Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In his latest 'Persuasive Games' column, game designer and writer Ian Bogost examines both Natal-like gesture control devices and Brenda Brathwaite's experimental board game Train, suggesting: "Perhaps the souls of our games are not to be found in ever-better accelerometers... but in the way they invite players to respond to them."

[In his latest 'Persuasive Games' column, game designer and writer Ian Bogost examines both Natal-like gesture control devices and Brenda Brathwaite's experimental board game Train, suggesting: "Perhaps the souls of our games are not to be found in ever-better accelerometers and infrared sensors, but in the way they invite players to respond to them."]

Games have flaunted gestural interfaces for years now. The Nintendo Wii is the most familiar example, but such interfaces can be traced back decades: Sony's EyeToy; Bandai's Power Pad; Mattel's Power Glove; Amiga's Joyboard; the rideable cars and motorbikes of '80s - '90s arcades; indeed, even Nintendo's own progenitors of the Wii Remote, like Kirby Tilt 'n Tumble for Game Boy Color.

Recently, all three major console manufacturers announced new gestural interfaces. Nintendo introduced the Wii Balance Board last year, a device capable of detecting pressure and movement on the floor. This year, the company released Wii MotionPlus, a Wii Remote expansion device that allows the system to detect more complex and subtle movements.

At E3 2009, Sony demonstrated prototypes for the PS3 Wand, a handheld rod that uses both internal sensors and computer vision, via the PlayStation Eye camera, to track and interpret motion.

And Microsoft announced Project Natal, a sensor system that foregoes the controller entirely in favor of an interface array of cameras and microphones capable of performing motion, facial, and voice recognition.

With few exceptions, designers and players understand gestural control as actions. Lean side to side on the Joyboard to ski in Mogul Maniac. Grasp and release the Power Glove to catch and throw in Super Glove Ball. Bat a hand in front of the EyeToy to strike a target in EyeToy: Play. Lean a plastic motorbike to steer in Hang On. Swing a Wii Remote to strike a tennis ball in Wii Sports.

Gestures of this sort also strive for realistic correspondence of the sort advocated by the direct manipulation human-computer interaction style. Input gestures, so the thinking goes, become more intuitive and enjoyable when they better resemble their corresponding real-world actions. And games become more gratifying when they respond to those gestures in more sophisticated and realistic ways.

Such values drove the design of all of the interface systems mentioned above: MotionPlus, Wand, and Natal all involve high-resolution technologies that hope to capture and understand movement in more detail.

Physical realism is the goal, a reduction of the gap between player action and in-game effect commensurate with advances in graphical realism. As one early review of MotionPlus put it, "It's like going from VHS straight to Blu-ray."

As much as physical realism might seem like a promising direction for gestural interfaces, it is a value that conceals an important truth: in ordinary experience, gestures not only perform actions, they also convey meaning.

Consider body language. According to an oft-summarized but infrequently cited study (psychologist Albert Mehrabian's 1971 book Silent Messages), half of human communication takes place through non-verbal actions.

Gestures like crossing one's arms, tilting one's head, and rubbing one's forehead telegraph important attitudes and beliefs. In these cases, gestures are intransitive; they do not perform actions.

Instead they signal ideas or sensations: impatience, disbelief, weariness, and so forth.

Other gestures take indirect objects. When we wave hello or flip someone the bird, we do not alter the physical environment in the same way a racquet does when striking a ball or a hand does when grazing a pool. We may, however, change the way the recipient of the gesture thinks or feels about us or the world in general.

(Lionhead's "Milo" demo for Natal offers one approach to such a goal, although it apparently uses vocal recognition over gestural recognition; hand gestures once again become actions, like reaching in to disturb the surface of a pond.)

But gestures, be they transitive or intransitive, direct or indirect, can also alter an actor's own thoughts or feelings about the world or himself. These sensations can be complex, and they can evolve. Flipping someone off may impress delight, then guilt, then shame. Reaching into a clogged drain may instill dread, then disgust, then relief.

One game that implements gestures in this way is Manhunt 2 for Wii. Recall the controversy this game spurred at its release in 2007: it was nearly banned in several countries partly because it asked players to act out heinous acts of torture through physical actions.

