Murder school: Crafting Danganronpa to surprise players 2

The series' writer/director Kazutaka Kodaka dives into his approach to game writing and development in this extensive new interview on the award-winning, cult-hit franchise.

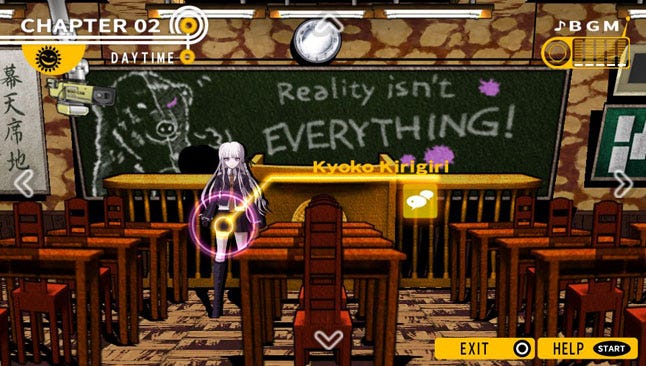

You ought to have heard of Danganronpa by now -- despite it being a series of text-heavy Japanese adventure games only available in the West on the PlayStation Vita. That's because the series has generated a lot of acclaim and interest; Gamasutra is far from the only site to recognize it at the end of 2014.

What's it all about? It's macabre but hilarious; perverse and amoral; strange but relatable. The first game is about a group of high school students, all exceptional, pitted to kill each other in a locked high school -- by a teddy bear mastermind. The second game does the same thing, but this time on a tropical island -- and makes fun of itself for recycling its premise.

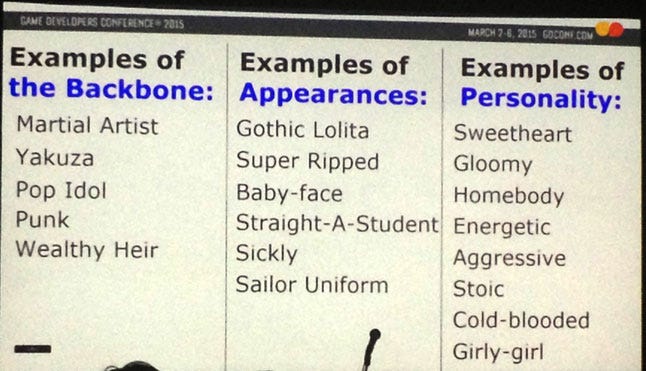

At this year's GDC, the series' writer/director Kazutaka Kodaka gave a talk on his method of creating his brand of memorable stories and characters. He starts with a series of characteristics, and then chooses a sampling that will result in an interesting character -- taking note to mix-and-match intelligently for the biggest emotional impact. The results speak for themselves.

In the following Q&A, conducted during GDC, we get into his method, the characters, and what he wanted to accomplish creatively -- and into the mind of Monokuma, the series' anti-mascot.

NOTE: As it concerns the writing and development of the franchise, this interview contains MAJOR, UNMARKED SPOILERS for the first two Danganronpa games.

It seems that the idea behind Danganronpa is to create something surprising to people. Can you talk about where the idea first came from, and how you approached it?

Kazutaka Kodaka: I guess you could say one of the representative things of Japanese mystery fiction is that it's got a lot of twists, turns, and surprises. I'm actually a pretty big fan of mystery fiction. I figured, well, what if you were going to do a mystery-style game -- a mystery as a game, instead of a novel? That would be Danganronpa.

In my mind, American "mystery" is more like suspenseful drama, whereas I feel like in Japan, that genre means surprising your reader.

In the first game, you killed off the heroine very quickly -- in the first case. And it sort of tells the player, "this is not going to go to your expectations." Can you talk about that decision, and why it was important?

KK: For that... At that time, Danganronpa was new. It was the first in the series, and I felt there had to be something that would really grab players so they'd want to play and keep playing. So what I thought would be one of the best ways was to have the Sayaka Maizono character meet her untimely death.

And not just that, but she also tried to frame the hero for a crime -- that's the more twisted part.

KK: Going off what you just said, yeah, you're right. That's a really good point. Part of it was to provide a vehicle for [protagonist Makoto] Naegi's growth. What that kind of means is that Sayaka herself obviously had her own feelings, and maybe she did it to send him a message, or leave him a message. Maybe she did it because she wanted to live, obviously. Maybe she did it for whatever reason.

