Postmortem: Bitesize city-builder, The Block

How one developer created a publishable game in four weeks.

Game: The Block

Developer: Paul Schnepf

Publisher: Future Friends Games

Release Date: 16/12/2022

Platforms: Steam

Number of Developers: 1

Length of Development: Four Weeks

Development Tools: Unity, Blender, Cubase

What’s the minimum amount of time a single person needs to create a market-ready video game? I decided it was four weeks. That was in May last year. I was just about to head into the next project with Grizzly Games, the small indie studio I co-founded. The project had a yet unknown scope and was bound to kick off in, you guessed it, four weeks.

Suddenly a weird anxiety hit me. I wouldn’t publish anything for who knows how long, depending on how the new project went. I wasn’t even sure exactly why this made me anxious. But I was determined to create something publishable in four weeks. No matter what. And that’s how I began development of The Block.

Hyperminimalism, or in other words, I suck at game design

The Block turned out to be a very minimalist city-building toy. However, this is not what I thought I was about to make when I started it. Initially, I wanted to create a much more traditional game. In half a day I prototyped a thing where you would place randomly sized and colored blocks on a square play area. In hindsight I can’t say why I did that, it was just something that felt organic to me. The idea was to make some kind of little procedural puzzle game–like Tetris but without falling shapes and the time pressure, and on a plane.

You might be able to tell from that description that game design isn't my greatest strength. I'm good at efficiently and thoroughly developing a vision, but I struggle when it comes to designing the intricate details of game systems. I actually thought this little project would help me hone those skills, but as you’ll soon learn, I’m not sure whether it had the desired effect.

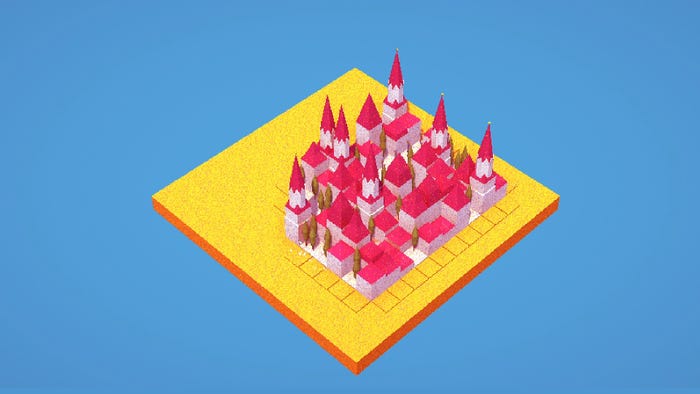

For instance, I couldn't really think of engaging rules for my game, but I really enjoyed placing these colorful, different-sized blocks. Mainly because I liked how they created these little city-like structures. At that point, I paused and thought "Why not make a little city builder?" It’s a genre that’s endlessly fascinating to me, and I figured that would make it easier to come up with proper mechanics.

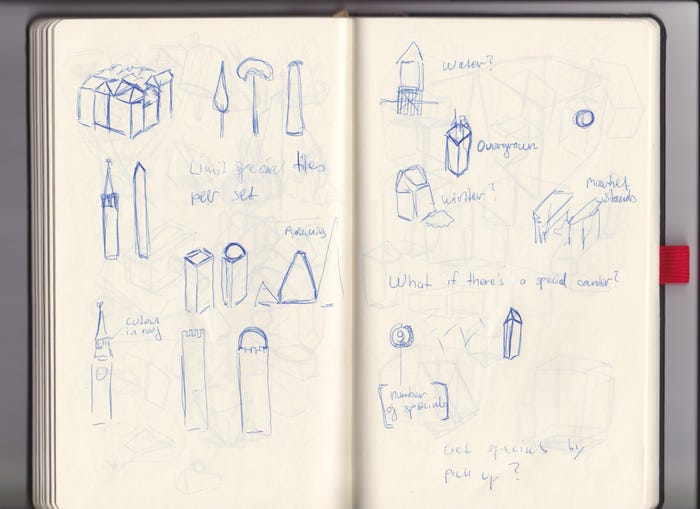

Early concept sketches for The Block

I was wrong. Giving the little blocks some roofs spawned all sorts of gameplay ideas in my head, but they were mostly just mechanics from other city builders I’ve played and I didn’t want to just merely copy something. Simply placing the blocks was still kind of fun, though. In a moment of desperation, I decided to just throw my weight behind that lone mechanic. If I was having fun meditatively placing little houses on a square, why wouldn’t other people enjoy this as well? Maybe this could be a digital toy, just like The Ramp was–but even more minimalist. It would simply allow players to lose themselves in the experience of creating a small city for a couple of minutes, without all the restrictions and mechanical considerations that are usually involved.

