Opinion: Reflections on Tacoma

"The writing kept me floating from one section of the station to the next. If Fullbright excels at anything, it’s at setting. Mood, character, expression, tricks of the light, are all there in spades."

I think I truly understood Tacoma’s interactivity when I realized that eating while playing was a terrible idea. It’s very mobile in a way you quickly take for granted, and it’s hard to notice unless you’re trying to do two things at once with your hands, as I was. But there I was, rushing to put down my chopsticks and start running after the AR hologram of a crew member who was walking and talking.

If there’s a core mechanic that holds up Fullbright’s Tacoma like a spinal column, it’s that you have to literally follow a conversation. As you’re exploring the empty space station, trying to figure out what happened, you have to play back three dimensional augmented-reality recordings of crew conversations that capture both their dialogue and motility. Often, getting the full picture means wandering off after someone who peels away from the conversation--they bump into someone else and have a side chat, or start talking to ODIN, the ship’s AI.

One way or another, you have to move. There’s no room to drift; you’re always involved in the moment.

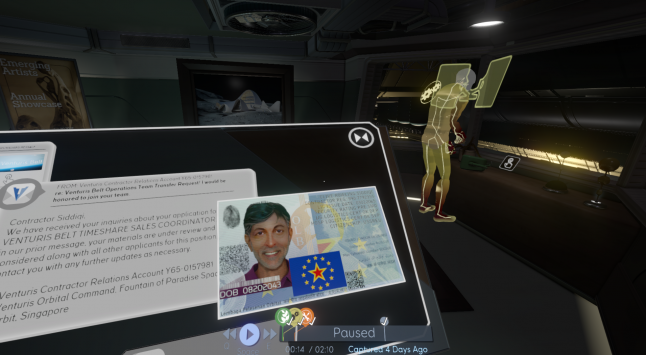

You also have to keep an eye out for when they summon up their own AR interfaces--like a newspaper that unfolds in front of them--which you can scan for emails, text chat, and the websites they were looking at. I found this particularly elegant. Instead of having computer terminals all over the place that you pecked at to read an email that just happened to be on screen, it’s all folded right into the AR recording system. Every crew member’s personal computer is — after all, in their heads in 2088. It’s a nice way of allowing you to indulge the adventure game mainstay of rifling through someone’s letters, but in a way that feels expressive of the setting.

All of this requires a lot of movement and being quick-fingered on your keyboard to strategically pause, rewind, or fast forward the AR playback. It’s hard to say it isn’t interactive, and something would surely be lost if this story weren’t told through the medium of a game. It’s also more interactive than its predecessor, Gone Home, in that there are simply more things for you to unlock.

"If Fullbright excels at anything, it’s at setting. Mood, character, expression, tricks of the light, are all there in spades."

Usually you don’t have to find the codes and keys that let you unlock various bits of the story; you can progress without them. But it’s essential to fully understand the evolving story and its characters, all of whom I fell in love with to some degree or other. The writing, after all, is what stands head and shoulders above everything else. It kept me floating from one section of the station to the next, a digital page-turner if ever there was one. If Fullbright excels at anything, it’s at setting. Mood, character, expression, tricks of the light, are all there in spades.

I empathized perhaps a little too deeply with the station’s doctor, Sareh, and its ops manager, Clive. The assemblage of logs, recorded conversations, and personal effects created a mirror-like mosaic for me, and it’s hard not to wonder at how many other people might’ve felt the same way--like they were seen by ODIN’s lidless eye. It makes the cost-saving choice of using wire-mesh blobs as the AR stand-ins for all the characters seem rather clever, in the end. They’re featureless, but all have distinct shapes and mannerisms that convey a surprising amount of information when combined with the brilliant voice acting. They focus your attention on what matters for the story the game is trying to tell.

On that note, I realized as I played through the story that none of the principal characters were white men, a remarkable thing when a white male “audience stand-in” is still considered de rigueur in most entertainment media. It’s a rare and risky thing for a game like this to do, but it pays off by providing us with a wonderful story that shows empathy can transcend such demographic barriers. Tacoma’s cast hails from the world over, in a future where borders have sometimes dramatically been redrawn (god only knows what the story is behind the “USSREU”), and yet each is easy enough to relate to.

