for that."

What I'm talking about is like, this person is capitalizing the word patriarch. Or this person is using "jeez" with j instead of "geez" with a g. And you end up with a character that seems to speak in two different ways, or worse, you end up with literally different interpretations of a character.

When we did Radiant Historia, I decided that a character was going to have a little bit of a British lean in his voice. And I talked to the other editor about it, and even with that understanding...we ended up with completely different British leans! Because one of us understood cockney and one of us didn't.

And that's something that's now actually getting fixed. And you can mitigate some of that in QA, but those little miscommunications, if you don't have very strong communication amongst your group, especially as it grows beyond a couple editors and translators, these consistency problems balloon, and it has to be mitigated by a producer and/or a consistency pass on the text.

What advice would you give others trying to do something similar with their own games?

Focus on consistency and clarity. As a producer, I am the consistency pass. I am the voice on how characters should sound. I'm very upfront with my teams; we have daily standing meetings about our challenges that we're hitting, and we discuss these things upfront in terms-less meetings.

We try to frontload the localization as much as possible, with these meetings, with regular discussions to hammer out the fine details. And at the end, you know text goes through a translator, it goes through an editor, and then I act as a consistency pass.

With Yakuza 6, for instance, we rolled a new editor into writing the main story, and he didn't have a strong grasp of Kiryu's character. Until probably, halfway through the game. So in going back through his text, I end up tweaking probably 80 percent of the text. Because I'm a perfectionist. I shouldn't be doing it that much, but I do. And I told him, you know, your Kiryu's way stronger in the latter half than in the beginning. So I'm going to go back and kind of rewrite your beginning. And he was totally onboard with that.

Do you have any sense of how Japanese players perceive the Yakuza protagonists?

In Japanese, I feel like Kiryu is a little bit more of an avatar for the player. He uses a lot more ellipses than we do in the English version, because we actually want our audience to identify with Kiryu as a character. Whereas in Japanese, you might want to be like, I can put myself in Kiryu's shoes. I can be this Japanese badass.

It's a bigger leap to expect a Western audience to be like "ah, I can be this Japanese badass." So we give Kiryu a little bit more of his own characterization, that is very much in line with the Japanese when they do characterize him. So there's no gap there; it's just a matter of trying to bridge that gap Western audiences might face in trying to fully identify with a Japanese character.

How do you decide when to write in an original response, one that's not in the Japanese version?

When a Japanese person would know what he's thinking, because they're able to put himself in his shoes, or they might have a better idea of what's going through Kiryu's head, that's when we bridge the gap. When we decide okay, the player needs to understand a little bit more of what's going through Kiryu's head, because this isn't an immediately known quantity to them.

And Japanese storytelling can be very subtle, at times. And we don't want to be blunt and hammer players over the head with "hey this is what they're trying to say", but sometimes we do have to lead them a bit. We have to look at the text and be like, this is clearly trying to convey this subtle aspect of masculinity, or honor, because this is what these cultural signifiers mean. And then we have to present something to the player that makes it clear hey, this is a Japanese concept of honor, so please understand that through this thought process that Kiryu is having in the middle of it all.

What's a good example of that?

So, Majima's whole transformation from Yakuza 0 to Yakuza Kiwami. Longtime Yakuza fans know Majima is this class clown, kind of joker-esque personality. And when 0 [a prequel] came along, they decided to completely flip the script on this character [and present him very differently]. So you might get the idea that in playing through 0, Majima is going to be going kind of insane.

But that's not really the Japanese take on that. The whole point of 0 is not to show that he goes insane, but to show that he makes a conscious choice to...let loose. And it is subtle in the game, even despite our best efforts to be a bit more blunt about it, especially in the scenes with Nishitani [a loud, brash character] where it's clear Majima is gaining insight into how someone like that would live.

We brought that out a little bit more, specifically asking the devs "did you mean to communicate this?" Because even we were like, this is really, really subtle, guys. Were you trying to communicate a direct kind of correlation between Nishitani and Majima? And they were like, "yes. If you feel like you can bring that a little more obviously, without adjusting the text to the point that it doesn't make sense or it's not in line with the original, then go for it." And we did! And it's still very subtle. People, at the end of the game, they say well, Majima went insane. And it's like well, heh, let me show you the scenes where he didn't go insane, where it's supposed to be clear he made a deliberate choice.

How do you convey the nuances of the setting? It's the '80s, a period many players will only know from pop media, but it's the '80s in Japan as recreated by a Japanese team, replete with references to things like portable bag phones and stadium jumpers.

Right, we had to explain that he has this, you know the Japanese have these hybrid words, like stajun, the stadium jumper. So we we had to add something like, "in America you might call this a varsity jacket" because again, we had to bridge that gap. So now players can understand what the jacket is.

Same thing with the Yankee substory; we had to work in a bit of text that explains what a Yankee is, that subculture within Japanese punk culture.

How often do you check in with the Japanese dev team on this stuff?

If we have a clear direction, we just go with it. And if we understand it, we just go with it.

That said, there are obviously opportunities to talk to them, and places where we don't know, we need insight from them to understand what they wanted from the text. That happened a lot in Yakuza 6; there's a term that gets used a lot, a "Shangri-la" type term, where it could mean either a paradise, or a literal place in Tokyo. And we're like, which one did you guys mean by this? And they were like no, we were talking about the figurative type of paradise.

