Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Good puzzle games are often described as addictive, elegant or deep, but in reality they can elicit deeper feelings of overwhelm, vastness and abundance, says designer Ian Bogost.

[Good puzzle games are often described as addictive, elegant or deep, but in reality they can elicit deeper feelings of overwhelm, vastness and abundance, says author and game designer Ian Bogost in his latest Gamasutra column.]

I want to discuss two excellent abstract puzzle games for the iPhone: Drop7 by Area/Code and Orbital by Bitforge. But there's a problem: it's hard to talk about abstract puzzle games, particularly about why certain examples deserve to be called excellent.

Sure, we can discuss their formal properties, or their sensory aesthetics, or their interfaces. We can talk about them in terms of novelty or innovation, and we can talk about them in terms of how compelling they feel to play. But such matters seem only to scratch the surface of works like Drop7 and Orbital.

Can we talk about such games the way we talk about, say, BioShock or Pac-Man or SimCity? All of those games offer aboutness of some kind, whether through narrative, characterization, or simulation. In each, there are concrete topics that find representation in the rules and environments.

Indeed, it's hard to talk about abstract games precisely because they are not concrete. Those with more identifiably tangible themes offer some entry point for thematic interpretation.

Chess, for example, clearly draws inspiration from military conflict, not only because of its historical lineage and mechanics of capture, but also thanks to its named, carved pieces. When a knight takes a pawn, it's easy to relate the gesture to combat.

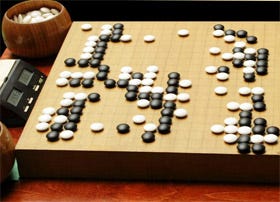

Go is somewhat harder to characterize. As philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari wrote of the game, "Go pieces, in contrast [to chess], are pellets, disks, simple arithmetic units, and have only an anonymous, collective, or third-person function: 'It' makes a move. 'It' could be a man, a woman, a louse, an elephant."

Even if one can imagine a go stone as a soldier or an elephant or a Walmart, the game is still fundamentally about territory: whoever captures more of it wins.

Puzzles create more trouble. Some logical and mathematical puzzles, like the Three Utilities Puzzle have clear subjects or storylines. Others, like sudoku, do not. Most often, puzzles are entirely conceptual in form, with concreteness a mere accident of presentation.

Puzzles create more trouble. Some logical and mathematical puzzles, like the Three Utilities Puzzle have clear subjects or storylines. Others, like sudoku, do not. Most often, puzzles are entirely conceptual in form, with concreteness a mere accident of presentation.

A jigsaw puzzle might have a landscape or a hamburger imprinted on its completed surface, but that subject bears no relation to the puzzle itself. It's just a skin that facilitates the job of construction. The same is true of some manipulable puzzles, like tangrams.

Others, like peg solitaire and Rubik's Cube are entirely abstract, with no clear relation to any sort of worldly being or action.

As we know well, video games have frequently inherited from the tradition of puzzles. Text and graphical adventures make use of logical puzzles, often ones that require manipulating items to unlock doors. And we have plenty of adaptations of traditional abstract board games. But it's really manipulable puzzles that have had the strongest influence on contemporary abstract games, and for good reason: spatial relations translate well. Video games are good at manipulating objects in space.

A problem arises when we try to talk about abstract puzzle games critically. The truth is, it's hard to perform thoughtful criticism on puzzles, because they don't carry meaning in the way novels or films or oil paintings do. The peg solitaire set on the table at Cracker Barrel does not function as a religious text, for example.

One approach to understanding abstract art is to treat them as metaphors or allegories. In some cases, the art helps us out by means of its title. Marcel Duchamp's cubist painting "Nude Descending a Staircase" immediately reveals the multi-perspective, superimposed forms of a human form in motion. The same goes for Piet Mondrian's famous final painting, "Broadway Boogie Woogie," which reflects the bustle of New York City.

In other cases, no such help can be gleaned from the work itself, and viewers must seek their own interpretations. Such is the case with Mondrian's "Composition with Yellow Patch," for example, which offers no interpretive handle in its title or on its canvas.

Games rarely give much away through their titles, mostly because they don't have a strong genealogical relationship with the history of painting. Still, our interpretive capacity makes it possible to read meaning in anything if we choose.

Perhaps the best-known representational interpretation of an abstract puzzle game addresses the best-known such game: Tetris. In her 1997 book Hamlet on the Holodeck, Janet Murray described Tetris as "the perfect enactment of the overtasked lives of Americans." Tetriminoes fall, like tasks to be completed, emails to be read, meetings to be attended. One must act quickly or the onslaught will quickly overwhelm. But once checked, filed, or satisfied, the process just starts all over again. There is no escape, save inevitable defeat.

