Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Ian Bogost looks at Quantic Dream's Heavy Rain in the context of film and cinematography's history to explain why he feels the game, billed as an "interactive film," is not quite that.

[Ian Bogost looks at Quantic Dream's Heavy Rain in the context of film and cinematography's history -- including spoilers for the critically acclaimed PlayStation 3 game -- to explain why he feels the game, billed as an "interactive film," is not quite that.]

Heavy Rain is not an interactive film.

I know that's what its creators were after, and I know that's how it's been pitched to the market, and I know it's been critiqued as both a successful and an unsuccessful implementation of that goal.

To understand why the game is not a playable film, it's important to review what makes film unique as an art form. There are conflicting opinions, of course, but one stands out: film is editing.

Soviet filmmaker and theorist Lev Kuleshov first suggested editing as film's primary quality.

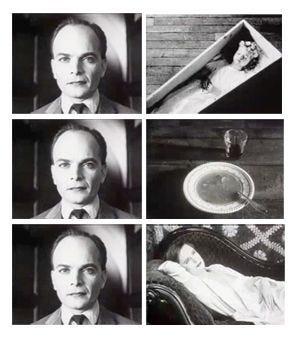

His well-known "Kuleshov Effect" seemed to prove the point: in the experiment, Kuleshov cut between the expressionless shot of a famous Russian silent film actor (Ivan Mozzhukhin) and a variety of other shots: a young woman reposed on a chaise, a child in a coffin, a bowl of soup.

Even though the shot of Mozzhukhin's face remained identical with each cut, the audience made different assumptions about the meaning of his expression.

Kuleshov's influential pupil Sergei Eisenstein believed it too, arguing that editing techniques (particularly montage) made it uniquely possible for cinema to link seemingly unrelated images through juxtaposition.

The Soviets weren't alone in their reverence of editing. D.W. Griffith's early work made strong use of editing and cross-cutting, for example. And as the years and then the decades passed, editing only increased in importance. Stanley Kubrik adopted Kuleshov's position more or less directly. Francis Ford Coppola has said this about the practice:

"The essence of cinema is editing. It's the combination of what can be extraordinary images, images of people during emotional moments, or just images in a general sense, but put together in a kind of alchemy. A number of images put together a certain way become something quite above and beyond what any of them are individually."

Indeed, editing has become an ever more important tool in filmmaking. The use of jump cuts (edits that disrupt the continuity of a sequence) and quick cuts (rapid edits that increase the pace of a sequence) have become ever more common and familiar as action films and television have increased creators' reliance on editing as a central cinematic aesthetic.

But generally, video games don't have cinematic editing. They can't, because continuity of action is essential to interactive media. In fact, that continuity is so important that most games (3D games, anyway) give the player direct control over the camera, allowing total manipulation of what is seen and from what vantage point.

Perhaps, if we're being particularly generous toward cinema, we could count shifts in fixed-camera views in games like Heavy Rain and Metal Gear Solid as a type of jump cut, since the action is disrupted rather than continuous. But in most of these cases, shifts in camera correspond only with changes in location, not changes in the way a video game mediates the player's relationship to space or action or theme.

Survival horror games offer the best specimen of film-like editing in games. By holding the camera hostage, games like Resident Evil and Silent Hill remove player control, a technique needed to create tension and fear. The best example of this effect through camera editing alone might be Fatal Frame 2, which creates an effective sense of simultaneous familiarity and dread as the player moves through rooms of the possessed homes in a village.

In modern cinema, edits move action forward. Films are short compared to games, for one thing, but more importantly, editing helps a filmmaker focus the viewer's attention on important plot elements through abstraction. For example, instead of showing a character get ready and leave for work, a few rapid quick cuts can communicate the same information more efficiently: closet door opens, fingers button shirt, hand grabs keys, car backs out of driveway.

Like many interactive narratives, Heavy Rain appears to adopt the practice filmic editing by allowing the player to control how sequences of narrative appear based on quick-time event (QTE) actions. In this respect, it follows in a long lineage of titles starting with Dragon's Lair.

But that similarity is a foil. Instead, the most important feature of Heavy Rain, the design choice that makes it more important than any other game in separating from rather than drawing games toward film, is its rejection of editing in favor of prolonging.

Consider the game's first scene. The player not only must dress Ethan Mars piece by piece, but first he must get out of bed and take a shower. Stairs must be mounted and descended, one by one, with a deliberateness second only to that of Shenmue. Things only get more detailed from there: the player must help Ethan, an architect, do work by drawing portions of a building sketch in his home office. He must set the table. He must make coffee and move groceries.

Now, one might argue that the slow pace of the game's prologue is meant to teach the player how to control the character and execute QTEs. But later in the game, the unedited nature of these actions becomes completely central to a scene's meaning.

Consider the game's second chapter, in which Ethan loses track of his son Jason in a crowded mall, a mistake that proves dire. After buying Jason a red balloon, the boy wanders off and the player (as Ethan) must find him.

In this, the first of several excellent crowd sequences in the game, the confusion and crush of people gives the player a real sense of panic as Ethan moves from upper to lower level in the mall, then across its packed floor and out the front door, following both incorrect and correct clues in the form of floating red balloons.

Narratively speaking, the scene is abysmal. It is forced and obvious and unbelievable, and questions abound.

What ten year old begs for a balloon? How can such a slow-moving car fatally injure a child? Is Jason really so stupid as not to know how to cross the street? Why does Jason feel so compelled to leave his father in the first place?

But we don't really need narrative success to appreciate how truly frenzied the scene feels. In a film, that frenzy would be best carried out through a series of quick cuts: Ethan looking in different directions; a fast pan of the crowd, left and right; Ethan's movement through the mall concourse; a handheld first-person view down the escalators; more visually confused panning; a glimpse of a balloon; and then a cut to a different boy grasping it.