The point of the matter is that what that ended up doing is hastening Naegi's growth as a character, through this idea. The same thing with [her killer], Leon Kuwata. Naegi ends up having to shoulder the deaths of these two, and go on with his life, as it were. That ended up being a really good vehicle for me to have that character move forward and act.

"A part of that is just that I want to have a good shock and scare in there. By the same token, if you only do that, what you end up with is a wasted chance."

Would you say that when you create a situation in the game, it's not enough to have it be entertaining, but it also has to move the plot forward, or the characters forward?

KK: Yeah. A part of that is just that I want to have a good shock and scare in there. By the same token, if you only do that, what you end up with is a wasted chance.

So I try as much as possible to make sure that the surprise elements and surprise scenes are also connected to the characters, and allow the plot to move forward. I definitely put thought into it to make sure those surprises have an outcome and have a connection to the plot itself, and the characters.

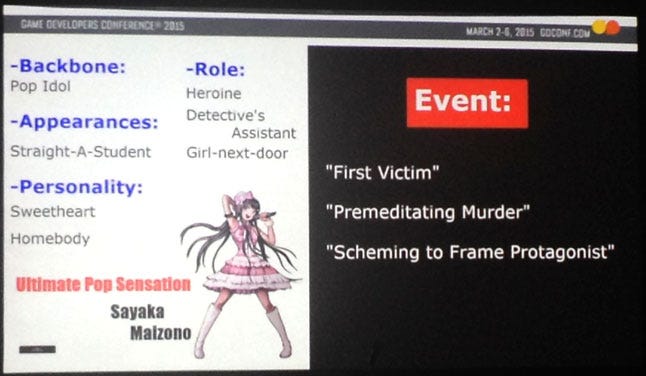

Kodaka's slide on Sayaka Maizono from GDC. Here he shares her character traits and the events that shape the direction the story around her takes -- note the contrast.

To give you an actual example of how I do this, let's go back to Sayaka's case. Like you said, it's surprising because she's the culprit. In a way, Naegi, the main character, is betrayed by her. She presents herself one way, and she ends up doing this horrible thing.

And so, if she was the one who was simply murdered, the player would probably go with Naegi, and feel sympathy for her. And the only thing you would feel would be sympathy for her. There would be no real growth; there's no way to move forward from that. It's just, "Oh, a sad thing."

However, by making her actually the culprit, suddenly there's this conflict within Naegi. Of course, he feels bad for her, because he cared for her. But at the same time, she did something wrong. So the player's forced to approach it the same way Naegi is, with this feeling of, "Well, on the one hand there's this, and on the other hand there's this." He has to deal with conflicting emotions in both of these things to move forward. And the player does, too. And that's the way I try to write all of that.

I want to ask you about suspension of disbelief. There are so many elements of the stories of the two games that are so far out there, yet as a player, you can go with them. How do you keep the players inside the story?

KK: I think that my approach is probably similar to a typical science fiction approach -- no matter how strange or outlandish the setting might get, the constant that you have to have is characters that display real and genuine emotion that someone can relate to.

By doing so, the player will accept pretty much anything that's thrown at them in terms of the setting. Because the characters themselves are real, and genuine, and have real emotion, that allows the player to enter into the game, and feel comfortable with it.

