Opinion: 'Interactive fiction' is just another way of saying 'game'

Columnist Katherine Cross applies a critical lens to the old game/non-game debate surrounding interactive fiction.

"Okay, it's fun, but is it a game?"

Whenever there is debate about whether any particular game can rightly be called a "game" it swirls, often as not, around anything that can be lumped into the "interactive fiction" genre; it should, come as no surprise that IF is experiencing something of a renaissance on mobile devices, a platform often maligned by hardcore gamers.

But I often find myself thinking of Chris Franklin’s words on the matter: "The 'game/non-game' debate ends up limiting the scope of games themselves. When we say that dys4ia isn’t a game, we’re saying that games can’t provide that experience." It may be the single most effective argument against the entire tedious debate, but it also provides a useful critical lens that can help us understand just how revolutionary some of these games actually are. What are these games allowing us to experience?

***

The use of words in lieu of graphical representations is often seen as a limitation; a concession to low (or nonexistent) budgets and a pale imitation of bigger, supposedly better games, that would never commit the unpardonable sin of forcing the player to imagine the world they play in.

But the immersive effect of games is something that avails itself of its particular medium; text may not envelop you in the same way as a photorealistic graphicscape, but it surrounds you and sets your mind ablaze all the same.

I could make appeals to how such games harness the richness of the novel or short story for ludic adventures, but I can do one better by pointing to a title that, in a first for games, is doing something unique with words-as-such.

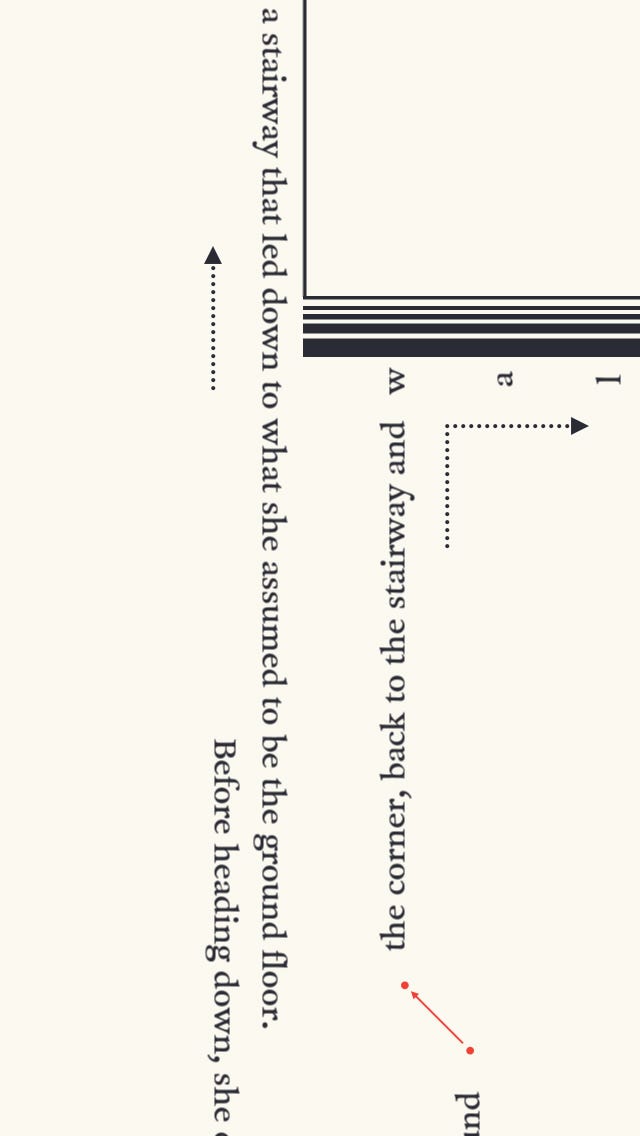

Simogo’s Device 6, which is tragically iOS-only, manages a splendid fusion of Myst-style adventure gaming with the interactive fiction form, and the level of involvement is stunning considering that the narrative is linear. “Choice” is often one of the selling-points of IF games, and often where its defenders locate its ludic essence. The fact that the player decides how to proceed is seen as crucial to separating such games from, say, e-books.

But Device 6 shows us another way. You see, the text proceeds in the direction of the protagonist’s perambulations, filling rooms and thinning into tight corridors or twisting into spiral staircases like a vapor made of Times New Roman. You twist and turn your tablet to read the text upright, matching Anna’s winding paths on the mysterious island she’d awoken on. It involves you in her motion in a way that similar titles don’t, simulating the feel of actually being in this environment. There are visuals, but most are static and act as narrow windows through the text that one must often search for clues.

Further, between each 'chapter' is an eerie survey, providing the one moment during the game where you make choices. It's a strange pause that blurs the line between the game's reality and your own. The fact that you have to hold your device, be it a tablet or phone, in order to do this and follow instructions that encroach on the physical ("hold your ear and press this button" "hold the tablet six inches from your face" "lay your device on a flat surface") implicates and involves you in a way I've rarely felt with other equally creepy games.

There are many chilling novels out there, and many horror games, but Device 6 merges the signature experiences of both in a way that extends the game's remit into your own body, making it that much more impactful. It simply could not exist on a computer screen or a television; it demands your physical involvement, your touch.

Yet it's still mostly text.