But as anyone knows who has actually lost a child in a public place, even if only briefly, the central sensations of that experience are not rapidness but slowness. The slow panic of confusion and disorientation, the feeling of extended uncertainty as moments give way to minutes -- the sound of each footfall and the neurosis of each head turn.

While its narrative fails to set up a credible reason for the chase, the chase itself captures this panic far more than a sequence of cinematic edits might do. If the edit is cinema's core feature, then Heavy Rain does the opposite: it lengthens rather than abridges.

But the mall scene is but a warm-up for one of the game's most successful experiments in retention: Chapter 3, Father and Son. It takes place two years after the previous chapter, and it's clear that Jason's death has all but undone Ethan. In his shoes, the player must pick up and drive Ethan's surviving son Shaun home from school. Home is revealed to be a run-down shack, its box-strewn living room implying that the aftermath of Jason's death has also involved the destruction of Ethan's marriage.

The game would clearly like the player to believe that this chapter will allow the player to alter the game's narrative based on decisions made on behalf of Ethan. A schedule is posted on the wall, detailing when Ethan should study, eat, and go to bed. If the player follows these, the "Good Father" PSN trophy is awarded, offering some undeniable textual evidence to place player choice at the apparent center of the sequence.

But once again, far more powerful ideas emerge from the scene's lack of cinematic editing rather than its abundance of cinematic plot.

In one sequence, the player makes dinner for Shaun. Ethan sits as Shaun eats, his pallid face staring at nothing. Time seems to pass, but the player must end the task by pressing up on the controller to raise Ethan from his chair. The silent time between sitting and standing offers one of the only emotionally powerful moments in the entire game.

Ethan says nothing. What is he thinking about? Is he mulling over what he might have done differently two years earlier? Is he fantasizing about his estranged wife? Is he lamenting the detachment he had exhibited moments ago toward Shaun? Is he plotting his return to professional success?

The game gives us no answers, but it invites the player to consider all these and many more by refusing to edit the scene down into a few moments of silence save the pregnant sounds of plate scraping and chair dragging. The mental effort the player exerts in this scene alone is orders of magnitude more meaningful than all the L1s and R2s Xs and Os in the rest of the game.

Another, equally intense sequence follows soon after. Upon being tucked into bed, Shaun realizes that his favorite teddy bear is missing, and reminds his father than he can't sleep without it. Once more, the game extends rather than compresses the hunt for the plush toy, as Ethan pads gloomily through the dark house in search of it.

Once the teddy bear is retrieved from atop the washing machine, another extended moment of reflection is possible, as the player is invited to consider the origin of the toy, and what secret meaning it bears for Shaun, Ethan, and perhaps even Jason. Was it a gift received during better times? An old toy of Jason's that Shaun uses as a tiny memory palace? By refusing to cut the scene short, the game effectively floods the player with possible implementations of this plush symbol.

In cinema theory, editing is sometimes contrasted with mise-en-scène, the establishment of a scene through sets, props, blocking, and other non-dialogic means. Mise-en-scène can communicate emotional intangibles through the repleteness of a setting.

For example, a shot of a refrigerator emptied of all contents save beer and pickles or of a large room of a loft with a cold concrete floor both might convey a sense of loneliness or isolation.

It's clear that Heavy Rain uses mise-en-scène extensively: the visual situation of the mall (crowded) and the house (in disarray) help orient the player toward the important actions of each respective chapter.

But cinematic mise-en-scène still must be communicated through editing. In film, it usually offers abstract, often contrived characterization through single shots or a concrete, if backgrounded, focus on space through long takes.

But it is not mise-en-scène that makes the chapter Father and Son emotionally evocative. Rather, it is the necessary absence of any such attention-directing devices thanks to a lack of editing in the interactive game world.

Cinematic shots of or through a scene are replaced by the weird, arbitrary movements that characterize 3D videogames. In the context of Counter-Strike or Gears of War, this movement becomes one of orientation toward objectives. But in a dramatic title like Heavy Rain, editing's absence invites players to discover, reveal, or create a few lingering, pregnant moments. These moments carry the game's dominant payload.

A final moment of prolonging punctuates the chapter, cementing the technique's potential as a first-order principle of game design. After tucking Shaun into bed, Ethan leaves, deploying the slow-rotated thumbstick QTE to close the door softly. In a film, this is where a good editor would cut to the next scene, allowing the door's latch to signal a fade to black and then a transition to the next chapter, Scott Shelby's encounter with Lauren White.

But in Heavy Rain, another option prevails. Faced with the bittersweetness of the situation, the player might turn back toward the door and simply look upon it, allowing the mixture of hope and despair inside of Ethan to dance with one another uncomfortably.

Heavy Rain's creators and critics have discussed its accomplishments in bringing video games closer to cinema, primarily by adding low-level interactivity and mild branching decisions to the thematic and narrative structure of traditional filmmaking. Such ideas have been around for 25 years, at least, from laserdisc coin-op to CDi and beyond, and they have enjoyed peaks and valleys of critical and commercial success during that time.

But perhaps there is something far more interesting at work in Heavy Rain: its successful rejection of the primary operation of cinema. The game doesn't fully succeed in exploiting this power, but it does demonstrate it in a far more synthetic way than do other games with similar goals. If "edit" is the verb that makes cinema what it is, then perhaps videogames ought to focus on the opposite: extension, addition, prolonging. Heavy Rain does not embrace filmmaking, but rebuffs it by inviting the player to do what Hollywood cinema can never offer: to linger on the mundane instead of cutting to the consequential.

It's something to let Ethan ponder as he leans against the railing of his motel balcony, watching the rain fall endlessly.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like