Going back to Yakuza 0, in the crossword puzzle section, the answers are nothing but gimmes until the last one, at which point it throws in this hard one: what's the difference between a sauce face and a soy sauce face? And we absolutely understood that Western audiences would not understand what that means.

At the same time, if there's no opportunity to explain it, we can also flip the script and make it a little educational. So no matter what option you pick, the consequences of getting that wrong are low; you might get a different item at the end of the substory. But regardless of what you pick, at least there's an explanation that makes it clear okay, this is a weird Japanese term to describe either a manly face or a soft, feminine face.

So how did your work on Yakuza 0 and Kiwami shape your approach to Yakuza 6?

Yeah. In Kiwami, one of the things that happens is that Shinji constantly refers to Kiryu as "aniki" in Japanese. And a literal translation of "aniki" is "big bro". But in the Yakuza, though, which is very familial, the ranking terms are literal family member terms. These dudes are your senior members, so they're your aniki. It's not meant to be literally, these are your big brothers.

But because that's a word so many people know, when we translated aniki as "sir", to indicate a deference, a respect, people were like "that's not what that means." I saw a lot of criticism for that. So in 6, the term aniki takes on a whole new level...there's a whole new section focused on this aniki thing. And we decided, you know what, since we've not really nailed it in Kiwami with "Sir", let's just use the word aniki. And we did that, and now it's in amongst the standard honorifics we use in 6.

It's Kiryu-aniki, now; Kiryu-aniki is a thing in this game. And there's not a whole lot of ways we could have worked in an explanation of what an aniki is, which led us to add an explainer in among the tooltips we implement on the loading screens. "Aniki means big bro, but in the yakuza it's a term of respect." And it's weird watching how Japanese language has become a little more common and ingrained in English lexicon over the years. So that some words which, ten years ago people would have said "what is that?", are now commonplace. Senpai, for example. Everyone knows senpai now. So we're pleased to be able to use that word, just straight up. Okay, this is my senpai.

Witness the power of anime. So I'm curious, was it tricky to localize the aspects of Yakuza 6 that deal with children? I gather a baby plays a key role in the plot.

Yeah, actually. This all goes back to Kiryu's backstory, because in Japan, an orphan has lower societal status than you might expect. They're nobody's kids, and they're not always given much respect. Because your roots play a bigger role there, whereas here (in the U.S.), whether or not you have parents, if you grow up to be something, that's who you are. The fact that you're an orphan doesn't necessarily follow you the same way it might in Japan.

So the fact that Kiryu is basically this surrogate father to Haruka, who has this kid, and then very early in the game he enters the hospital and is like, "I need to see Haruka." And they're like, "you're not her father." Or he's trying to prevent her kid from being taken by the state, saying "I'm basically her father, that makes this kid basically my grandson", and they're like "sorry bro." And that's not something we really had to localize around, because you as the player in the West, at the end of the day you can understand that okay, the state is coming for this child. And this is how Japan is treating Kiryu, and Haruka, and the child. They're breaking up this family. And that plays into some of Kiryu's decisions.

That's part of the virtual tourism I think Yakuza offers; you get to see how Japan as a country would handle this situation, and where this former yakuza, his surrogate daughter, and her son would fit into the system.

Sorry, "virtual tourism"?

Part of what Yakuza offers, to even the Japanese audience, is an inside look at things like the nightlife industry. An these are real problems that the nightlife industry faces. Not every guy's a creeper, but there's obviously those occasional instances where a guy will cause a scene at a hostess club, and a manager has to come deal with it.

That's what the appeal of this series is to people, wherever you are, you don't necessarily have insight into what these worlds are like. Haruka's entire chapter in 5, as an idol, where you really get to look behind the curtain of what it means to be an idol, an what you have to give up, for example.

You mention that in Yakuza, you're not doing a lot of crime. This all comes back to a localization decision too, because back in the first game there was a decision on the part of the localizers, that you know "oh this looks like a crime game, they are doing crimes, this is about the yakuza. Let's call it Yakuza." When the Japanese name of the series is "Ryu ga Gotoku", which is "Like a Dragon."

And now that we've really come full circle and realized these games are the journey of Kiryu, not the journey of the yakuza....perhaps these games are misnamed. But you can't throw away nine years of brand integrity just to rename your game, so it's a battle we have to constantly face. That Yakuza is context, not content.

Do you think Kiryu and Majima are perceived the same way in Japan as they are in the West? As basically good-hearted mobsters?

With subtle differences, yes. The goal is to make these dudes likable, and aspirational. In Japan, part of what Kiryu's arc represents to a Japanese player is the ability to change things. The ability to make an impact, and to decide that something is right, and follow the path to make things right. Despite how hard it is.

And maybe that's not what a Western player gets out of Kiryu. Maybe they just see Kiryu as this strong, honorable man. Because here in the West, our culture says of course you can change things, regardless.

Earlier you mentioned that these games are huge undertakings. How do you avoid burning out anyone on the team while localizing them?

We're very conscious of schedules. And when things look like they're falling behind, we can always add to the team, with people who know the franchise. At this point I've cycled in half the office onto the Yakuza titles. And I act as the consistency, as the glue.

It's tight, I'm not gonna lie. But I go home at night, and that's part of making good schedules, and being a good producer.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)