***

Read Only Memories 2064, soon to be released by Midboss, is more traditional--no screen twisting or creepy surveys about insects required--but also shows brilliantly what interactive fiction is capable of. The cyberpunk game follows the tale of Turing, an adorable AI who just so happens to be the world’s first sentient robot; you play a Neo San Franciscan journalist who’s down on their luck and is enlisted to find Turing’s kidnapped creator, Hayden.

Like Device 6, the game is punctuated by occasional challenges that test one’s skill--a creatively programmed taxi chase that sees you hack into Neo SF’s traffic grid manages to be both lo-fi and stimulating-- but it also makes a game of the text itself.

Though you do find uses for your low-powered laser sidearm throughout the game, the true final boss of the ROM2064 is not a person but a conversation. You must demonstrate how well you’ve come to know a certain character by making appropriate dialogue choices that arise from both your relationship and your experiences throughout the game.

Choosing the right words makes a mechanic of a rather interesting thing: empathy. The stakes are impossibly high and, for once, you can’t depend on violence to even the odds.

As a player, a skill you must cultivate throughout the game is simply getting to know the people you meet, and responding to them less like vending machines that dispense objectives, and more like actual people. That theme culminates in the game’s final moment to great effect.

***

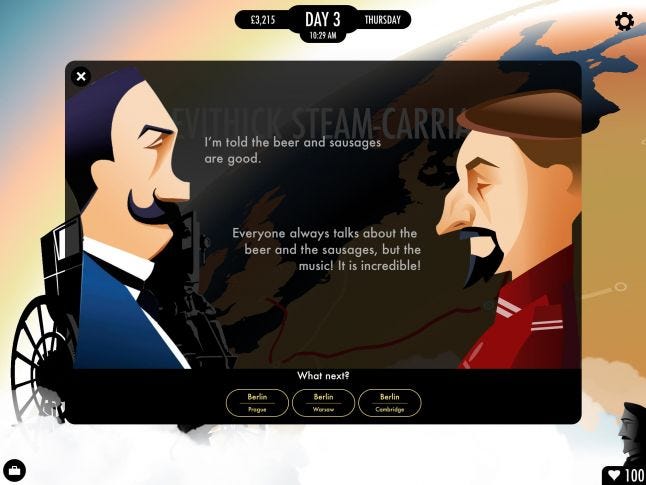

Text can unfold linearly, with swishy screen rotation; or it can do so laterally in a maze of possible paths, as in inkle’s 80 Days, where a literal world of adventure sprawls out from a steampunk London in a fascinating reinterpretation of the Jules Verne classic. The narrative spreads like a blossoming inkblot from writer Meg Jayanth’s pen, player choice combining with resource management and dialogal attentiveness to fashion an addictive adventure that’s seen me circumnavigate Inkle’s beautifully rendered globe many times over just in the last day.

The kind of story that your adventure tells depends on the direction you take, each city, every market, every dialogue choice sending you off in a variety of paths; you could have a Shackleton-esque drama over the North Pole, or your adventure could be a romance, or perhaps being a revolutionary is more your speed, or maybe a James Bond-esque spy (but with a waxed mustache, of course). The point is that here, interactive fiction is used not only to tell a branching story, but to combine several genres in a single game to create a renewable experience not quite like anything else I’ve played.

What links 80 Days, Device 6, and Read Only Memories 2064 is that they demonstrate particularly inventive ways to turn words into games, with lessons for any developer. Words can paint a geography through their very shape, as in Device 6, and can gird the use of the very platform your game is playing on to suspend the player’s disbelief. They can be used to make mechanics out of aspects of conversation and personal interaction, as in ROM2064, in ways that are neither shallow dice rolls nor "vending machine" style interactions. They can also be used to extend the versatility of the game’s genre, as in 80 Days, allowing replayability along wildly different narrative lines all in the bounds of the same title.

***

In short, far from being an aberration or milquetoast distraction, interactive fiction demonstrates just what kinds of new experiences games are capable of producing, and provide powerful examples of narrative in literal action.

In short, far from being an aberration or milquetoast distraction, interactive fiction demonstrates just what kinds of new experiences games are capable of producing, and provide powerful examples of narrative in literal action.

There is a final link, too, between Device 6 and another mobile series: Lifeline. Both Lifeline and its sequel Lifeline 2 (Android and iOS) are entirely text based, lacking even the still images of the other games I’ve mentioned here much less the lively pixel art of ROM2064, but the conceit of the game staggers: you are somehow communicating with an imperiled person through your mobile device.

The first game sees you contacted by an astronaut stranded on a distant planet, and only you can use the eponymous lifeline to bring him home, the second sees you contacted by a woman in a fantasy universe on a quest to avenge her family. Each protagonist depends on you, involves you in their lives via the strange intimacy of their chance contact with you and even texts you with updates and requests for advice and aid.

You are left feeling as if you’re really communicating with them, despite the pre-arranged dialogue options, and like Device 6, its text is cleverly used to blur the line between your truth and their fiction. The very device you’re holding, through which you experience the game, is an artifact of the gameworld itself. Both games use the medium of interactive fiction to make themselves oddly diegetic, a quality that is vanishingly absent from far more lavishly designed titles.

If making you doubt your own reality isn’t proof that such titles are games, I can scarcely imagine what would be.

Katherine Cross is a Ph.D student in sociology who researches anti-social behavior online, and a gaming critic whose work has appeared in numerous publications.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)