Persuasive Games: The Birth and Death of the Election Game

Author and game designer Bogost examines the use of video games in 2004 and 2008's U.S. Presidential election, seeing a sharp decline in games used for political means this year, and simply asking - why?

[Author and game designer Bogost examines the role of video games in 2004 and 2008's U.S. Presidential election, seeing a sharp decline in games used for political means this year, and asking a simple question -- why?]

The 2004 election cycle saw the birth and quick rise of the official political video game. While election strategy game have been around since 1981's President Elect, that title and its followers were games about the political process, not games used as a part of that process.

2004 marked a turning point. It was the year candidates and campaign organizations got into games, using the medium for publicity, fundraising, platform communication, and more.

That year, I worked on games commissioned by candidates for president, for state legislature, by a political party, and for a Hill committee. And that was just me -- other endorsed political games abounded, from the Republican Party to the campaign for President of Uruguay.

It was easy to get public attention around such work, and indeed one of the benefits of campaign games revolved around their press-worthiness. By the final weeks of the last election cycle, all signals suggested that campaign games were here to stay.

Drunk on such video game election elation, I remember making a prediction in a press interview that year: in 2008, I foolishly divined, every major candidate would have their own PlayStation 3 game.

MSNBC writer Tom Loftus made a similar, albeit wisely milder prediction in late October 2004: "Already tired of hearing politicians say 'visit my Web site' every five minutes? Wait until 2008, when that stump speech staple may be replaced with a new candidates' call: 'Play my game.'"

We couldn't have been more wrong.

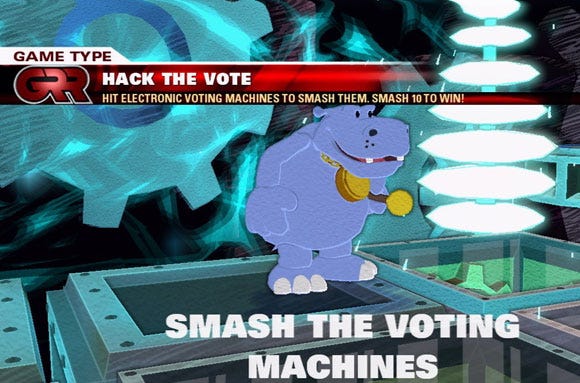

Looking back on the 2008 election, video games played a minor role. In terms of officially created or endorsed work, only a few examples appeared. The McCain campaign served up Pork Invaders, a Space Invaders clone in which a McCain "ship" fires vetoes at pig "aliens" as a demonstration of how McCain "would exercise the veto pen to restore fiscal responsibility to our federal government."

The game boasts higher production value than the GOP's similar 2004 offering, Tax Invaders, but is considerably less sophisticated as political speech.

The game boasts higher production value than the GOP's similar 2004 offering, Tax Invaders, but is considerably less sophisticated as political speech.

Tax Invaders cast taxes in the role of the alien enemy and George W. Bush as the executive-hero who would save the people from them, an apt characterization of conservative tax policy that actually benefits from having been cast in a video game.

By contrast, Pork Invaders struggles to connect gameplay to political message; it's mostly a curiosity.

The most visible video game politicking of 2008 came recently, in the form of the Obama campaign's decision to buy dynamic in-game ads in console games like Burnout Paradise. Gamers welcomed the buy; it appeared to suggest that Obama at least did not intend to vilify their medium, despite having previously encouraged parents to "turn off the television set, and put the video games away."

Given Obama's enormous war chest, the move must have looked like a risk-free experiment to the campaign. Still, the Democrats didn't make any games of their own, a feat met (even if barely) by McCain's hammy offering.

Unofficial political games also made few innovations this year. The largest crop of them are game-like gags about Sarah Palin, from the almost-topical Polar Palin to the toy-like Palin as President to the wildlife sendup Hunting with Palin to a series of Palin chatterbots to the inevitable whack-a-mole clone Puck Palin.

The few non-Palin titles included a retooling of 2004's derivative White House Joust; Truth Invaders, another Space Invaders derivative in which the player shoots down lies; Debate Night, a Zuma-style casual game in support of Obama, and Campaign Rush, a click-management election office game my studio developed for CNN International.

Of these, only Truth Invaders cites actual candidate claims and attempts to refute them, although in a fairly rudimentary way; the others do not engage policy issues at all, but only electioneering.

Three decades after its coin-op release, it's disillusioning to realize that Space Invaders has become the gold standard for political game design.

The turnout for commercial games with political themes also thinned this cycle.

In 2004, no less than four different election simulation games were released; this year, Stardock retooled and updated Political Machine for PC and released a free web version of the game.

Beyond that, the strongest example of a mainstream game coupled to the election season is the "political brawler" Hail to the Chimp.

Stardock's The Political Machine 2008

There are reasons games have grown slowly compared to other technologies for political outreach. The most important one is also the most obvious: since 2004, online video and social networks have become the big thing, as blogs were four years ago.

Instead of urging voters to "play my game," as Loftus and I surmised, candidates urged their constituents to "watch my video."

Online video became the political totem of 2008, from James Kotecki's dorm room interviews to CNN's YouTube debates. At the same time, the massive growth in social network subscriptions made social connectivity a secondary focus for campaign innovation, especially since Facebook opened its pages beyond the campus in 2006.

In many cases, politicking on social networks was a process driven entirely by voters rather than campaigns, efforts that reached far larger numbers than might have been possible previously, even with blogs.

For once, video games did not lose an election by sticking their collective necks out as a sacrifice for values politics, the kind that Senators Hillary Clinton and Joe Lieberman, among others, have used to shift their base toward the center.

For better or worse, the world is too legitimately messed up for such politics to prove useful. Instead, video games lost the election by not participating in it. Precedent aside, reskinning classic arcade games and placing billboards in virtual racetracks doesn't take advantage of the potential games have to offer to political speech.

To understand why, we need to comprehend the difference between politics and politicking. Politicking refers to campaigning, it's the process we see and hear about throughout the election cycle: the yard signs, the television ads, the soapboxing, even the debates. Politicking is meant to get smiling faces and simple ideas in front of voters to appeal to what ails them.

Politics, if we take the word seriously, refers to the actual executive and legislative effort that our elected officials partake in to alter and update the rules of our society. In an ideal representative democracy, the one leads to the other, but in contemporary society the two are orthogonal.

Ironically, this is exactly where video games would find their most natural connection to political speech.

When we make video games, we construct simulated worlds in which different rules apply.

To play games involves taking on roles in those worlds, making decisions within the constraints they impose, and then forming judgments about living in them.

Video games can synthesize the raw materials of civic life and help us pose the fundamental political question, What should be the rules by which we live?

Such questions are rarely posed nor answered seriously in elections. Indeed, the electoral process has become divorced from the process of establishing and enforcing public policy.

The solution to our medium's failure to engage elections in 2008 is not to wait and try again in 2010 or 2012; indeed, the best solution may be to abandon the "election game" entirely, in favor of the public policy game.

What if you could live a mirror life in the evolving world of your US senator or city councilor's policy promotions: How would a community benefit from a bond measure in relation to its actual cost to taxpayers?

What would it feel like to live under the constraints of a particular fiscal policy? How might an unorthodox energy policy balance environmental and security concerns? Why will federal investment in private banking positively impact business and ordinary citizens?

In other words, the benefit video games can offer public life is to deemphasize politicking in favor of politics. As the 2008 election fades into memory, it is here that we should steer our medium's engagement with politics, whether through official publication by the elected or independent creation by the electorate.

The role of video games in politics lies here, in their potential to unseat elections as the unit of popular political currency, rather than to participate in them directly.

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)