Persuasive Games: Texture

Author/designer Ian Bogost (Fatworld) looks at 'texture' in games - the art of connecting the virtual to the real via rumble and physical simulation, from Hard Drivin' to Rez and beyond.

[As part of his regular Gamasutra column, author/designer Ian Bogost (Fatworld) looks at 'texture' in games - connecting the virtual to the real via rumble and physical simulation, from Hard Drivin' to Rez.]

I enjoy the ancient Chinese strategy game Go, although I am hardly an expert. The open-source GnuGO AI built into the computer version of the game I play overpowers me much of the time.

After many years of having gone without, I recently received a Go board and set of stones as a gift. Immediately I noticed the most important difference between playing on the computer and off it: touching the board and the stones.

I had forgotten what a tactile game Go is. The black and white often have a different texture from one another, depending on the type and quality of stones one uses.

The feel and weight of them between the fingers somehow aids the pondering that comes with their placement.

Once the player chooses a move, placing the stone on a real board offers a far more tactile challenge than clicking an on-screen goban. The stones move, so disrupting the board is an easy feat that must be carefully avoided. Traditionally, Go players would hold a stone between the index and middle finger and strike their move, so as to create a sharp click against the wooden board.

Go is a cerebral, minimalist game that exudes purity and austerity. Computer versions of Go adapt these values unflappably. Although purists favor silence in selecting and holding a stone, for me Go is a game of rummaging for a stone in a smooth wooden bowl and stroking it in thought before placing it to mark territory.

These features are not unique to Go, but they are distinctive. In Chess, the pieces rest on the board, or off, never to be touched save to punctuate decision. Although both games are cerebral, Go is far more sensual.

Go reminds us that the physical world -- games included -- have texture. They offer tactile sensations that people find interesting on their own.

Texture in Media

In painting, texture is a more frequently recognized aspect of creativity. The word describes the weave of the canvas, the application of the medium upon it, and the interaction of the two. It is a feature that frequently earns mention among critics and casual observers alike as a fundamental part of the finished work.

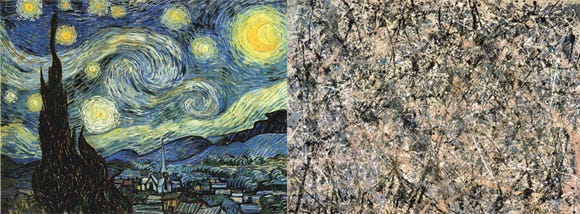

Impressionist painters like Vincent Van Gogh used thick applications of paint, partly to recreate the effects of light on the surface of the canvas itself as well as in the subjects represented.

And Jackson Pollock's abstract expressionist work relies almost entirely on texture; Pollock even added grains of sand and shards of glass to his already viscous industrial paints to increase the texture of the finished work.

Van Gogh's Starry Night, Pollock's Number 1, 1950 (Lavender Mist)

Other media adopt their own understandings of texture. In the culinary arts, texture refers to the physical sensation of a food in one's mouth, such as the crispness of a cucumber or the slipperiness of an oyster.

And in music, texture is used metaphorically to refer to the relationship between sounds and voices in a piece -- as if they were layered through time like paint on a canvas.

Texture in Video Games

In the era of 3D computer graphics, texture is a term frequently used in technical talk about video games. Textures are the graphical skins laid atop 3D models so they appear to have surface detail.

Texturing techniques like bump mapping and normal mapping use two-dimensional image data to perturb the lighting patterns applied to objects by 3D rendering algorithms to make them appear to have a surface texture that is not actually present in the 3D model itself.

These simulate the appearance, but not the behavior or sensation of texture. This is nothing new; the fine arts have often done similar.

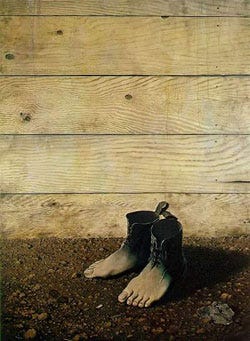

Surrealist Réne Magritte was particularly adept at creating the appearance of texture in his subjects with color and tone rather than paint thickness.

