Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In his latest 'Persuasive Games' column on sociopolitical games, designer/author Ian Bogost analyzes the 'vignette' that is Hush, a student game which movingly chronicles the massacres of the Rwandan Civil War.

[In his latest 'Persuasive Games' column on sociopolitical games, designer/author Ian Bogost analyzes the 'vignette' that is Hush, a student game which movingly chronicles the massacres of the Rwandan Civil War.]

Hush is an unusual game created by University of Southern California Interactive Media Division MFA students Jamie Antonisse and Devon Johnson in their fall 2007 Intermediate Game Design and Development course.

Like Darfur is Dying, created by fellow USC IMD student Susana Ruiz, Hush creates a personal experience of a complex historical situation. Ruiz's game addresses the contemporary crisis in Darfur; Hush's inspiration is another genocide, the 1994 slaughters of the Rwandan Civil War.

Darfur is Dying is part role-play, part simulation. First the player takes the role of a displaced Darfuri child trying to retrieve water while avoiding Janjaweed militia patrols. If successful, the game becomes a management game, in which the player must uset the water to grow crops and assist hut builders.

Even though the camp management game bears much more similarity to existing game mechanics -- using resources and time wisely -- the water fetching part of Darfur is Dying feels far more effective as a game about genocide.

The game offers a zoomed-in, personal experience that characterizes one aspect, albeit simplistically, of one aspect of lived life as a refugee. The management game's social rationalism betrays the sense of emotion portrayed in the water fetching game.

Antonisse and Johnson surely knew of their forerunner's work. Hush avoids Darfur's mistake, its creators choosing to focus on a singular, personal experience as a solitary approach to the topic of genocide.

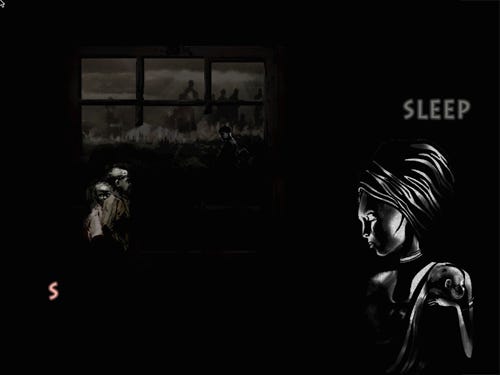

The game is about a Rwandan Tutsi mother trying to calm and quiet a baby to avoid discovery by Hutu soldiers. Its gameplay attempts to simulate patience. It's a rhythm game, but one that demands slow response rather than the fast action of Dance Dance Revolution or Guitar Hero. Letters corresponding with words of a song fade in and out. Pressing the correct key at the apex of brightness registers a successful soothe. Pressing too early or too late fails to calm the child, and his crying increases.

Hush is a short game; it takes around 5 minutes to play, maybe longer for players who take a while to acclimate in the how-to at the beginning. Allowing the child's crying to increase too much alerts a passing Hutu patrol, and the screen fades to red, a not-so-subtle implication of the pair's bloody end. Successfully working through each "level," which corresponds with a word of the lullaby, ends the game, as the Hutu patrol passes.

The ambience of Hush is created primarily through aural and visual ambience. Whether by design or by accident, the overall aesthetic of Hush bears some resemblance to other titles that have come out of USC Interactive Media, especially flOw and Cloud.

Hush and Cloud share the use of illustrations and broadcast-style motion graphics as a stage setting tool, although the former uses them in-game rather than as preface. Well-crafted, stylized renderings of documentary imagery and sounds from Rwanda of the early 1990s give a sense of the time and place. Oddly, the static woodcut-style image of mother and baby are the only figures that remain static throughout the game.

In literature, poetry, and film, a vignette is a brief, indefinite, evocative description or account of a person or situation. Vignettes are usually meant to give a sense of a character rather than to advance a narrative.

They are frequently impressionistic and poetic, even if rendered in prose or visual form, a tendency reinforced by the term's secondary meaning in photography: a loss in clarity or brightness at the edge of an image due to the occlusion of a lens's circular optics on square or rectangular emulsion.

In writing, the vignette is a literary sketch. The House on Mango Street, Sandra Cisneros's collection of poems and stories about an adolescent Hispanic girl coming of age, offers one example. In film, vignetted style can be found in Robert Altman's Short Cuts, which offers detailed, sordid glimpses into the lives of residents of Los Angeles.