From there on out, I scrapped everything else and focused on one thing: making the core gameplay feel as good as possible. Obviously, how much fun you’d have playing would mostly depend on the atmosphere, so for the remaining two weeks I set about implementing sound design, polishing the UI, and modeling some slightly more detailed buildings.

Future Friends to the rescue

So, I've talked plenty about the prosecution behind The Block, but what about getting it published? I'd initially planned to self-publish, and given the size of the project the prospect of bringing a publisher on board seemed laughable at best. But I eventually decided to reach out to Future Friends Games, an indie game PR agency I’d worked with on my previous title, The Ramp. They did a fantastic job last time, and I wanted to hear their thoughts on The Block. Mainly, I wanted to know whether they felt it was worth doing any marketing for something so small.

It turned out they were not only interested in doing PR for The Block but also in publishing it (besides offering amazing PR services, they have published a couple of sweet indie games like Omno or Exo One). We agreed on keeping the original scope and treating the whole thing as a little experiment. I didn’t even think about that opportunity when reaching out to them, but it was exactly what I needed. With someone else handling all publishing-related tasks like setting up a Steam page, creating a trailer, and many other things, I was able to focus on actually finishing the game in what little time I had left.

Rapid, but unsustainable, development

Because we’d been looking for a timeframe that wasn’t too busy with other titles, the release took place about six months later in December, but the game itself was 99 percent complete at the end of the original four-week development period. Usually, I take great care to maintain a healthy work-life balance, making sure not to crunch. With The Block, however, I kept a pace that would surely not have been sustainable long term.

The finished article

Honestly, I don’t think there would’ve been any other way to finish the project. In this specific case, I also don’t think it was a bad thing. Obviously, you shouldn’t try to run a marathon at a sprint pace, but for its own sake and knowing it was only for this very short distance it was a lot of fun. The whole development felt like one long game jam instead of actual work.

Decision-making, something that drains a lot of energy in regular projects, became a very lightweight process. I had to skip all the "move ideas in your brain for hours on end" stuff and just go with whatever popped into my mind. That resulted in a general state of flow, and as a consequence work on the project felt less exhausting than usual.

A warm reception

Overall the game was warmly received–something I’m very grateful for–and I was surprised to see rather large outlets like PC Gamer and Kotaku covering it. On the other hand, it definitely failed to take off in the same way as some of the titles I’d previously worked on. In its first month, The Block sold roughly 7,000 units, grossing around $15,000. For four weeks of toying around I’d still count it as success, but nevertheless, I’d like to take a look at what, in my opinion, would have been necessary to make The Block a better product.

What was the most frequent complaint? I think many players felt the positioning of buildings should hold more meaning. Achieving that wouldn’t necessarily mean increasing the scope or pursuing more traditional mechanics. I believe there’s great potential in the concept of the digital toy. Take Oskar Stålbergs, Townscaper, as a wonderful example. I believe the source of joy in playing with toys stems from exploring the various possibilities they present and ultimately finding meaningful goals within that space. This is where The Block falls short. Beyond the meditational aspect, there is little to explore, and the game’s possibility space doesn’t allow for players to set many personal goals. I’d look to expand that aspect of the project in a bid to improve the overall product.

Conclusion

It’s been a ride. I had basically no expectations for The Block, with it mainly being an experiment and a challenge to myself. Still, there was an interesting and unexpected takeaway for me:

After the moderate success of my last solo project, The Ramp, I was paralyzed with anxiety for a while. Would the next thing I was creating live up to its predecessor? Would I meet people’s expectations? Would people expect me to only make skateboarding games now? Would they be angry if I did something else? Obviously, people are usually busy minding their own business and nobody is that interested in what you’re up to anyway. Writing those fears down now I can laugh at myself, but they felt very real at the time.

When working on The Block, the super-narrow timeline I imposed forced me to stop caring about all those things. Focusing all my energy on producing something publishable while at the same time not harboring great expectations for success certainly helped to get rid of that creative block (haha).

Overall, it’s been great fun and a really welcome variation to my usual work routine–I can highly recommend trying it sometime. After all, with a timeframe of four weeks, there’s very little to lose!

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)