Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

The invention of Kodak's Brownie made photography accessible to everyone, and Ian Bogost asks whether the era of user-generated content opens doors for games as 'snapshots.'

In the late 19th century, photographs were primarily made on huge plate-film cameras with bellows and expensive hand-ground lenses. Their operation was nontrivial, and required professional expertise.

The relative youth of photography as a medium made that expertise much more scarce than it is today. All that changed when Kodak introduced the Brownie Camera in 1900.

The Brownie was different. It was about as simple as cameras get: a cardboard box with a fixed-focus lens and a film spool at the back. It took 2 1/4 inch square photos on 117 roll film, which George Eastman had first used a decade earlier.

Millions of Brownies were sold through the 1960s. The simplicity of the camera made it reliable, and its low cost (around $25 in today's dollars) made it a low-risk purchase for families or even children.

Both camera and film were cheap enough to make photography viable. Easy development without a darkroom made prints possible for everyone.

The Brownie, and later the 35mm camera that replaced it, didn't just simplify the process of making pictures; they also ushered in new a new kind of picture: the snapshot. Snapshots value ease of capture and personal value of photographs over artistic or social value.

The Brownie brought photography to the people, but not without some help. The snapshot concept was borrowed from a hunting term for shooting from the hip, but Eastman contextualized the act for the masses.

For its advertising, Kodak coined the "Kodak moment" and encouraged photographers to "celebrate the moments of your life," as they still do today. Eastman's promise was "You press the button and we do the rest."

What if something similar were possible for games, a sort of video game snapshot?

More than a century after Eastman's simple roll cameras, today's computer culture values a similar strain of creative populism. Websites and software provide tools that promise to "democratize" the creative process.

Cheaper, more powerful hardware and inexpensive, easy-to-use software have made professional video editing and DVD production available to everyone. No-investment on-demand printing have made CD and t-shirt manufacturing a snap. Blogs and one-off book printing services have made written publication easy.

Following this trend (and its commercial success) are several nascent attempts to do for video games what the Brownie did for photography. Big players like Microsoft (Popfly Game Creator), and EA (Sims Carnival) have gotten into the game-maker game, as have start-ups like Metaplace, Gamebrix, PlayCrafter, and Mockingbird.

Microsoft's Popfly service

Areae's Metaplace

Each of these products offers users a slightly different way to simplify game creation. Sims Carnival offers three methods: a wizard, an image customizer, and a downloadable visual-scripting tool. PlayCrafter relies on physics, Gamebrix on behaviors, Mockingbird on goals. Popfly uses templates.

As platforms, each tool relies on the formal properties of different sorts of games. Some differences are obvious: Sims Carnival's Wizard and Swapper tools let people create games very easily by changing variables and uploading new art, while PlayCrafter automates physical interactions.