Yet, the game's coupling of gestures to violent acts makes them more, not less repugnant by implicating the player in their commitment.

In Manhunt 2, we are meant to feel the power of Daniel Lamb's psychopathy alongside our own disgust at it. It is a game that helps us see how thin the line can be between madness and reason by making us perform abuse.

But gestures in Manhunt 2 are still descended from direct manipulation, swings and thrusts of a controller mapped roughly to torture. For a subtler, richer example of player gestures that imbue meaning through representation and evocation rather than direct manipulation, we must consult a more unusual sort of game.

Brenda Brathwaite's Train is a tabletop game, one of six that the veteran designer is pursuing in a series on difficult subjects.

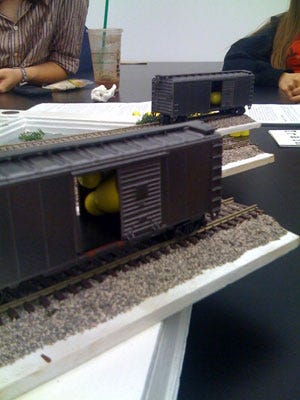

Train's game surface is a window, some panes broken, with additional broken glass scattered atop the surface of the play area. Three railway tracks extend at oblique angles across the width of the window.

The object of the game is to load yellow people tokens into boxcars and to move them from one end of the track to the other. Players roll dice to add passengers and move trains forward, and they draw cards to execute other actions, such as switching tracks, damaging a train, and derailing. Terminus cards on each track reveal each train's destination at the end of the game: Auschwitz, or another Nazi concentration camp.

Because it exists in one edition only, far fewer people have played Train than have discussed it. When The Escapist published coverage of Brathwaite's discussion of her series at the Triangle Games Conference, a number of readers (among them industry veterans Ernest Adams and Greg Costikyan) wondered if the game mostly offered a "shocker ending," to use Adams's words.

On first blush, the dread and disgust and horror Train dispatches may seem like a trick of implementation, not an experience delivered through the playing of the game itself.

Yet, when one actually plays Train or watches others play it, its emotional power shifts from the epiphany of its ending to the individual gestures that construct its play session -- gestures that must necessarily be enacted in order to reach that finale.

Photo by Geoff Long. Used with permission.

For example, players may add people to their boxcars. It is a simple act, one that might entail pointing and clicking in a PC or console game. But to do so in Train, players must insert the wooden tokens into the narrow doorway of the boxcar.

How to accomplish this feat is entirely up to the player -- he might leave the train on the track and attempt to insert the token into the side. Or he might pick up the entire car, godlike, and drop the token as if it were an insect.

Adding additional tokens requires tilting or otherwise upsetting the car to make it possible to cram more people in. This is a disturbing experience, and players seem to alter their gestures of passenger loading and unloading as they better understand their implications.

Removing passengers at the end of the track requires similar physical investment. The tokens barely fit through the boxcar doors, and removing them is difficult. It's hard to avoid picking up the boxcar and shaking it against an open palm to remove tokens.

The moral and historical significance of these gestures, individually and collectively, is not lost on Train players or spectators. The game not only forces the player to manhandle people, it also forces him to figure out how to do so.

In so doing, the sense of complicity which at first seems tied only to the game's ending creeps anxiously into every action the player performs.

Simple, trivial acts like picking up game tokens or moving pieces along the board take on rich multiplicities of meaning in the minds of players and spectators alike thanks to the game's striking ambiguity. In this game, the action one performs is important as such, not just in relation to the outcome it produces.

The relevance of gameplay gestures can be found in aspects of Train that have little to do with the progress of gameplay. For example, sometimes players have the opportunity to remove tokens from opponents' boxcars.

The game never tells the player what to do with these tokens, so one could just as easily hide them in a pocket, "saving" the victims, as one could return them to play. One might even choose a different method of removal in an attempt to signal contempt to an opponent, a gentle touch that says, implicitly, "let's stop."

The game's setup engenders gestural significance as well. At its start, the yellow tokens are lined up in rows at the side of the table. As players reach for people to stuff into their boxcars, these neat rows become disturbed, uneven.

