Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

There's no denying that diving into a world different from our own constitutes one of fiction's greatest attributes.

There's no denying that diving into a world different from our own constitutes one of fiction's greatest attributes.

Between satisfying one's curiosity through free-form exploration of a virtual space or closely following a fictional being's journey through circumstances and surroundings that challenge them, audiences relish the chance to immerse themselves into a realm that promises to evoke all sorts of feelings and themes that make a lasting impression on the participant.

This is especially true with games, where the active nature of the participant encourages them to unearth all that the experience has to offer–all of which is achieved at their own pace.

And if said pace is slow enough, then it becomes likely that players will be treating themselves to a healthy dose of worldbuilding and lore.

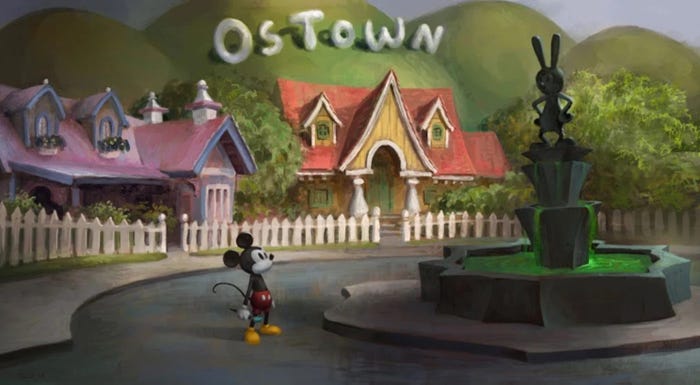

From the simultaneously colorful and bleak world of Epic Mickey (2010) to the solemn rendition of Louisiana in NORCO (2022), virtual worlds bear no shortage of moods and backstories that invite players to learn and understand the set of events and spaces they'll be encountering throughout their journey.

That said, crafting a world is one thing. Conveying it convincingly and without overwhelming players is a whole different beast. Still, both immersion facets mustn't be taken lightly–for developers risk missing out on the opportunity to make audiences care about what surrounds them in-game and the way in which their interactions with NPCs and locations can highlight their authenticity and believability.

----------------

Have a unique premise for contextualizing the action

When it comes to virtual realms, developers must consider the possibility of making their creation as noteworthy as feasible while maintaining a sense of plausibility that respects the player's suspension of disbelief. Whether it's the backstory that details how things came about and persisted in the here-and-now, or the manner in which NPCs interact with their surroundings and one another, worldbuilding boasts sundry layers of narrative depth that can complement one another if developers keep cohesion in mind.

For instance, let's say that we have a world in which magic and technology share an uneasy coexistence with one another—with some species embracing technological progress at all costs and others being ostracized due to their "stubborn" clinging to the magical arts. The result? Multiple societies that vary greatly in terms of beliefs, practices, and architecture—making for a level of variety that drives players to uncover all corners of the proverbial earth and potentially take a side in the magic vs. technology debate.

If that premise sounds familiar, that's because it's the one featured in Troika Games' Arcanum: Of Steamworks and Magick Obscura (2001). Its fantastical rendition of an industrial revolution—which highlights issues of class warfare and unionization that parallel our past—allowed developers to put their unique stamp on the narrative formula for RPGs. The juxtaposition of magic and technology yields an authentic realm that can have players explore and shape every event, location, and NPC they come across. All of this is made feasible by Arcanum's eclectic blend of time-tested motifs and heady themes.

Honorable Mention: The Geneforge series (2001-11). Despite looking like your typical fantasy setting at first glance, Geneforge presents a world with a peculiar hierarchy among its inhabitants and multiple factions that have their own take on the idea of one class having control over another simply because the former crafted the latter out of magical essence.

When one typically thinks of worldbuilding and lore, it's likely that they'll associate those with books, audio recordings, and other collectibles the player can collect while casually exploring the game world. While technically true, it's also true that worldbuilding and lore can be naturally conveyed through the story route that the developers carved for those wishing to just focus on essential activities.

Whether achieved through dialog or the environment itself, lore and worldbuilding can be communicated to players who would otherwise not bother looking for ancillary enlightenment off the beaten narrative path. That said, one should take care to dish out said lore and worldbuilding in small chunks—lest players become overwhelmed by the information they receive and thus unable to retain any tidbits that may help them get a better understanding of the world around them and how they can approach it.

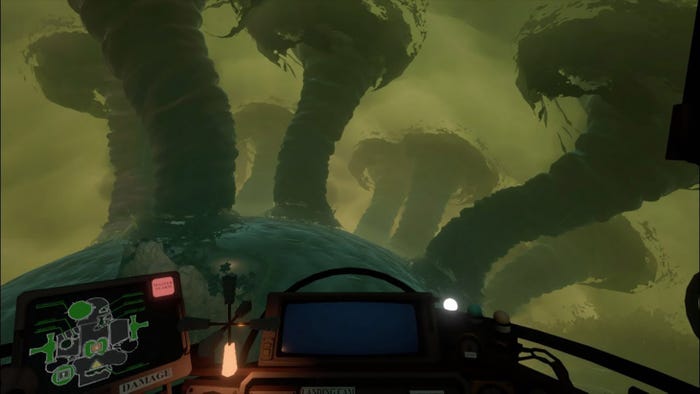

The careful dishing out of lore and worldbuilding along the main path is something that Outer Wilds (2019) nails, chiefly thanks to the exploratory and literal gameplay loop that pushes players to leave no stone unturned while trekking across the final frontier. From prudently wending one's way across obstacles of varying shapes and danger levels, to slowly translating snippets of the Nomai language spread across one's playthrough of the main story, Outer Wilds relays a sense of history and scale that looks daunting before becoming something that can be managed through persistent exploration and an understanding of the in-game world's layout and details.

