Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Ian Bogost explores how an unprecedented event at Wimbledon can illustrate the boundaries of a system never before reached -- and how the console cycle doesn't allow for this sort of exploration in the art of game design.

[In his latest Gamasutra column, writer and game designer Ian Bogost explores how an unprecedented event at Wimbledon can illustrate the boundaries of a system never before reached -- and how the console cycle doesn't allow for this sort of exploration in the art of game design.]

Consider two sorts of familiarity that arise in art.

The first is the familiarity of predictability. Through craft, this sort of work gives us what we expect in a well-conceived fashion. It's one of the reasons people enjoy television. The sitcom and the procedural tend to be particularly good at giving us what we expect. In twenty minutes, a banal family crisis can flare up and be resolved. In forty, a duo of detectives can track down and book a murderer. Primetime television is a place we can go to be reassured, to avoid surprises.

The second kind of familiarity is that of deep exploration. Less formulaic works embrace uncertainty, taking us through themes or to places we thought we knew well, but which we later realized we hadn't considered fully.

Novels, feature films, even the intricate story lines of more adventurous television series like The Wire or Lost hope to jostle our minds out of their comfort zone. When done well, this sort of art startles us out of mechanical slumber and shakes us to our core with the astounding novelty of unseen, yet now obvious truths.

We might call the first kind of familiarity the "familiar unfamiliar." It gives us something we already know in a slightly different form. The second, by contrast, we could call the "unfamiliar familiar," because it shows us something we didn't even think to consider about a domain we thought we knew through-and-through.

Video games think they embrace the latter sort of familiarity, but in fact they almost always typify the former. To see why, let's take a look at two events that took place last month, both of which enjoyed so much publicity that you'll already be intimately familiar with them, although perhaps not in the way you think.

As they do every year, thousands gathered in Los Angeles for E3, the video game industry's main trade event. It's a time when hardware manufacturers, publishers, and developers showcase their latest wares for retail buyers and, more broadly, for the industry and enthusiast press. This year's expo offered no small measure of excitement thanks to new announcements about highly-anticipated products and systems.

Among them was Microsoft's motion control system Kinect, the first revelation of the project formerly known by its code name Natal. Sony followed suit, showing off PlayStation Move, its wand-like physical controller.

Among them was Microsoft's motion control system Kinect, the first revelation of the project formerly known by its code name Natal. Sony followed suit, showing off PlayStation Move, its wand-like physical controller.

Trends in 3D took shape too. Sony announced aggressive support for 3D gaming, but Nintendo stole the show with its impressive 3DS handheld, which offers 3D imagery without the use of special glasses.

For much of its history, the video game industry has counted on five- to ten-year hardware advances like these to drive and refresh player interest. In part that's because microcomputers have come a long way in the forty years since games on computers have been a viable market, growing from literally nothing to the portable supercomputers we enjoy today.

But hardware innovation also underscores an often cited but infrequently analyzed assumption among the industry: new gadgets are supposed to "revolutionize" the way we play. Nintendo made such claims when it designed the Wii (codename "Revolution"), as did Microsoft with the original Xbox, and Sega with the Dreamcast, and on back as far as one cares to recall.

Whether it's a motion controller or a multicore GPU or a 3D display, the industry assumes that new technology embraces unfamiliar familiarity. Kinect, like the Wii before it, is supposed to show us how easy and intuitive play can be, and how mistaken we were ever to think otherwise. Sony and Nintendo's 3D displays are meant to immerse us in experiences that will leave us wondering how we ever tolerated the flat plainness of two dimensions -- just as 3D games of the N64/PlayStation era did fifteen years ago.

The problem is this: while the experiences promised by technical shifts always produce excitement, that excitement is usually short-lived and rarely deeply meaningful. New tech succeeds in buoying the business of games for another few years, but only until players realize that the unfamiliar wild west of technology really amounts to yet another take on the familiar ordinariness of incessant gadgeteering.