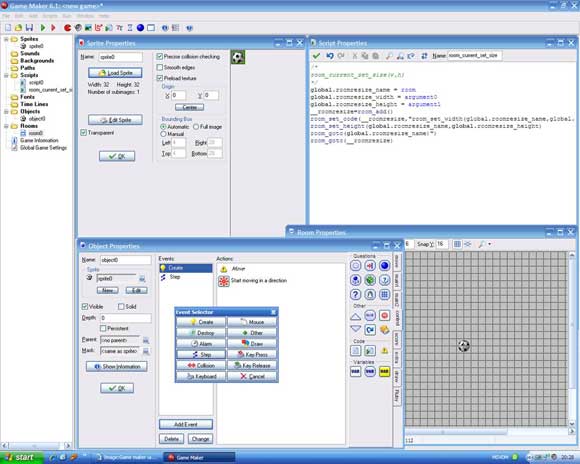

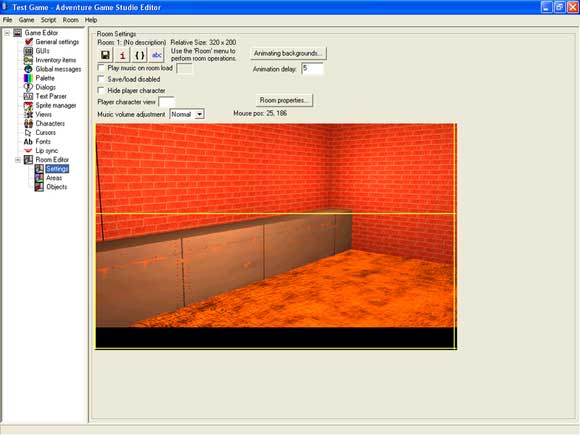

Formal distinctions are a common way of simplifying the creation of games. Long before Sims Carnival and its brethren, desktop game creation software used genre conventions as the formal model for add-assets-and-script type tools: GameMaker fashions tile-based action/arcade games; Adventure Game Studio makes graphical adventures; RPGMaker outputs role-playing games.

GameMaker

Adventure Game Studio

A focus on formal constraints like character statistics or genre distinctions like moving from screen to screen makes sense from a tool developer's perspective: different sorts of games require different kinds of programmatic infrastructures.

But from the lay creator's perspective, genre is a less useful starting point than topic. "I want to make a game about my cat" is a different sentiment than "I want to make a graphical adventure game." Photography doesn't make such a distinction; a camera can just as easily take a landscape as a portrait.

A fundamental difference between Eastman's Brownie and today's DIY game tools emerges: game creation can never be an automated process. Taking a photograph is easy partly because so much of the process goes on without us. After you press the button, light bends through a lens onto the emulsion of a film or the light-sensitive surface of a CCD.

Development can be outsourced to Wal-Mart and digital images are ready for immediate printing or posting. Video is similar; editing, titles, and sound are all optional but easily added with tools that come with every modern computer. Writing isn't automated like image-making is, but it 's a skill everyone uses in their daily lives; it's the printing or publishing that's better facilitated by new tools.

Conversely, video game creation exercises few common skills. It requires programming of some kind, or puppeting a tool that does the programming for us. It requires animation, sound design, and environmental design.

It requires designing for interaction, which can be complex even when the result is simple. It requires careful tuning even just to produce an experience that functions, let alone functions interestingly. There is simply no magic box we can put in front of the world which, when a button is pressed, turns what it sees into a video game.

People were already fairly accustomed to using and creating images, video, and writing before the social web came along to make it easier to distribute them. That doesn't mean people were creating good images, video, and writing: just think of the last time you sat through someone's child birthday party video, perused their family photo album, or read the soddy poetry from their courtship.

The reason other people's cherished objects are just crap to you, to borrow a line from George Carlin, is because they have invested them with sentimental meaning. A snapshot has value only for the very few, even if it can be shown to the many.

This is a principle many portrayals of web 2.0 misunderstand. The so-called long-tail economics of web aggregators make a business out of offering high-quality content for everyone, low-quality content for no one, and everything in-between.

Despite the tabloidesque tales of ordinary people made YouTube stars that litter popular magazines, the fundamental benefit of simple creation and publishing tools lies in their ability to let people make things for one another on a very small scale, one traditional marketplaces can't sustain.

And what are the things people tend to make first, for the smallest audiences? Personal things, things that speak between themselves, and their friends or family. Snapshots, of a variety of sorts. All of those millions of photos or videos or blogs about vacations or pet tricks or hobbies add up.

The outcome of such work isn't important because it's good; it's important because it holds meaning for its creators and their kin. No matter what the VCs and technopundits may say about sharing and aggregation, YouTube and Flickr and the like function as social media because they function first as private media. Our notion of "private" has just expanded somewhat.

If you look closely at sites like Sims Carnival, you'll find the snapshot games hidden among the much less interesting DIY attempts at mainstream casual games. Games about crushes, games celebrating birthdays, games poking fun at celebrities. That site even has an "e-card" section for such games, and premade templates to create games about kissing a date, icing a birthday cake, or celebrating the holidays.

Sims Carnival's tools make the customization process more like Eastman's "we'll do the rest." It's easy for someone to insert fixed assets like text and images -- the things they already learned how to create easily in previous eras.