Even as a spectator, participants may find it difficult to resist "fixing" these disorderly lines of people, returning them to a more uniform and stable state. Here we find a gesture that bears meaning even if it is not consummated.

The sinking feeling that accompanies it is palpable -- one cannot help but admit that there is a measure of comfort in extreme order, and that such comfort is one tiny pebble in the foundation of fascism.

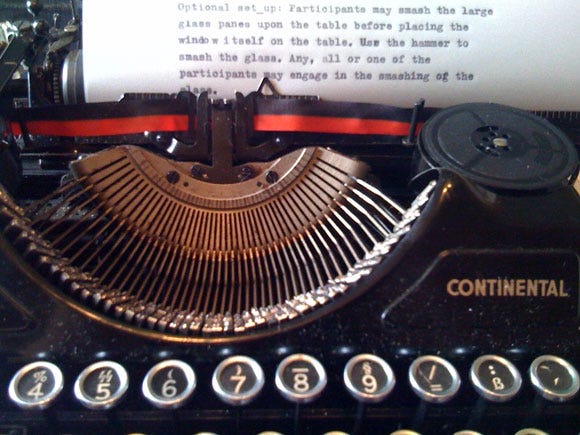

Even the game's rules impart gestural meaning. The rules are intentionally ambiguous, and players will find themselves referring back to them frequently. Brathwaite managed to acquire an authentic SS typewriter for the game (complete with SS sigrune above the 5 key), which she used to type up the rules.

These sheets are placed in the typewriter at the start of the game. In order to read or review them, players must get up and face the typewriter, turning its knobs to reveal the desired text or to remove the sheets.

As one leans in to read the page or to handle the typewriter, game rules instantly become military orders. One cannot help but allow sensations of loyalty and treachery, pride and disgust to well up with each click of the typewriter platen.

Train offers an important lesson in physical design: the way a player responds to a gesture is at least as important as the way the game responds to such a gesture.

But Train is a tabletop game, not a digital one. Is it even possible to translate the gestural ambiguity of such an experience into a video game?

The answer may lie not in Train's form, but in its method. The game embraces ambiguity at every turn, refusing to connect any dots. It never makes an argument about the Holocaust.

It never even takes a position on whether or not the efficient movement of people from station to terminus ought to be praised or condemned by its players, whether they should adopt the role of Nazi officer in order to grasp his plight or if they should reject it as morally reprehensible.

Instead, the game creates a circumstance in which the gestures a player performs -- lining up passengers, loading and unloading them, moving trains to a death camp -- are allowed to reverberate uncomfortably.

One of Will Wright's contributions to game design is his elevation of ambiguity to a first-order design principle.

Even in simulation-heavy games like SimCity and The Sims, players are afforded tremendous interpretative freedom as they imagine what's going on behind the walls of their buildings or in the minds of their sims. In simulation, abstraction doesn't just simplify implementation, it also affords richer experience.

The same might be true of gestural interfaces. While increased physical realism might allow actions to become more faithful in their specificity, compelling significance doesn't necessarily come for free. Indeed, by abstracting a game's response to gestures, games of all kinds can allow the player a richer interpretative field. And in many cases, interpretation is more interesting than responsiveness.

Consider a much less politically charged example: Dance Dance Revolution. DDR's success as an arcade title comes partly from its honed responsiveness to simple player steps. But its life as a venue for public performance was born from the spaces the game didn't measure between steps, spaces players felt compelled to fill with improvised maneuvers of their own.

Train might then invite questions about the mad dash toward new and improved gestural technology. Wii MotionPlus, PS3 Wand, and Microsoft Natal all assume that higher resolution, greater fidelity inputs will result in more compelling games. And they will, in part; certainly the precise physical properties of Train are intrinsic to the gestural meaning they impart.

But the speed of development and release of new hardware platforms also offers excuses not to explore the tools we already have.

Perhaps the souls of our games are not to be found in ever-better accelerometers and infrared sensors, but in the way they invite players to respond to them. After all, Brenda Brathwaite was able to plumb the depths of dread, exploitation, and complicity with wooden tokens and plastic trains.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like