Honorable Mention: Neverwinter Nights 2: Mask of the Betrayer (2007). While its lore is sizable, the expansion pack only uses worldbuilding details that are relevant to the in-game world's main players and the actions they take. The result is a tale with a solid enough pacing while still providing backstory tidbits that add meaning and depth to the proceedings.

Regardless of which path the player takes while trekking about the virtual land, a game that succeeds at selling said player into its worldbuilding is one that can gradually relay a sense of scale and history—even if that doesn't involve stopping to read or study material that informs the participant on the way their surroundings have been shaped and populated. Given the natural penchant for exploration that one may feel, this effect can be achieved through a good ol' dose of spatial storytelling.

Let's imagine that the game in question tries to sell players into its world via the feeling that they're embarking on a seamless journey that'll take them to locations that vary in their layout and character. Along the way, hints of decaying infrastructure and hostile entities both native and new can clue players in on the state of the world. Not only can this beget stellar gameplay pacing, but it can also result in worldbuilding that the player can easily absorb—irrespective of how quickly they progress through the game.

Such is the storytelling formula that Half-Life 2 (2004) adopts and doubles down on to great effect. Between the uneasy rift among human inhabitants in City 17 (Civil Protection vs. ordinary citizens) and the aftermath of an assault on Ravenholm, the title's surroundings and circumstances manage to strike a balance between letting players proceed at their own pace and inviting them to study the events, locales, and people around them.

Thanks to the relatively seamless way the action plays out (i.e. no cutscenes and only a few loading screens), the player will feel like they've experienced an adventure that left them both thrilled and enlightened on the happenings that they've observed or had a hand in.

Honorable Mention: Death Stranding (2019). The title's focus on covering lots of post-apocalyptic ground means that players will gradually absorb the details and scale of their surroundings while going about their business. Couple that with alien elements that dot the virtual environment, and you've got a recipe for worldbuilding that highlights potent themes of loneliness and connection in a land torn asunder by unfathomable events.

Related to the issue of embedding worldbuilding into main/side stories and via spatial details is the principle of restraint on developers' part. In this case, restraint concerns the importance of resisting the temptation to drop exposition dumps onto players' noggins—lest they fail to get their figurative bearings. This can prove counterproductive in terms of immersion, especially to players who choose to play titles with interesting narrative facets that are unveiled in ideally reasonable quantities at any given time.

Of course, it's one thing to make lore and worldbuilding overwhelming, and another to render those two aspects frustratingly obscure. This is where developers must consider making the act of uncovering more of the world and its backstory part of the gameplay loop. Doing so means that players won't mind being dropped into a world they know little to nothing about, long as the title assures them that all shall be revealed in due time should said players make an effort to hunt down and study objects and characters.

The above description of how players can be expected to unravel the mystery behind their surroundings and the game's past events can be seen in From Software's post-Demon's Souls (2009) output. From the flavor text that accompanies item details, to the cryptic sayings that NPCs utter to the player, the method of worldbuilding and lore-dispensing that the studio specializes in highlights the idea that the player is the one who ought to find information—not the other way around. By trusting their audiences' intelligence and ability to navigate their surroundings, From Software is able to craft worlds that are open to interpretation and organic discovery.

Honorable Mention: Arx Fatalis (2002). The "underground society" premise plays nicely with the idea of venturing through uncharted territory, allowing players to smoothly absorb the worldbuilding and lore that the RPG has to offer. This feeling of uncovering things with little to no handholding is amplified by the oppressive atmosphere and claustrophobic environment.

Logically, worldbuilding that is dryly meted out can only do so much to retain the player's attention in the long term—let alone entice them to fully immerse themselves into the virtual environment. Whether it's through the atmosphere itself or the way in which characters behave toward one another and within their circumstances/surroundings, tone has a palpable impact on how the player interprets the world and provides them with an initial idea of the kind of experience they'll be embarking upon.

On one hand, a game that's serious in mood will register in the player's mind as a journey full of travails and hard truths that may make said player uncomfortable (either due to the action's graphic nature or because of how harshly the truth shatters any preconceived notions borne by the player). On the other hand, a more comical title may entertain audiences and invite them into the humorous goings-on that define the game world—with comedy also acting as an effective tool for luring players into mature subjects and themes.

Fallout 2 (1998) stands as a unique example of a game that proves to be both dark and funny (hence the term "dark humor"). From the sundry vocations that players can adopt in post-apocalyptic America (e.g. prizefighter, sex worker, etc.) to the odd inhabitants encountered in the player's travels (e.g. chess-playing radscorpions, a Bridge Keeper straight out of The Holy Grail, etc.), Fallout 2 never shies away from either its taboo topics or more lighthearted touches.

Ergo, the worldbuilding that stems from the alternate America that predates 2077 is allowed to clearly highlight the contrast between the grim and laugh-it-off factors. Not a usual combo you see in post-apocalyptic media and certainly not one to everyone's taste, but the eccentric lore does lend Fallout 2 that distinct aura of gleeful madness worthy of great satire.

Honorable Mention: Loom (1990). Inspired by Disney classics and imbued with whimsical charm, Brian Moriarty's foray into graphic adventures evokes a feeling of wonderment and wanderlust that compels players to experience Bobbin's journey from start to finish in a state of hopeful optimism. Optimism that's reinforced through striking visuals and musical tracks.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like