Critic Markku Eskelinen pugnaciously disputes Murray's account as absurd: "Instead of studying the actual game Murray tries to interpret its supposed content, or better yet, project her favourite content on it; consequently we don't learn anything of the features that make Tetris a game."

Eskelinen points out the curiosity in reading a Soviet game as an allegory for the American work ethic, and offers that "It would be equally far beside the point if someone interpreted chess as a perfect American game because there's a constant struggle between hierarchically organized white and black communities, genders are not equal, and there's no health care for the stricken pieces."

Yet, Murray's interpretation is entirely reasonable. From the perspective of literary or art criticism, she offers something essential: evidence from the work itself. The fact that the game was made behind the Iron Curtain doesn't matter; a work escapes the context of its creation and recombines with new interpretations in myriad unexpected ways (a concept the philosopher Jacques Derrida calls dissemination). Nobody can tell you what a work "really means," provided you can mount textual evidence to show that your interpretation is sensical.

The problem with the Murray/Eskelinen approach to abstract puzzle games is that one wants the game to function only narratively, the other wants it to function only formally. Neither is exactly right without the other. The problem seems to be this: the "meaning" of an abstract puzzle game lies in a gap between its mechanics and its dynamics, rather than in one or the other.

In his eighteenth century tome on aesthetics, the philosopher Immanuel Kant distinguishes between the beautiful and the sublime. He relates beauty to non-logical, subjective aesthetic judgments about the form of things. He describes the sublime in terms of a relationship between the faculties of imagination and reason.

Kant characterizes two kinds of sublimity. The mathematical sublime is a feeling of boundlessness or vastness, as caused by reflections on the infinitely large. A pyramid is an example of such a structure, one that cannot be wholly taken in in a single gaze.

The dynamical sublime describes the feeling of being overpowered. This latter sense often comes from natural objects such as the face of a cliff over the sea, or of an enormous thunderhead. Sensations of the mathematical sublime arise from largeness; sensations of the dynamical sublime arise from fear.

I submit that the meaning of games like Drop7 and Orbital are best understood in relation to the sublime, and particularly to the mathematical sublime.

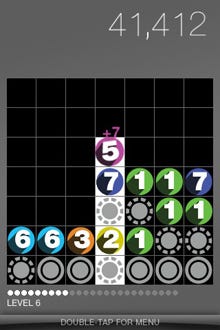

Drop7 asks the player to drop discs emblazoned with a number from one to seven down the columns of a 7x7 grid. Gravity carries them until they reach bottom or stack atop other discs. If a disc's number matches the quantity of discs in a row or column (no matter their numbers), the matching disc disappears.

Grey discs cannot disappear, until they are unlocked to reveal a number. This is done by causing a numbered disc to disappear adjacent to the grey disc two times. Points are scored for each disappearing disc, with bonuses awarded for chains and board clears.

Much is left to chance in Drop7. The board starts with some discs already in place, and each disc the player must place is drawn randomly. In some cases, a convenient number appears, allowing the player to execute a planned chain or avoid a dangerous situation. In other cases, an undesirable disc forces the player to change plans. Furthermore, when grey discs appear, their contents remain unknown to the player until surrounding discs reveal them.

All together, these mechanics require the player to reassess the state of the board each turn. Grey discs can be taken as uncertainties, but doing so is unwise. It's much smarter to assume the worst of hidden numbers and plan accordingly.

Yet, even then, each turn requires a total reassessment of the state of the board based on the last turn's results and the present disc. While emergent consequences exist in chess and go, Drop7 makes the long-term impact of a single move visible even to the amateur player.

The experience of playing Drop7 is thus one of planning present moves against a series of contingent future ones, given a set of slowly changing uncertainties. The vastness of possible moves is calculable for a moment, until it is disrupted by the randomness of new information. This is where the player finds the game's mathematical sublimity.

The experience of playing Drop7 is thus one of planning present moves against a series of contingent future ones, given a set of slowly changing uncertainties. The vastness of possible moves is calculable for a moment, until it is disrupted by the randomness of new information. This is where the player finds the game's mathematical sublimity.

Mastery of the game is always temporary, as each move collapses the innumerable possibilities that exist before a disc drops into the fixity of a new situation just after. Yet, unlike the constantly changing dynamics of a chess or go board, each move in Drop7 reveals something more about itself later on, as previously unknowable impacts begin to exert torsion on the present.

In Orbital, the player fires orbs from a rotating gun at the bottom of the playfield. These orbs ricochet off walls and one another, until inertia stops them. Once stopped, the orbs grow until they touch a playfield wall or another ball.

The player's goal is to break the orbs by striking them three times with new ones (a large counter on each ball shows the current hit count), scoring a point. However, should an orb bounce such that it passes a white line just above the player's gun, the game is over. Following its cosmic theme, the orbs in play create gravitational fields that alter the path of subsequent ones.

