Opinion: How Draugen lets down its characters

'At its best, this is a story that mints beautiful phrases in a heroically gorgeous setting,' opines writer Katherine Cross. 'But in the end Draugen shyly reaches for something well beyond its grasp.'

[Spoilers for Draugen follow; you’ve been warned, please don’t hurt me, I have a family.]

It seems there are no second acts in Norwegian life either.

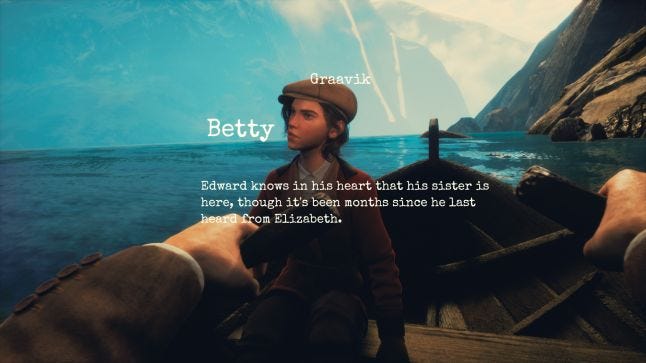

Red Thread Games’ anticipated Draugen transports the player to 1923, in the fictional village of Graavik, tucked into a Norwegian fjord, for an adventure to discover “what lies beneath.” Playing as the nebbish (if handsomely voiced) American scholar Edward Harden, you and your “gregarious and enigmatic young ward” Lissie explore the strangely deserted town in search of Edward’s wayward sister Betty, an intrepid and stylish journalist.

Graavik quickly reveals a litany of tragedies stretching back to the turn of the century, and a slow death that began long before Lissie and Edward set foot upon its shores.

At its best, this is a story that mints beautiful phrases in a heroically gorgeous setting. It is even moving at points, evoking themes of futility, isolation, and loss with stunning flashes of clarity. But in the end Draugen shyly reaches for something well beyond its grasp and its portrayal of mental illness leaves so much to be desired, especially when it is ultimately the fulcrum upon which the whole story is so precariously balanced.

***

The debt this game owes to Dear Esther is staggering: each features an eloquently sad man wandering in the beautiful desolation of northern solitude in search of a woman--and closure, as it turns out.

I’m on the cusp of spoiling the game but to be quite frank, the game’s biggest spoilers are blazingly obvious in the first few minutes of play. Careful attention to what is said and how will make certain truths abundantly plain by the end of the game’s first day. That’s hardly a sin, of course, but the nature of the spoiler might be.

After all, the great spoiler is Edward himself. About halfway through the game, it’s revealed that he has an unnamed mental illness that seems to be some blurry combination of schizophrenia and dissociative identity disorder. As is often the case with ham-handed portrayals that attempt to turn such things into “art,” the lines are vague and inexact. Lissie exists only in Edward’s mind, along with another character--The Entity, a thunderously voiced statue of a feminine angel.

What feels particularly noxious here is the reduction of a lived experience, an identity, to a “twist.” It’s on a par with the way trans identity is rendered such in films like The Crying Game, the semiotics of which always pervert a person into a stunning surprise you’re not meant to tell your friends about. That, of course, neatly reinforces the notion that such people should always be ashamed of themselves.

It would have been considerably more powerful and interesting if the game had been honest from the start so that we could be a part of Edward and Lissie’s journey in full consciousness of who they really were.

That brings me to the second twist, which attentive readers might have already guessed: Betty isn’t real either. At least, not strictly. She died as a child; Edward’s simply been unable to let go, inventing a whole adult life for her that saw him chase her across the globe. I won’t lie, there is a big part of me that deeply regretted the fact that Betty, the cosmopolitan flapper Lois Lane, wasn’t even diegetically real. But that’s only the start of the thematic issues here: every woman of significance to the story is bent towards either motivating or healing Edward. Betty is a strangely fridged figure, a dead girl alchemized into something that can’t exist just to give the entire game (defined by Edward’s journey) a reason for existing. Meanwhile, Lissie is brilliant: a spinner of many witty lines in delectable '20s slang whose personality is at turns willful and compassionate. But she is ultimately a helpmate for Edward--and, by her very nature, forever shackled to him.

It all adds up to a story that is less than the sum of its parts, tragically falling short despite having such incredible ingredients. After all, despite everything I’ve said here, I like Lissie and Edward as characters--their voice actors, Nicholas Boulton and Skye Bennett, bring them to life with effortless panache; Ragnar Tørnquist weaved some enchanting dialogue for them--while Graavik itself emerges as a character in its own right. There are beautiful ghosts here, dancing across the mountains limning that fjord. But the story’s the thing, and it does an injustice to both its characters and setting.