In Magritte's "Le modèle rouge," the texture of the wood slats and the dirt ground jump out as familiar textures, despite the flatness of the artist's brush technique.

Epic Games' Gears of War -- it's all about the texture(s)

But unlike paintings and plats principaux, games are not static scenes or objects -- they are interactive models of experiences. To simulate the behavior, rather than just the appearance of texture, games have to use more than visual effects.

But unlike paintings and plats principaux, games are not static scenes or objects -- they are interactive models of experiences. To simulate the behavior, rather than just the appearance of texture, games have to use more than visual effects.

Sound design is one answer: footfalls or bullet casings can produce different noises when falling on grass, dirt, concrete, wood.

A character wading through tall grasses causes the blades to swoosh around him. When steered off the road, a car's tires grind against gravel.

Simulated properties of the physical world can also contribute to texture. A game might slow a character's movement through brush or swamp, as do both realistic first-person shooters like Far Cry and abstract strategy games like Advance Wars.

Likewise, driving games from Pole Position to Burnout alter a vehicle's speed and handling when it moves across different surfaces, simulating the differences in traction. Friction is another frequently simulated texture: platformer games like Ice Climber simulate the reduced friction of ice-covered surfaces.

In all these cases, video games simulate the texture of the real world in two ways: through visual appearance or effects.

A stone cavern wall or a splintered wood floor communicates texture by appearance. Contemporary graphics processing units make the surface textures of objects in games appear lifelike, just like the wood slats in Magritte's painting.

When the player moves around in these worlds, the renderer's real-time updates reinforce the sense of texture in the scene by offering different views of the same surfaces.

The driver's shoulder or the soldier's swamp communicates texture by effect. When the player operates machines or moves creatures, their behaviors are constrained by the physical consequences certain textures represent.

Force Feedback

In such cases, the player still does not feel the texture of the road or the brush of the grasses when he plays, but only the cold plastic of the controller. Unlike painting and sculpture (which forbid touch) and music (which cannot accommodate it), video games require user participation.

Even though image and sound comprise much of their raw output, touch is an undeniable factor of gameplay.

Force feedback, motion simulation, and vibration have been built into expensive flight and military training simulators for decades.

By the 1980s, some of this technology made its way into the arcade. 1988's driving sim Hard Drivin' featured force feedback steering, which resisted player rotation at higher speeds and rumbled on collision.

Tactile computer interfaces, or haptics, became a consumer industry by the early 1990s, with companies like Immersion developing cheaper, simpler sensors and motors that allowed such devices to be integrated into objects other than the expensive, awkward gloves and vests of dedicated virtual reality labs.

Thanks to the Nintendo 64 Rumble Pak add-on, we usually call haptic feedback in video games "rumble." Rumble allows games to create tactile sensations in addition to visual and aural ones. Cars can now seem to bump with the changing texture of asphalt, gravel, dirt.

Technically, rumble in contemporary game systems is more or less all alike: motors spin one or more unevenly molded weights in a housing within the body of a controller.

But despite the simplicity of rumble, its effects are quite varied: the pulse of a heartbeat signifies health and instills fear in Silent Hill; a tackle in Madden NFL registers physically as well as visually; the tremor of a gunshot in Call of Duty alerts the player to unseen dangers from behind or above; the vibration of the steering wheel in Gran Turismo communicates the force of cornering around a hairpin at speed.

The subtle signal of a motor signals the cursor entering a button in the Wii Sports menu screen; a jolt to the hand in MVP Baseball alerts the player to an opponent stealing base; a spin of the the rumble pak in The Legend of Zelda: The Ocarina of Time signifies the loose feel beneath Link's feet when a treasure is buried beneath the ground he stands upon.

In general, the use of rumble is of two kinds: the first (as the name of the company that licenses the technology suggests) is increased immersion. Rumble is supposed to make the player feel more a part of the game in titles like Madden or Silent Hill. The second is better feedback. In Wii Sports and Ocarina of Time, rumble helps the player orient himself toward certain interface or gameplay goals.