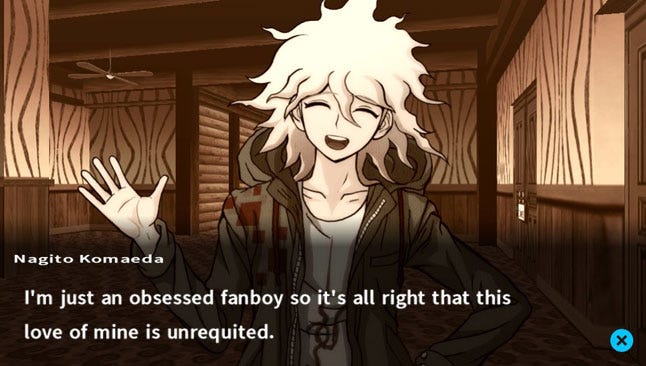

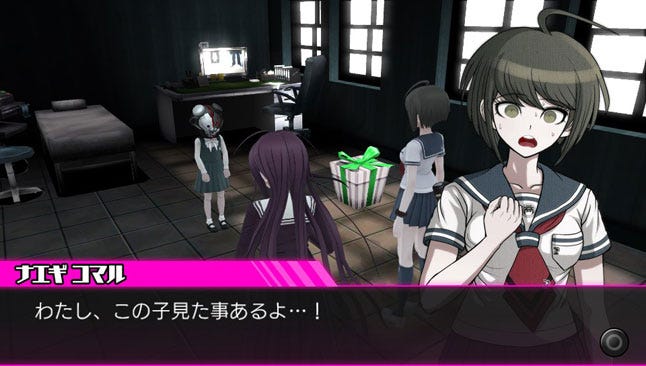

But then, some of the characters are hard to relate to. How do you write a character like Nagito Komaeda and make him work?

KK: You're right. He is a really crazy character, and that's by design. The way I approach the characters is to start with the category: For example, the genki girl, as it were, or the stoic straight-man kinda thing. But at the same time, those are just a vehicle to me to get a character. Because that's my approach -- to have this category in mind -- the approach for Komaeda was actually "uncategorizable." My inspiration for that was actually Batman and Joker.

What I really wanted to do with that character, myself, was to have the player-base divided: "What the hell does this guy think he's doing?" and then, on the other hand, "Well, I can kinda relate to this guy. I can kinda get behind what he's doing." And that was my hope and desire, to have people approach the character.

The slide from Kodaka's presentation where he discusses the "category" framework, with some Danganronpa-specific examples. These are to be mixed and matched to create characters, with the result shared above (Sayaka Maizono).

The slide from Kodaka's presentation where he discusses the "category" framework, with some Danganronpa-specific examples. These are to be mixed and matched to create characters, with the result shared above (Sayaka Maizono).

And then, when he dies, you don't know whether to believe it or not. And I think that was really important.

KK: In regards to that directly, when I was giving direction to the voice actor, the voice actor was like, "I have no clue what this character is thinking! So it's really hard for me to do this scene." Giving direction for this character was very, very challenging.

Isn't the voice actor for that character Megumi Ogata? [Ed. note: Ogata is best known for playing protagonist Shinji Ikari in Neon Genesis Evangelion.]

KK: Yes. So you know, the character -- I don't know if it's necessarily an anagram in English, but if you move the characters [in "Nagito Komaeda"] around, it's "Naegi Makoto da." [Ed. note: meaning "It's Makoto Naegi," who is the protagonist of the original game.]

The main reason was to get players questioning, "Wait a minute! Is this the same guy wearing different clothes?" kinda thing. In order to that, Megumi Ogata was the go-to person for that. That's why we chose her.

So, it was planned. About three months before the game came out in Japan, we announced the voice actors and stuff like that. People were speculating on the web. They were like, "Oh, this is an anagram. It's the same guy!" And in the development room we were all laughing because, "Of course. That's what we wanted to do to you guys!"

One thing the game does, and it's quite common in modern media, both Japanese and American, is that it makes fun of itself. It points to itself and nudges you.

KK: Metafiction? It's just that it's an interesting thing to do. It's interesting to have the self-referential meta-thing going on.

For me, what I think is particularly interesting about it is that as a player is playing a game, obviously they're getting involved, and they're entering it. And the moment you throw a fourth wall thing, or a meta-joke, they're instantly pulled out of that. So it creates this sense of unease, and I really like how it does that to the player.

You also use really ridiculous moments, sometimes. One of them is when Nekomaru turns into a robot. What's the point of using something so ridiculous?

KK: For me, my writing style is actually that I write everything out as a list of points I want to hit -- everything I want to do within the story. Sometimes those are really serious things, and sometimes those are very comedic things.

So, in Nekomaru's case in particular, I had a note: "I want a robot to be in here." I thought if the guy was a robot from the beginning, it wouldn't be accepted very well, and it waould just come across as stupid. But I wanted to do it somehow, and that's the form it ended up taking.

I also feel that I personally have a short attention span, and I want to put a little comedy in there to break up the monotonous seriousness.