One need look no further than the games themselves to see just how familiar are video games' cyclical promise of unfamiliarity. Kinect Sports offers simple takes on athletics. Kinect Joy Ride is a kart racing game. Kinectimals revisits the virtual pet. Ubisoft's Your Shape: Fitness Evolve revisit's Wii Fit and EA Sports Active for Kinect. Dance Central follows in the footsteps of Dance Dance Revolution and its kindred. Over in Nintendo's corner, new versions of Zelda, Mario, GoldenEye, Kirby, Metroid, Dragon Quest, Donkey Kong, and Kid Icarus make their way onto hardware old and new.

It's understandable that we would appreciate these games. Like The Cosby Show or Law & Order, they give us exactly what we expect. Mario still jumps and saves the princess, Link still swings his sword and saves the princess, Donkey and Diddy Kong still ground pound and race mine carts, Samus is still a girl, kart racing is still wacky, and jumping around the living room swatting at shadows is still fun.

But just as sitcoms and police procedurals offer only skin-deep explorations of human experience, so generation after generation of video games offer skin-deep explorations of the very subjects we believe them to be getting so much better at simulating.

On the one hand, there's nothing wrong with this. Just as there's a place for another episode of Everybody Loves Raymond or CSI, so there's a place for another take on fantasy swashbuckling or platforming. But on the other hand, mistaking those examples of the familiar unfamiliar for truly deep and novel explorations of even the very themes they offer reveals a missed opportunity.

A week after E3 and halfway around the world from Los Angeles, John Isner battled Nicolas Mahut in what became the world's longest tennis match. For three days Isner and Mahut hit fuzzy rubber balls across the grass courts of Wimbledon. It was a first round match, one of sixty-four in the men's tournament, tucked away in one of the many side courts of the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club.

As befits the oldest tennis tournament in the world, there was nothing new about Isner and Mahut's match. The grass of the All England Club's courts grows the same as it ever has. The materials of shoes and fabrics and racquets and balls have surely improved over the years, but the game still requires only the very basics that Kinect and Move claim to rediscover boldly: men with sticks run to hit balls past nets and one another.

Tennis itself dates to the 16th century, although its handball predecessors stretch back to the 1100s, around the same time Ghengis Khan was born. Like every sport, it evolved and changed over the centuries. Henry VIII enjoyed playing it indoors, as was the custom then.

By the late nineteenth century the sport had moved out onto the croquet lawns of clubs and estates. The first championships at Wimbledon took place in 1877, exactly a century before the introduction of the Atari Video Computer System, a video game system whose hardware was designed for games like Pong.

Yet in the time hence, no match like that of Isner and Mahut had been played, despite the fact that it came about thanks to a relatively simple and obvious consequence of the sport's rules.

Men's matches at Wimbledon are won by capturing the best of five sets, each set requiring six games to a side for victory, by a margin of two. In all but the final set, a tied score of 6-6 is decided by a tiebreak game (itself an invention of the 1950s). But the fifth set is not eligible for resolution by tiebreak, and play continues until one player bests the other by two games.

It was this chasm into which the unknowns Isner and Mahut fell, neither able to break the other's service and thereby tip the match out of equilibrium. The players served over one hundred aces each, evidence for the levelness of their ability. Isner finally bested Mahut with a 70-68 final set, figures that exceed the score at the buzzer in this year's NCAA basketball final.

The Isner-Mahut match exemplifies the familiar unfamiliar. The sport of tennis is well-known and well-explored. Its scoring mechanism is no secret, and it has always been possible for a match to go on as long as this one did. But just as no one had ever found inspiration and opportunity to perform a behind-the-board reverse layup before Julius Erving did in the 1980 NBA finals, so no fifth set had extended as long as Isner and Mahut's well-matched service games allowed.

It didn't matter that Isner was dismissed from the tournament the next day in straight sets, for he'd helped reveal something about tennis far more weird and beautiful than the mere ability to win a match or a tournament could ever show.