Despite the utility of rumble in these cases, there is something missing. Rumble infrequently communicates texture in the way that paint, food, or even 3D bump mapping does: the texture always has purpose, never just aesthetics.

Put differently, rumble is an instrumental kind of texturing: it makes the environment tactile only to allow the user to make better progress within it. Even 3D rendered texture is not so brazen about its focus on function: one can comfortably look in simple admiration at the walls and floorboards of a room in Half-Life 2.

From Feedback to Sensation

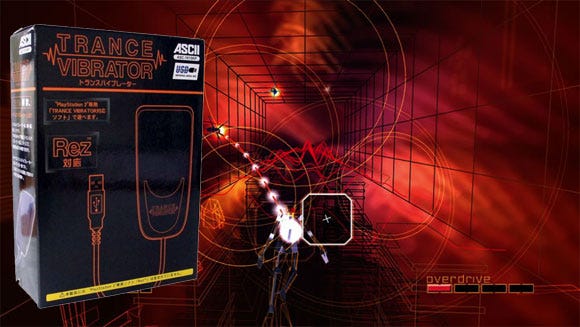

There is at least one example of a game that uses rumble to provide direct, tactile sensation instead of feedback. And surprisingly, this title relies on a musical rather than physical texture as its primary tactile inspiration.

Tetsuya Mizuguchi's Rez is a psychadelic, abstract rail shooter first released for Sega Dreamcast in 2001.

The game is set in the data flow of a computer network, where the player takes on the role of a hacker trying to reboot the system while destroying enemies like viruses.

Mizuguchi cited synesthaesia, the unity of the senses, as an inspiration for the game. It combines striking visual, musical, and manipulative experiences all at once.

As a part of this goal, the Japanese special edition of the PlayStation 2 version of the game included a "trance vibrator," a large plastic dongle that plugs into the console via USB. The device has no inputs, but houses a rumble motor within.

When Rez is played with the trance vibrator active, the device pulses in time with the trance eletronica music that plays during the game. The music, in turn, signals the position of enemies in time with the beat.

The player already has a tactile relationship with the music via timed button presses on the controller, but the trance vibrator allows him to experience the texture of the music, translated into continuous tactile sensations, at the same time as the musical texture is also translated visually into neon abstractions.

Although Mizuguchi denies that the trance vibrator was intended to be a sexual add-on for Rez, that obvious use has been well documented. The potential for sexual pleasure only underscores the way Rez's use of rumble focuses on a different kind of tactility than does Halo or Gran Turismo: in Rez, the player touches the surface of the game itself. The texture of neon light and synth phrases produce a surface one can literally feel.

Video Games that Touch

The abstraction and immoderation of sensation in Rez offers an extreme example of videogame texture, one few games could or should replicate. But Rez sends a signal that other games might wish to tune in.

Just as the texture of a tufted wool rug can please the toes, or the texture of a piece of unagi atop nigiri sushi can please the tongue, so similar tactility can please the body of the gamer. These are pleasures far more subtle and confounding than the anonymous fun of solving a problem in a game.

It might be possible to simulate the tactile pleasures of Go in a videogame. Removing the snap-to-grid stone placement would be a start. A physics simulation could allow perturbation of the stones when they touch, just as so many games do with crates and with barrels. A videogame adaptation could depict the bowls of stones and use a fluid dynamics model to allow the player to stir it while he considered a move, or to spin it in a virtual hand.

Such simulation might successfully refer to the tactility of the original, but that appreciation would quickly become conceptual, lost in the limitations of mouse or analog stick compared to fingers.

Still, the potential is great. We craft every aspect of videogame worlds in excruciating detail: the marbled, diffracted surfaces of water, the filthy grit of alleyways, the splintered grain of bombed-out church rafters.

We render the visual and aural aspects of these worlds in startling vividness and at great expense. But those worlds remain imprisoned behind the glass of our televisions and our monitors. Rez shows us that as far as texture is concerned, games can be as much like food as they are like film.

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)