Altman tends to create narrative dependence between vignettes, a feature not found in the Raymond Carver short stories from which Short Cuts was adapted. Other films, like Grand Canyon and Magnolia, also use this style.

The vignette is neither essay nor documentary. It does not make a direct argument, nor does it rationalize. It depicts, roughly, softly, subtly.

As an aesthetic, the vignette is surely underused in video games. One reason might be the relative rarity of small-form representations of human or natural experience in games. Minigames like those of the Wario Ware series are not vignettes; they do not lightly paint a sense of an experience or character; rather, they overtly depict mechanics thinly gauzed in a fictional skin.

The small-scale experiences of casual puzzle games like Zuma are too abstract and unremitting to sketch a particular experience. When larger-scale commercial games attempt similar goals, they typically do it through narrative techniques like cinematics, as in the cutscenes of Final Fantasy VII (pictured below), or artifactual evidence, as in the found recordings and notebooks in BioShock.

One could argue that the visual, aural, and mechanical abstraction encouraged by the technical constraints of early video game platforms like the Atari VCS verge on vignetting their subjects. Warren Robinett's Adventure for VCS renders labyrinths as playfield mazes and the hero as an unembellished dot created with the machine's ball graphics register.

But abstracting is different from sketching; the former tries to get to the essence of an experience or a system, while the latter tries to trace its uniqueness.

Hush offers a glimpse, as it were, of how vignette might be used successfully in games. As an exploration of the potential of the style, the game is a success. And as a vignette of a situation in mid-90s civil war-torn Rwanda, the game is compelling, if perhaps simplistic and overly mawkish.

The anxiety of literal death contradicts the core mechanic's demand for calm, but in a surprising and satisfying way, like chili in chocolate. The increasingly harsh sound of a baby's cry that comes with failure attenuates the player's anxiety, further underscoring the tension at work in this grave scenario.

But as a depiction of patience and child comfort, the more abstract experience actually created in the gameplay, Hush falls down somewhat. Patience as a game mechanic is a promising idea, but Hush's implementation of it is far too regular, too methodical and mechanical to encourage that sensation.

Breaking down the words of a lullaby into individual letters to be input effectively destroys the rhythm of singing a real lullaby, replacing the smoothness and gentleness of that activity with Sesame Street letter concatenation. Furthermore, each letter transitions to full glow in the same amount of time, so one straightforward way to play the game is just to count a rhythm and then execute the keypress at precisely the right time.

The jerky eye movement required to scan the screen for the appearance of the next letter in sequence likewise betrays the calm, slow movements of comforting a child. The literary aphorism "write what you know" is surely overused, but one wonders if these budding student developers have any firsthand experience rocking a child to sleep.

Taking a lesson from Cisneros, vignettes in any medium become most powerful when they bring out the subtlety and distinctiveness of individual experiences.

Several structural elements that bookend the game further spoil the its vignetted style. The first is the tutorial, a short level the player must pass successfully before beginning the game in earnest. The fictional context for the mechanic is only introduced after this tutorial, and the mechanic is hard to perform accurately at first, making the experience feel arbitrary.

The second is the game's concluding statement. Video games about difficult or controversial topics run the risk of drawing criticism for their concept alone, even if the execution is thoughtful and sensitive. A disclaimer of sorts appears at the end of a successful run of Hush. It is respectful and thoughtful, anticipating possible objections to the very concept of a game that addresses the Rwandan genocide.

I appreciate why creators wanted to hedge a bit here, but doing so at the end of the game rather than the beginning does little framing work for the video game illiterates who really need it.

Moreso, the disclaimer offers an unnecessary explanation of an experience that needs to stand on its own for its full aesthetic power to come to bear. Perhaps if it read like epigraph rather than moral this textual punctuation would integrate with the rest of the game more fluidly.

But perhaps the most bothersome structural sabotage is wrought by the splash and end screens that USC appears to demand its students include in their work. The film-credit style announcement "USC Interactive Media Presents" that begins the game is contradictory to the vignette.

The overt copyright notice and both USC and GarageGames logos that precedes these credits infects the game with an unwelcome foregrounding of the legal moil surrounding students' rights to the work they create at universities.

These lessons issue a challenge for future vignette-styled video games. The vignette, it would seem, runs somewhat contrary to the conventions of high-polish user-centered production.

The cinematically-influenced splash screen, the process of slowly introducing game mechanics, and even the commercial packaging of video games as commodities risk overpowering the delicate aesthetic of the vignette. This is a powerful representational mode for computational expression, but one whose mastery lies in the future.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like