Opinion: In praise of Tacoma's character Sareh Hasmadi

In a game peopled by rich characters whose failings and struggles were central to the story, Sareh Hasmadi stood out as exceptionally nuanced and human.

Courtesy of director James Cameron, we’re being treated to another tedious cycle of media discourse about what makes a “strong woman”--apparently we’re not allowed to have superheroines who show too much skin, and we needed a man to tell us this. The rules change far too quickly for me to keep up sometimes.

But it therefore seems as good a time as any to analyze a videogame character who, with the effortlessness of zero-G drift, rises above all this to show us how it’s done. Tacoma’s Sareh Hasmadi, the resident doctor aboard the eponymous space station, cut me quite deeply. As I played through the game a second time to hoover up the remaining achievements, the emotional aftershocks from my inaugural run came.

You see, after having sat with my feelings from my initial play through, it dawned on me that Dr. Hasmadi was largely their author. For in a game peopled by rich characters whose failings and struggles were central to the story, Sareh Hasmadi stood out as exceptionally nuanced, and human, in a medium where the latter is too often a rare achievement--especially where non-white women are concerned.

***

[WARNING: SPOILERS FOLLOW] I think it was in the Botany wing of the Biomedical Bay that I was hit the hardest. The AR memory you play back here sees the crew meeting to approve a daring escape plan--a normally unmanned delivery drone will be retrofitted to evacuate the crew to the surface of the Moon, while non-essential personnel go into cryogenic stasis to save oxygen. Andrew Dagyab, the station’s botanist, agrees only reluctantly.

As always, the AR recording presents you with multiple threads of conversation to pursue that spatially separate. You’ve got to do legwork to get the full picture. But this scene in Botany takes the mechanic to a high art through how it shows phases of emotion, and the way space shapes dialogue.

"Voice acting and animation combine here for a strong portrayal of a moment."

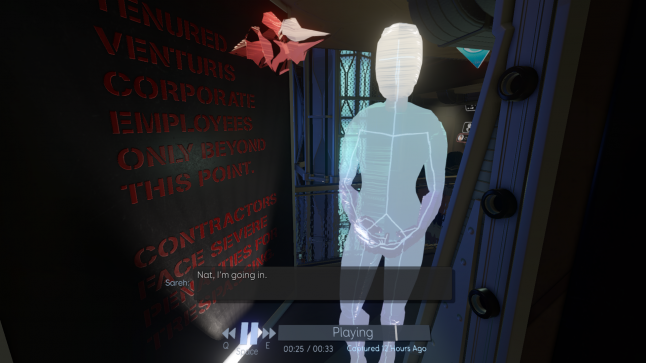

Sareh follows Andrew into a lower level room where he fumes at her about being “pressured” into agreeing with to the cryo plan, saying he won’t do it. Sareh is clearly blindsided but tries to console and reassure the man, already grieving for fear of never seeing his family again. Then she leaves and heads back up while he begins to put together a message for his loved ones. Alone upstairs, Sareh begins hyperventilating and ducks behind a door where she can be alone. With ODIN.

The ship’s AI, with whom she’d cultivated a warm relationship, walks her through her panic attack using breathing exercises and meditation techniques. Voice acting and animation combine here for a strong portrayal of a moment. It moved me; Sareh had been this confident pillar throughout the other AR recordings I’d seen, the aggressive fitness buff, the tough-minded critic with a commanding voice. Here, in this private space, with only ODIN as company, she wavered; her voice shook, before it deadened while repeating her mantras. Her animation showed a hunched, swaying figure, only slowly regaining its composure.

"Even well-intentioned portrayals tend towards a dehumanizing heavy-handedness. By contrast, I could see Sareh."

This moment was one I knew, all too intimately. It’s also hardly alien to fiction--we’ve seen strong characters have moments of vulnerability before. But there is, as always, an art to such things and it’s rarely mastered in videogames, where even well-intentioned portrayals tend towards a dehumanizing heavy-handedness. By contrast, I could see Sareh; I was Sareh, betimes.

For all her strength, there were moments in which she broke, and needed to slowly put herself back together. Suddenly all the anti-anxiety meds, yoga paraphernalia, and calming music strewn about her quarters makes sense. Every character in this game is “just getting by” in some sense; thus with Sareh.

“I am striding forward confidently upon my appointed path,” she says, almost monotone, under ODIN’s guidance, walking slowly towards that door to once again face Tacoma’s mortal crisis. The door opens, she runs into two of her colleagues, and without missing a beat talks to them as if she hadn’t been gasping for air moments ago.

"Much of the impact comes from moving through this social world in three dimensions; it’s used to great effect by Fullbright to lend a third dimension to its characters as well."

The simultaneity inherent to the AR playback mechanic is difficult to capture in the relentless forward-march of film, no matter how many Nolan-esque tricks one plays with timelines. It permits you to see what’s going on in many places at once, in all the privacies carved out by each of the characters.

You drift in and out of simultaneous conversations like a voyeur spirit, peeking behind locked doors here, manipulating time to catch precise moments. You have to move around in and poke at this space in time in order to get something out of it. All in all, it makes the case for this narrative being a game: the effect of a scene like this would have been qualitatively different in a linear medium.

Much of the impact comes from moving through this social world in three dimensions; it’s used to great effect by Fullbright to lend a third dimension to its characters as well.

