PAX East Report: The Shrouded Isle and embracing darkness in games

This year, a subtle current among the indie games on display at PAX East was exploring life in cults from the inside.

PAX East’s indie offerings sometimes have unexpected themes emerge from the potpourri; a couple of years ago it was young women as detectives. This year, a subtle current among the games on offer was exploring life in cults from the inside.

The Church in the Darkness offers a Wolfenstein-influenced experience of infiltrating a Jonestown-esque cult in the 1970s, throwing narrative choice into the mix as well as offering a choice between peaceful and violent interaction.

There’s a lot to be said for the influence of subjects and settings on the mechanics of a game, structuring the meaning of your actions as a player and influencing how you approach the game world.

The Church in the Darkness dwells in a new, unexplored place: exploring why people might join a cult. Scientology has been taken on by both The Secret World and Knee Deep, but both were very much outside-looking-in perspectives rather than all consuming investigations of what a cult’s way of life means to the people most deeply enmeshed in it.

Church is taking a different route, with implications for understanding contemporary political dynamics as well.

The Church in the Darkness

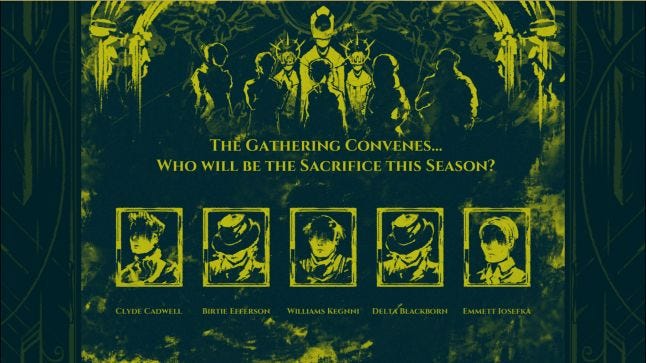

Another game that dwells in darkness so deep it lacks color altogether is Kitfox Games’ latest venture The Shrouded Isle, which takes a somewhat more fantastical approach to the idea. Here you play in a Lovecraftian world as the High Priestess of a seaside village cut off from the rest of civilization.

You are but five years away from the return of the tentacular Chernobog, the object of your devotion, and you must keep the increasingly restive familial houses of your village in line. Oh, and you have to pick a human sacrifice once every season to feed your Old God the human blood he thirsts for.

The version I played was essentially pre-alpha and thus I only got to play through two seasons--Spring and Summer--to get a very basic sense of the game’s flow. But while I rarely complete game demos at conventions, either due to constraints of time or lack of interest, I made it all the way through Shrouded Isle’s.

The interface puts one in the mind of resource management sims and some visual novels like Hanako Games’ Long Live the Queen where you’re trying desperately to balance wildly competing stats. Here, you’re trying to manage your village’s adherence to Chernobog’s five virtues: Ignorance, Fervor, Discipline, Penitence, and Obedience.

You do this by assigning representatives from up to three of the five great houses to act as your enforcers throughout the season, but each has a vice that will lower another virtue. The trick seems to be finding a way to investigate as many people as you can--which consumes in-game resources--so you can better predict what their impacts will be on the village’s disposition.

Discovering vice is vital because it helps you decide who will make the best sacrifice. What I love about the game is that it shows how secular politics persists, even in a cultic community where fundamentalist dogma pervades all aspects of life.

The great houses vie for influence, or may even reach a point where they are contemptuous or rebellious towards your rule as High Priestess. Your selection of a sacrifice is not infallible--it has political fallout. Whichever house was culled this season will likely resent you for it; doubly so if you’ve uncovered no proof of a serious vice.

What’s intriguing about this is how it shows the persistence of humanity in an inhumane environment. Even in those social groupings that specifically exist to grind individuality, freedom, and personal expression into an indistinct mulch, that messiness persists.

It’s a critical lesson for developers who want to set their games in some morally perverse environment; evil is never so absolute as to bring everyone in line. This lends a precious insight for those looking to make games set in totalitarian regimes, say.

It’s also smart from a mechanical perspective. The politics of Shrouded Isle provides the frisson of challenge. The game would be far less interesting from the player’s perspective if everyone was so absolutely devoted to Chernobog and your rule as his representative on Earth that they gleefully went under your sacrificial dagger. Keeping personal, secular politics in this realm richly populates the world with mechanical challenges that entice the player.

The Shrouded Isle does have a ways to go. One of the problems in its current state is the opacity of investigation mechanics--and perhaps a paucity of them, as well. You need to find ways of investigating villagers to uncover whose vices are so terrible as to ensure everyone will be satisfied with their execution, but there’s little direction on this from game, and not much in the way of instruments to aid you.

It left me essentially stumbling around, all but committing to getting one house really angry at me because I needed to kill someone. That may be the point: forcing the player to start the game in a desperate deficit of goodwill that they will have to fight to overcome.

Thrashing to keep your head above water seems appropriate for a High Priestess of an old god. But if that’s a deliberate theme, there’ll have to be some more elegant finessing to get it to stick the landing without frustrating players.

Either way, Shrouded Isle is taking us to a dark place. These are certainly desperate--and perhaps dangerous--times to be exploring why cults and cultic thinking tickle the fancy of so many. The Church of Darkness explores a cult with a strong left wing bend, the Collective Justice Mission. Is that relevant as anything other than nostalgia in an age of far right, even fascistic resurgence? Perhaps.

Honest, immersive gameplay about the allure of extremism, of any sort, could be instructive in our current moment. Even more fantastical offerings teach us something about humanity’s endurance in the most colorless of worlds.

Right now, that’s oddly hopeful.

Katherine Cross is a Ph.D student in sociology who researches anti-social behavior online, and a gaming critic whose work has appeared in numerous publications.

Read more about:

2017About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)