***

Dear Esther showed how much was left after it took everything away; Draugen shocks by showing how little is left when you put it all back.

Draugen is considerably more interactive than Esther, with dialogue choices and interactive objects aplenty, as well as ways of engaging with the world that are surprisingly meditative and soothing. There are places Edward can sit to draw in his journal. Although you can run, the game encourages an unhurried pace that rewards attention to its beautiful details. There are pianos to play, bells to ring, cave-ins to outrun, arguments to have, and mental states to breakdown. Yet somehow, so much of it came to feel inadequate.

A game mechanic always suggests something beyond itself. Its very existence points to some distant horizon. If you can pick up an object in a game, it suggests the possibility of picking up other objects, or manipulating them in other ways, and it can be frustrating when that proves impossible. One has to skillfully steer the player’s attention away from what they can’t do, while letting them fully enjoy what they can.

In Draugen you’re meant to take it slow and explore the village. But you’re stymied by doors you can’t interact with, invisible walls in fields and along roads, and more. It’s hard to stop and smell the roses when you’re blocked from even reaching them. The dialogue system has its perks, but it also doesn’t go much further than what one might get in a BioWare game--save for the fact that many options come with clear explanations of what Edward is thinking in relation to each term/concept, which is profoundly more helpful than three word descriptions on a dialogue wheel. The weather changed with Edward’s mood, but so subtly that it wouldn’t have occurred to me to link the two had I not been prompted by the game’s promo material.

And yet there are, as I said, flashes of something more. During particularly heated discussions, Lissie will chide you if you look away from her while she’s talking. It’s a stunning little detail that does so much to involve you in the moment, that implicates you in the scene by refusing the easy logic of video games (‘I can point my head/camera wherever I want and it won’t mean anything’). That bit of feedback makes you accountable to an in-game character--as if she were real. That was a breath of fresh air.

***

But we must return to the issue of mental illness. Is this the worst portrayal of it that I’ve seen in a video game? No, but that’s hardly saying much. By setting up Edward and Lissie to be a fake-out, instead of pitching them to us as a man and an alter, or a man and his imaginary friend, it actually undermines the good that does emerge later in the game.

Contrary to most of the more grotesque portrayals of mental illnesses that involve “hearing voices” or “seeing things,” Lissie and The Entity are not malevolent forces. Edward does not triumph by banishing them, but rather by recognizing both their contingent reality and respecting them as autonomous beings. The former, especially, matches up with how most people like Edward actually live. They know their companions do not exist physically, and instead build life around their insistent existence.

The symmetry with dissociative identity disorder is even more interesting if one reads Lissie and The Entity as alternate identities for Edward that he’s used to process trauma (of which he’s had plenty). Even so, The Entity shades into cliche territory--she berates Edward for pushing everyone else away, intoning that only she and Lissie truly love him. It’s a tired trope of possessiveness that could’ve been quoted from a dozen movies. Lissie, at least, feels more human, the way an actual DID alter might: a person with independent hopes and dreams who can treat her host with profound love. She even emerges as the moral center to the story, trying to focus Edward on the death and desolation around him, enjoining him to solve the mystery so that the people of Graavik can have their stories told. For all her insouciance, she genuinely cares. That is, at least, something relatively compassionate in Draugen’s portrayal of mental illness.

But had the game front loaded with this understanding and let the drama emerge from something in Graavik--rather than using this tragic graveyard of a town as a stage for Edward’s quest for closure--the overall portrayal would have been far stronger. As it is, to service this “surprise! Edward’s craaaaazy!” twist trope, Graavik’s very real tragedies recede into the background, failing even to resolve into coherence by the game’s end.

I realized then, as the epilogue unfolded, that this was a game that actually shied away from its weirdness. Its theater of the mind was halfhearted, reduced only to jump scares of faces appearing in lightning-struck windows. What lay beneath in Edward, in Graavik, wasn’t truly explored. It was as if the game was somewhat ashamed of the territory it staked out, going only so far and then no further. What was left behind was a story that veered dangerously close to ableist cliches. In the end you’re left to speculate about what really happened in Graavik, no clear answers forthcoming; that could have been an artful elision, but as it was it felt like yet another glaring lack in the game. Another missed opportunity.

The end credits thereafter promise, a la James Bond, that “Edward and Lissie Will Return” and--oddly--I was relieved to see that. There’s hope yet for these incredible characters. Hope that they’ll star in a game worthy of them and who they really are--one that won’t turn them into a tortured metaphor or postmodern carnival attraction.

Katherine Cross is a Ph.D student in sociology who researches anti-social behavior online, and a gaming critic whose work has appeared in numerous publications.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)