Like Drop7, players of Orbital suffer under an environment dependent on the increasing contingency of aggregate moves. One tactic for play involves estimating the trajectories of orbs based on the friction and gravity of the environment. One can, for example, attempt to lodge a cluster of small orbs in the corners, increasing the likelihood of destroying many with a single shot.

Yet, as each orb settles, it alters the gravity well of a part of the playfield, effectively erasing whatever understanding the player had developed about the earlier topology. Notably, this same disorientation occurs even when the player succeeds, since an exploded orb alters local gravity too.

In Drop7, the mathematical sublime enters the game primarily through chance: the random generation of discs under the grey coverings and in the player's hand. In Orbital, there is no chance whatsoever. Every move in the game is calculable. Yet, the vastness of the ever-changing universe makes such planning impossible for the human player, who must win out over both timing and physics to carry out a shot intentionally, whether or not it was well-planned in the first place.

Orbital is less forgiving. While Drop7 slowly winnows down choice until the player is overcome by failure, Orbital puts failure on the screen, a thin, fragile line subject to even the lightest graze.

To play Drop7 or Orbital is to practice string theory, to assess the unknown branches of infinite futures. Whether one plays effectively or not, these games force players to reflect upon the mathematical boundlessness of the systems that drive them, systems that alter themselves with every move.

Can we say that Drop7 and Orbital are "about" something? And if so what? Here it is useful to return to Murray's interpretation of Tetris.

One might find a similar mathematical sublimity at work in Tetris, after all. Each block alters the topology of the playfield, the player must alter that topology to continue the game, and chance dictates what pieces might be available to consummate the geometrical promises made earlier.

But Drop7 and Orbital differ from Tetris in an important way: they are turn-based, not continuous. The player must always intervene to make the next move, offering an opportunity to reflect on the enormity of the task, a requirement of sublimity.

When Murray reads Tetris as a work about the Sisyphean toil of work, she refers not to the game's dynamics of mathematical sublimity, but to the temporal dynamics of its operation. And time, as it happens, is precisely the formal explanation Eskelinen's offers after his rebuff of Murray's narrativism.

Office work is generally not a variety of sublimity like the rapidly branching parallel worlds of Drop7 and Orbital, but it is often an experience of time's arrow, of unstoppable progression, with or without progress.

In Tetris, the method of play disrupts access to the sublime. But in Drop7 and Orbital, the player's pondering of and reaction to sublimity is enhanced by the mode of action. Arrested between each move, it is possible to allegorize that sensation, taking it as the subject of the game.

For example, Drop7 offers an experience of dread and smallness in the face of unpredictability -- not only of the future (the disc to be placed), but also of the past (the unrevealed grey discs). Such an experience feels much like that of, say, personal choice. Should one contribute to the Red Cross? Convert to Islam? Take a mistress?

To be sure, the surface and model of Drop7 do not feel like this at all, but the experience of mathematical sublimity are alike in both cases.

In this respect, one might argue that Drop7 is more about moral choice than are games like Fable or BioShock. The latter titles may simulate the actions of decision, but just like Tetris does for work, they do not capture the theme of choice through dynamics.

Orbital can be seen to build on this theme, but in a different direction. Absent chance, Orbital's subject revolves around placement. Even given the full knowledge of the physical dynamics of the universe (a subject that finds its way into the visual theme of the game), the human player is still too fallible to succeed at such placement over time. Even the master will be found wanting; after all, the current global high score for Orbital is under 200 points.

Orbital can be seen to build on this theme, but in a different direction. Absent chance, Orbital's subject revolves around placement. Even given the full knowledge of the physical dynamics of the universe (a subject that finds its way into the visual theme of the game), the human player is still too fallible to succeed at such placement over time. Even the master will be found wanting; after all, the current global high score for Orbital is under 200 points.

This interpretation of these games, one among many, cannot be gleaned from game mechanics, nor from the dynamics those mechanics produce. Instead, they take form in the allegorical exhaust of player sensations between the two.

Good puzzle games can do many things. But to call them good based on properties of addictiveness or depth or elegance -- the common values used to judge titles like Tetris and Drop7 and Orbital -- is to say that abstract games can only exert cold, formal effect on their players. The sublime is just the opposite of cold formalism: a feeling of overwhelm, of vastness, of abundance.

The sublime helps us see the limits of our own reason, showing us the instability and immensity of the world. Surely such a theme hasn't been exhausted by a few games about blocks and numbers and shapes, just as it hasn't been captured by a few games about war or sacrifice or loss.

The role of the mathematical sublime in puzzle games should give us pause about our goals as creators and critics. We look for masterpieces in games by comparing them to familiar works of representational art, like film, painting, and literature. But the sublime is found elsewhere: in architecture, in nature, in weather. Perhaps we should look to these sources for inspiration too.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like