In any event, as a thematic matter, it was wonderful to see how successfully Fullbright went beyond the hipster 90s nostalgia of Gone Home--a theme that’s become rather tedious and overdone, of late. Their literary talents shine in genre fiction, and I’m glad they took a gamble on this sci-fi adventure.

***

A lot changed from the version I first played nearly two years ago, which appears to have been almost entirely scrapped. “Virgin-Tesla,” as the name of the station’s corporate owner, was no more (too hot for the lawyers, one guesses), replaced by “Venturis Technologies.” Gone was the attempt to make little puzzles out of zero-G navigation, and the idea of Tacoma as a luxurious transfer station for the super-rich on their way to a lunar resort. Gone, too, was the once iconic gilded vestibule garden you entered the station by, now relegated to a framed portrait in one of the crew member’s offices.

Though the original idea was always for the game to take the player into the “backrooms” of the station where the workers actually lived, away from the fancy parts of the station patronized by the rich holidaymakers, that peek backstage has now become the full game in the final version. No more golden space toilets, alas. But the result seems more fully in line with the themes Fullbright wanted the game to have, of orbital workers chafing against the dictates of a bloodless corporation that would rather see them replaced by AI.

That required a way to show personal space, to play to their strengths in environmental storytelling--something that physics itself would’ve obviated in zero-G. “People sleep in sleeping bags tacked to the wall, they stick things to Velcro strips, they let things float around near where they hang out,” Fullbright’s co-founder Karla Zimonja told me, “What they totally don't do is use tables and chairs in normal-G ways, or personalize their environment in ways we're used to or can easily grasp. And we needed that stuff! We wanted to be able to show people's living spaces and have them make sense to the player, and that was just much much harder without centripetal gravity.”

"As is always the case with heavily narrative games like this, what they lack in mechanics they have to make up for in interiority."

Zimonja added that this need for personal space was the reasoning behind moving away from the idea of a Tacoma with a gilded front-end. “The change from fancy lobby for rich people to a cargo transfer station was made for a similar reason as the gravity thing -- it gave us more personal spaces. If a space is a big fancy ballroom or casino, it can be lovely but no one can live there, you know? Lived-in spaces are absolutely necessary for us, so we realized we had to do some rethinking!”

The worldbuilding that results is quite evocative and even a bit chilling, lending these lived spaces some pressing context. Currency as we know it has mostly been supplanted by corporate Loyalty. Think of it like an airline rewards program with points, except for everything, tied to your employment by a particular mega-corporation. The gig economy has been replaced by a corporation taking ownership of you from birth to death; go to the corporate university, join the corporation, earn corporate scrip all your life with added bonuses along the way at critical reward tiers. Everyone owes their soul to the company store, here.

The loss of zero-G play is regrettable, preserved only in a much more limited form when you’re floating through the station’s hub. But everything else seems pared down in a way that better conforms to the game’s core ideas--people trying to get by, desperation after a disaster, love in the wrong places.

As is always the case with heavily narrative games like this, what they lack in mechanics they have to make up for in interiority--more of the game has to be played in the player’s head, in other words. Our emotional response must become part of the play, and by this measure Tacoma certainly succeeds.

The game needed to deliver an experience that coiled tight around the emotions it was trying to elicit from us, and it succeeded. The overall result doesn’t advance the genre much beyond the ground staked out by its predecessor, but it still shows a lot of flexibility and creativity on the part of Fullbright. Tacoma’s is a world worth revisiting for its universe of personal detail. There’s much more I could add, but that would require spoiling the game in ways that merit a separate article. It’s sufficient to say that Tacoma works well enough to keep me going back. After the long wait, I wasn’t disappointed.

Katherine Cross is a Ph.D student in sociology who researches anti-social behavior online, and a gaming critic whose work has appeared in numerous publications.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)