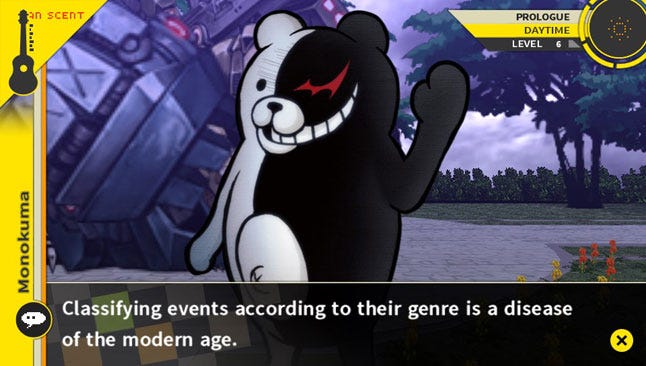

And then there's Monokuma, right? First of all, most Japanese things need to have a mascot, right? Monokuma is a twisted mascot.

KK: Originally, Monokuma was this very "black and white" character -- sometimes it would say crazy things, sometimes it would say serious things, funny things, and everything like that.

But what it actually evolved into, as I was writing the character, is my own personal feelings about things -- the things that I wanted to say. Every character has a fact-sheet about them, but Monokuma has none, because it's kind of my own, personal inner thoughts and inner ways of thinking.

If I had originally gone with the original idea of this "black and white" character, it could have been more of a mascot, in a way. But what it turned out to be is more of an author-expression vehicle, where I could just talk about what I wanted to say.

The author always expresses him or herself into a story, but not so directly. How much can you put yourself into Monokuma's words?

KK: It's pretty unfiltered. Part of it is that when I write Monokuma, I'm imagining what the player would say. It's to figure what they're thinking and then say, "I did that because I wanted to! This is the way it's gonna be -- I wrote the game!" That's the feeling behind it.

A lot of the time, Monokuma's lines are looking at it from the perspective of, "What are people going to say right now, when they're playing it? What would the characters say if they were looking outside of themselves?" And then, turning that on its head and saying, as the writer, "This is really want I want to do." So it is very much so my comments on what's happening, and comments directed to the player.

Why did you choose the theme of despair at the outset? That's an unusual theme for entertainment.

"As I began to write from that idea, that despair theme grew and took over everything."

KK: Well, originally, the Japanese subtitle of the game, literally translated it would be "The High School of Despair and the Students of Hope." So the original idea was these students are exceptional in something. As they were, they had very bright futures -- lots of hope for the future, as it were. And then they're placed in a very desperate, despairing situation.

As I began to write from that idea, that despair theme grew and took over everything -- and then it became the main theme of the game, even though that wasn't necessarily the beginning theme.

How do you avoid putting too many moe characters in the game? So many Japanese games are filled with moe characters. How do you stop them from making you put moe characters in the game?

KK: I don't really care for the moe thing to begin with. Obviously, a lot of visual novel games are based on beautiful girls -- that's a genre, beautiful girls and their little situations, and whatnot. I don't really care for that. I don't know how to write a game like that. Even if I tried, I probably couldn't. I just don't really want to.

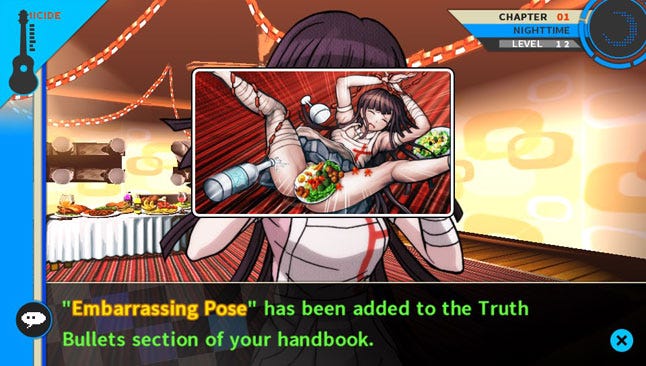

Every time there's a girl who could be like that -- like Sayaka Maizono -- she gets taken away, pretty fast.

KK: Yeah, in a way, that's true.

I really like to poke fun at current trends. In the fan-service, too. Tsumiki has a scene where she's totally splayed, and that's poking fun at that whole thing. There are characters like Maizono-san from the first game, poking fun at conventional, cute girls. Monokuma itself is poking fun at the convention of mascots.

What I think I would like to do right now, is social games are really popular in Japan. I'd like to poke fun at social games as well.