***

Sareh fascinates me because she is a singularly tormented figure, who carries that burden in a way that is both humane and even, in the end, heroic.

Everyone on the station is fighting their own battles. Sareh’s is the death of a patient under her care at another space station, who somehow died from an operation to mend a broken femur--apparently due to a malfunctioning medical AI. Venturis Tech, which owns the station and the AI, wanted her to take responsibility; to take the fall. She refused, blunting her ability to advance in the mammoth corporation. But she remained determined to prove that the medical AI, HEKA, had a catastrophic failure that caused the death of her patient.

Sometimes to the point of prepossession.

"The way Tacoma expresses character sans-VO is quite impressive; a penumbra of emotion radiates from the text, and both the choice and placement of certain AR websites and chatlogs."

In her quarters, you can access her AR terminal and find it chock full of the blogs and photos of the travel writer who’d died on her operating table. Sareh pores over it all, wracked by guilt and fixation, while her chatlog with the station technical officer sees her pushing the limits of corporate policy to get information on HEKA’s record.

The way Tacoma expresses character sans-VO is quite impressive; a penumbra of emotion radiates from the text, and both the choice and placement of certain AR websites and chatlogs. Like so much else with Sareh, everything felt deployed for maximum splash impact. Such is the case in this scene, where she wordlessly dwells in an obsession.

But her pursuit of the truth behind HEKA wasn’t born of Luddism. More than anyone else on Tacoma, she saw ODIN as a person. She talked to him like an old friend, with the same surety that she approached her human colleagues. Alone among the crew, it is for Sareh that ODIN expresses a kind of emotion--trepidation that she may be reassigned away from the station. That relationship proves crucial later on.

Sareh had been reading up on AI, and flirting with the idea of getting in touch with the AI Liberation Front. In one AR recording, you see her chatting with ODIN while playing pool, and expressing disdain at how AI are kept segregated from one another, as it would be ‘disadvantageous,’ according to Venturis.

“Isn’t never meeting something else like yourself ‘disadvantageous’?” Sareh asks pointedly.

She saw sentient life behind that hologram, and in so doing, she helped save her crew.

***

If Tacoma were a film, all else being equal, Sareh would be its protagonist. After all, she is the one who is granted access to the AI core.

In both sci-fi films and games of this vintage, there’s always that part of the ship or station rich in futuristic secrets, where the climax lies. In Tacoma it was Sareh who was tasked with recovering those secrets, who saw what she was not meant to see, and who acted. In all the chaos, she emerged as the agent. She uncovered a conspiracy and she sent the distress call. She also knew she’d be turned into a scapegoat by Venturis, and indeed that’s the damage-control spin the corporation runs with in the game’s epilogue.

Through all her anxiety and torment, she screwed her courage to the sticking place. There aren’t enough female characters in games who are quite like this. Someone who is, at once, deeply vulnerable and strong at the same time, without being portrayed as vulnerable specifically because she’s a she. That sine wave of emotional fortitude is a very human thing indeed, and represents the difference between a character who’s just a thumbnail sketch and one who’s actually a character. Sareh was someone I empathized with, sometimes on a deep level.

If this is rare for women, it’s exceptionally so for women of color. Though the game doesn’t make a big deal of the matter, if you look through Hasmadi’s personal effects, you learn she’s a practicing Muslim. The details are there for those who look, but they also don’t overwhelm her character in stereotypes. Her swole fitness goals and her emergent AI politics matter more to who she is than her faith; as with most all non-white people, we are much, much more than our identity markers, but our cultures still have a grounding relevance that’s worth noting. Sareh’s culture is part of what’s shown to tie her to her family in Wisconsin, for instance.

At any rate, it’s a beautiful thing to see Tacoma present a cosmopolitan Muslim woman and doctor as the farsighted, if troubled, savior exploring the outer limits of technology. There’s a tightrope to walk in these portrayals, and Fullbright does it with aplomb (with all their characters, notably, about whom much the same could be said in this regard).

Especially in these dark days, the warmth and humanity of Sareh’s depiction is a much needed point of light. As a protagonist-like figure, she neatly expresses a theme endemic to all of Tacoma: that even in a grim, dystopian future, there is always hope to be found in the way people manage to simply survive. Sareh Hasmadi had been ground down and mentally tormented by a corporation that controlled almost every aspect of her life, and was suddenly thrown into the midst of a deadly conspiracy that seemed ripped from one of the thriller novels she read on her spare time; yet, conviction saw her through.

For Fullbright, then, the fact that people will continue to be people, in all our messiness and striving, means that there’s hope. It’s a message we surely need now, and one Sareh was perfectly written to deliver. She won the day, but will remain imperfect, haunted, and ready to assume a Warrior Two pose before her next challenge.

It is her appointed path, and where she is meant to be.

As with Gone Home, Tacoma is about the missing and the lost. You may ultimately learn the characters’ physical whereabouts, but you find they remain, to some degree, emotionally and spiritually adrift. Never quite safe, never quite done, still on the run somehow, gone again beyond the limits of a single, neat story. And that may be the most real thing of all in Fullbright’s games.

Katherine Cross is a Ph.D student in sociology who researches anti-social behavior online, and a gaming critic whose work has appeared in numerous publications.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)