Dr. J's famous play had offered a glimpse into virtuosity, but Isner and Mahut's match offered something different and subtler: an essay in balance. Over three days they gave the world a guided tour of the curious collision of the two-point margin, mutually strong service, and closely-matched endurance. A tennis match, it turns out, could go on forever, dancing with itself into infinity like a binary star.

Imagine if tennis worked like video games. Every five years, the latest gizmos dreamed up by clean-cut French and British engineers would be revealed ceremoniously at Roland Garros and the All England Club -- electrified force fields on court boundaries, perhaps, or a charged ball to be used with a racquet-replacing glove capable of electromagnetic induction. A surface of ice instead of grass or clay, or of lava, with Nike-branded impermeable boots allowing players to vault from contracting to expanding hunks of igneous court.

To be sure, the results might be awesome. But that new awesomeness would likely never produce a result like the Isner-Mahut match, which required a century of championships on and off the grass courts of Wimbledon to reveal itself. It is only now that we realize, for example, how strangely strong and fragile the game of tennis really is when placed in even hands, like a soufflé that somehow survives on the line of scrimmage.

There is thus a virtue in familiar, well-trod platforms like the grass courts of Wimbledon. While they hardly exude the novelty of the next big thing, the rhythm of their longevity brings about new explorations of seemingly familiar spaces.

When new console platforms or controller gizmos or sensor upgrades or operating system revisions appear as frequently as they do for video games, we never even get a chance to plumb the depths of our old ones.

Instead, we maintain the collective hallucination that technical unfamiliarity is an equivalent to unfamiliar familiarity.

The result is all too familiar indeed: familiar characters commit familiar acts in familiar places -- but in slightly unfamiliar ways, or using unfamiliar display technology, or by means of unfamiliar interfaces. These are the sitcoms of game design, and they have their place. But must their place be the only one?

Of course, some designs do live on despite the gizmo crusade that motivates them. Genres and conventions evolve from technology to technology, making subtle shifts even despite often being deployed in the interest of a familiar franchise. And unfamiliar takes on familiar work sometimes emerge from technical provocation. After all, Pong taught us something new about tennis (table tennis anyway), by having a simple circuit design that effectively restricted movement to the baseline.

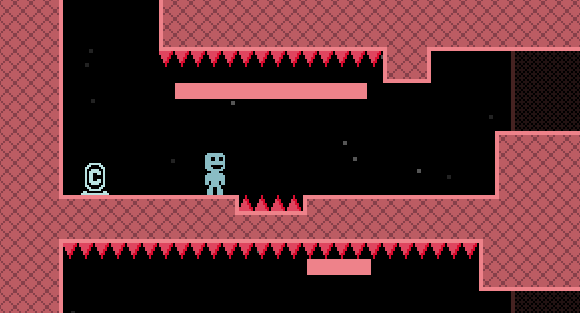

VVVVVV

Can we imagine plumbing the depths of the Mario bros., rather than just sinking them into yet another set of iconic pipes? Games like VVVVVV offer examples of plumbing the depths of a mechanic (in this case, gravitational reversal). And for what it's worth, it does so without 3D goggles or motion controllers.

It is a game that could have been made on a ZX Spectrum or a Commodore 64, a fact laid bare by creator Terry Cavanagh's brave refusal to update its graphics for contemporary eyes. But mechanical depth is just one way to experiment with unfamiliar familiarity in games.

Additionally, like Isner and Mahut, we could immerse ourselves entirely in a platform or an interface or a genre or a convention, refusing to come to the surface until we'd found new treasure in its murky depths, dismissing new attachments and upgrades as dangerous distractions, holing ourselves away like athletes practicing one dense corner of our craft to mastery.

It's a stance that seems almost unthinkable today. After all, the industry as a whole refuses to believe anything new and worthwhile and surprising could yet emerge from the Atari or the Dreamcast or the 8-directional joypad or the tilemap. Of course, until recently, that's what most people thought of tennis's fifth set too.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like