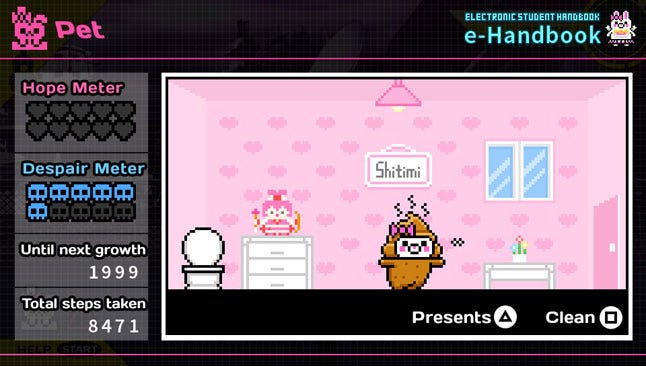

There's a virtual pet in the second game, and I didn't clean it, and I ended up with a shit pet. Was that your idea?

KK: That also, in the same way, was making fun of the Tamagotchi boom that happened so long ago. I'm the kind of person where if I see something boom, I want to make fun of it. For example, when I see people playing soccer, it's like, "Why not use your hands, guys?" That's the kind of person I am.

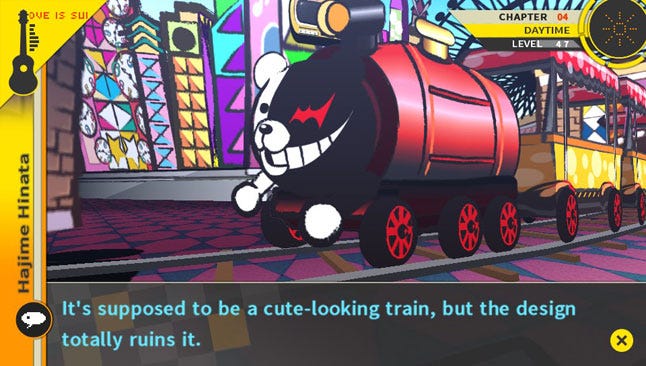

The latest Danganronpa game: Ultra Despair Girls, which came out in Japan last year and is due to be released in the West this fall.

The latest Danganronpa game: Ultra Despair Girls, which came out in Japan last year and is due to be released in the West this fall.

How strictly are the events in the game planned, when does writing begin, and how do you handle that?

KK: Probably the best way to answer this question is to give you an example of how we developed Ultra Despair Girls. Traditionally, you'd have the level designers make a level, game designers make a game, consult with the scenario writer, and see how we could coordinate those together.

It's the opposite for me. I write the scenario and then I kind of tell them, "They're going to go to a place like this, so we should do something like this. This is gonna happen, so we're going to make the game play like this." That's how it comes to be. It was the same way with Danganronpa 1 and 2. I start with the scenario and write the scenario first, and from there, I pick out how the game is going to go based on the scenario and script.

How complete is your scenario when you write it at first? Are we talking about a broad outline, or the whole script?

KK: It's a very fluid process -- perhaps too fluid. The ideal scenario would be to write the whole scenario first, offer it to the team, and go from there. But what usually ends up happening is that I'll reach a certain level, then pass it over, and then they'll start making something, and then I'll go, "Ooh, actually, could you change that, please? Let's go with this instead." So a lot of things are in flux as I'm writing.

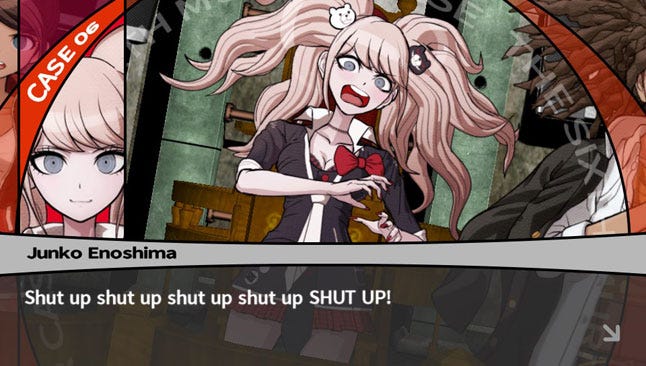

To change gears: Why Junko? Can you tell me about where that character came from, and why she is the way she is?

"Playing with people's expectations is what I want to do with the series."