The most successful snapshots on Sims Carnival are not good games compared to casual games, and it's wrongheaded to compare the two. Rather, the successful snapshots are good games for their creators and those with whom they might share their efforts.

Consider a particularly telling example, Dad's Coffee Shop. The game was created with the Swapper tool, by replacing a few assets from the stock game Fill the Order, a simple cake shop game. The gameplay is identical; the player drags the correct cake to match a passing customer's request.

Dad's Coffee Shop's creator has added occasional photos of her parents, and this important description: "In loving and respectful memory of my father who never met a stranger." Like a snapshot, the game has value because of the way it lets its creator preserve and share a sentiment about her family. Likewise, you and I can appreciate it not as the crappy casual game that it is, but as the touching personal snapshot that it also is.

Or consider You're Invited to go to heaven, a simple quiz game created in Sims Carnival's Wizard tool, which asks a series of step-by-step questions to generate a game. You're Invited is a rudimentary example of Christian evangelism.

The game poses just a single question, "Who is the Lord of your life," and offers four answers: Chris Brown, Orlando Bloom, Zac Efron, and Jesus Christ. The "correct" choice is obvious, and it's tempting to write off this game as trite, even worthless.

Its single question would seem barely to qualify it as a quiz game, a genre itself on the very fringes of the medium. But there is something deliberate and honest about its simplicity: this is not a game meant to inspire conversion or even head-scratching; it's just a little touchstone in someone's day for reinforcing what's really important to the believer.

The game somewhat resembles the inspirational photo or message pinned to a refrigerator or carried in a wallet. It serves a simple function: to remind its player that God, not an entertainer, is worthy of worship.

If You're Invited to go to heaven offers a modest critique of the sea of media fandom, plenty of other snapshot games on Sims Carnival do just the opposite, celebrating a favorite personality cult. Lately, a popular example is teen idol Joe Jonas, who has found his way into a number of Sims Carnival games. One popular exmaple is Wash Joe Jonas, a variation of a dog-washing original created by Sims Carnival staffers.

As with most snapshot games, gameplay is quick and almost meaningless on its own: the player moves a mouse frantically to suds up Jonas before time runs out. Its purpose is simple and obvious: it offers a simulation of an intimate (if weird) relationship with a pop icon, one the player is unlikely ever to experience in real life.

The game functions like a wall poster or a printed notebook, or even like a Photoshop job that inserts teen beside heartthrob. When played, the game works as a kind of snapshot effigy, a thing to create sighs and coos and then to be put down again.

"Democratization" is an awfully haughty way to describe new ways of using old media, but it's a term you often hear among the Internet elite. Eastman's cameras were "for the masses," like the Model T., and web services like YouTube and CafePress certainly are as well.

But whether or not they deserve to be confused with self-governance and citizenship is another matter. Silicon Valley's perverted libertarianism has conflated technological progress and social progress. Another conception is needed.

There are lots of things one can do with web-based game making services. One of them is to try to create hit games that generate ad revenue and earn public renown. Another is to create art games meant to characterize the human condition, like I recently tried to do with the Sims Carnival Game Creator. But perhaps the most interesting uses of these tools are the informal ones that so closely resemble snapshots in spirit and function.

Some inventions, like the Brownie, make a previously complex creative process much easier. Yet the Brownie alone did not invent informal photography. It was just a tool. People had to be taught how to use it, which Kodak did through a lot of hand-holding, careful marketing, and patience.

Such is the next challenge for the video game snapshot. In this respect, the Sims team's effort to seed their site with examples for remix is an admirable start. The problem is, they are examples that aspire a little too much toward real casual games, a notion reinforced by the site's traditional genre categories (action, adventure, racing, shooter).

The Brownie teaches us that snapshots aren't just good pictures created easily thanks to simple tools. They are also good pictures -- or games -- created for different purposes. The future of video game snapshots will require platform creators to show their potential users how to incorporate games into their individual lives.

The result could be very important. The snapshot didn't just popularize photography as chaff, it also helped more ordinary people appreciate photography as craft. The successful game creation platform will be the one we can say the same of, someday.

[Brownie photograph, by Håkan Svensson, used under GFDL.]

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like