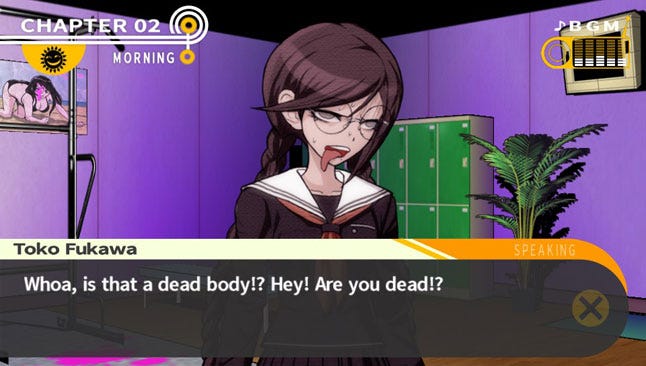

KK: Junko, as you know, has multiple personalities. When I was writing the game, I already had the character Toko Fukawa, Genocide Jack, who already had that. The easy answer would have been to make that character the last boss, as it were -- the final enemy, the mastermind.

But playing with people's expectations is what I want to do with the series. So I said, "No, no, no. Let's one-up this. Let's go to the next level with this multiple personalities thing -- and really go crazy with this."

In addition to that, I've noticed that in a lot of media nowadays, the final enemy, the mastermind, the bad guy always has something -- some trauma, something in their past, some "I do this because this is my system of justice and my beliefs, and I have to fight for it."

No. I'm done with that. I wanted to make someone evil for the sake of being evil, who only wanted pure despair. No redeeming qualities, evil for the sake of evil. That's kind of where that character came from.

Why is she a model?

KK: It's a very different place than the character's motivation. I don't think of her as "a model," I think of her more as "cute." I like the idea that the cutest one is the first one to go -- but in a strange twist of fate, in the end, she's actually the mastermind.

Another thing I really wanted to do was to create a really, really cute character that was evil. Also to have this idea that absolute evil is still something that desirable, or overwhelming. And despite of how bad it is, because it's so powerful, and so absolute, you're still drawn toward it. And one way I thought to do that was to make a really, really cute character -- visually incredibly appealing.

The reaction to that was what I wanted, because she's an incredibly popular character -- especially so in Japan. People really love the character.

Do you think that characters like Junko, and the evil she has in her, are real?

KK: I don't think so. No, I don't think people like that exist, but by the same token, if to create a character like that, I'd made some ripped muscle-dude, there's really nothing surprising or interesting about that. On the other hand, having this girl who's slender, who maybe looks weak on the outside, but in actuality has this appeal about her, this is for me personally very interesting and appealing, and an idea I really wanted to explore.

I think the fact that she is the way she is, lends some believability to the fact that she'd have the charisma to push something like this forward, actually.

KK: Thanks. In terms of cosplaying, actually, most cosplayers want to play as her. Just looking at the character's lines by themselves, it's like, "Wow. That's a horrible thing to say." But even still, people want to cosplay as her.

That's an awesome example of what Danganronpa is all about: Hope and despair, all wrapped into one. She's a good symbol for the series.

You must have been asked before if you're surprised at the series' popularity, so I don't want to ask that question. But I want to ask about your reaction to the popularity in both the West and Japan, and why you think it's popular.

"It's the game that I like, that I wanted to make, that I wanted to play."

KK: First of all, I want to say that the company is small. We don't have a huge budget. I like to think that the way we make games is kind of indie-style. So when we created the game, it was like, "Convention be damned. We're going to make the game we want to make." In light of that, I feel that the company is very rare and very special, and the game is too.

Because of that, when we made the game, because we had this indie spirit, we didn't have this "let's create a game that we think is going to sell." There are lots of games out there, if you look at it, that are essentially made to sell -- and they're good games.

But on the other hand, Danganronpa is not. It's a game that I think is interesting. It's the game that I like, that I wanted to make, that I wanted to play. And I want to believe that this feeling, that creative source, is what resonated with people, and why people like the game.

The Danganronpa series' pop art visuals. The style is more pronounced in the first game.

The Danganronpa series' pop art visuals. The style is more pronounced in the first game.

For more on that choice, read our prior interview with producer Yoshinori Terasawa, and associate producer Yusuke Katagata.

I don't know if you're aware, but people dug up a lot of old material on the game from when it was announced, and it was a lot more normal. Can you talk about, in light of what you just said, why it changed?

KK: Like you just said, that game would have been a normal game. It would have fallen into that conventional horror game category, and consequently, it would have ended up having to compete with other games like it. I don't feel that it could have, as it was.

So what we did to combat that, and move forward to the game, was to add these pop art elements. That's what caused Danganronpa to be what it was, which then put it in its own category, so that it didn't have to fight with anything else but itself, and only be itself.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)