Maximizing Gameplay by Satisficing

Maximizers tend to enjoy structured games over unstructured games, whereas satisficers have a capacity for enjoying both, and will generally have a better time of playing unstructured games than maximizers.

Why do some people enjoy certain games over others? Is it because of how “well” the game is made by the developers? This no doubt has an effect on the overall rating and public opinion of the game, but that is definitely not all that determines whether an individual person will like the game. Things such as experiences, memories, personal identity, and a plethora of other factors may affect an individual’s opinion of a game. I will not attempt to address every single factor that can go into making a person like a game, as that may be near impossible without hundreds of pages. Instead, I will attempt to identify one major factor that can have a significant effect on one’s experience when playing games: maximizers tend to enjoy structured games over unstructured games, whereas satisficers have a capacity for enjoying both, and will generally have a better time of playing unstructured games than maximizers.

To make sense of what I just said, I must define two terms: maximizers and satisficers. I came across these terms in a book called The Paradox of Choice by Barry Schwartz. “If you seek and accept only the best, you are a maximizer…Maximizers need be assured that every purchase or decision was the best that could be made” (Schwartz 77). As examples in the context of gaming, a “maximizer” might only move on to the next level in Angry Birds after getting 3 stars on every previous level, or they may never leave a dungeon in Skyrim until they are convinced that they have picked up every single gold coin or item of value. As also described by Schwartz, “The alternative to maximizing is to be a satisficer. To satisfice is to settle for something that is good enough and not worry about the possibility that there might be something better” (Schwartz 78). The word “satisficer” is an amalgamation of the two words “satisfy” and “suffice.” In gaming, a satisficer may go through the levels of Angry Birds, only caring about getting to the next level instead of spending their time finding the optimal way to take down the green pigs, or they might go through Skyrim only caring about the major treasure at the end of each dungeon. Of course, there is a spectrum between the two since it is nearly impossible to solely classify a person as a 100% maximizer or a 100% satisficer. In fact, some people may be more of a maximizer in some situations and more of a satisficer in others. Even so, many people may identify themselves as generally a maximizer or generally a satisficer when it comes to gaming. Which one are you? Just think back to games you have spent a lot of time playing. Did you take extra time to ensure everything was done perfectly and completely? Or did you move on to the next part of the game even if you did not completely explore or finish the first part?

While I will use “maximizer” and “satisficer” to define subsets of players, I will also attempt to classify games as being “structured” or “unstructured.” I am creating these classifications based on the terms “ludus” which means “controlled play” and “paidia” which means “spontaneous play” (Vader, “Gaming Conceptz”). As an alternative to these definitions, in this paper I will refer to games that generally fall under the realm of ludus as “structured” games, and those that fall under the realm of paidia as “unstructured” games. Even though there is also a spectrum here where most games will not fall into exclusively one category or the other, my classifications will be based on the typical gameplay for each game.

To revisit my thesis, this paper will attempt to construct a relationship between whether a player is a maximizer or satisficer, and whether they tend to enjoy structured or unstructured games. To do this, I will present a few examples of games that are structured or unstructured, and discuss why maximizers or satisficers might enjoy them more. The games I discuss are not a random sample of all games. Instead, I will mostly discuss games that I have played extensively, so as to avoid incorrectly classifying and analyzing them. It should also be noted that the analysis of the games I will discuss are my opinions and by no means absolute, although I will try to back up my classifications with academic sources and logic.

Why would maximizers enjoy structured games over unstructured games? It stems from the number of choices present in structured versus unstructured games. Take Skyrim, for example. While certain parts of Skyrim are structured, such as the specific spells or weapons that do a specific amount of damage to enemies based on their armor and the optional main questline, the game as whole is very unstructured since the player can do pretty much whatever they want, and there is so much to do. Kirk Hamilton, an editor-at-large for the video game website “Kotaku,” published an article entitled “Skyrim is the Pinnacle of Short Attention Span Gaming.” Throughout this article he essentially explains that he did not have much direction while playing Skyrim, that “These days, I mostly just wander around. And it’s great!” (Hamilton, “Kotaku”). Hamilton strikes me as a satisficer based on the way he talked about Skyrim, and it’s no wonder he enjoys it! Skyrim boasts an enormously vast world with over 340 major  locations. With such a vast world, how can one help but enjoy exploring the variety of experiences it has to offer? I’ll tell you how: the number of choices is unimaginable while playing Skyrim. First of all, one must decide which of the 340+ locations to visit (which may be guided by quests, although it is really easy to rack up a ton of quests and difficult to choose which one to pursue), and once they get to a location, they are presented with more choices. These may include whether to spend time picking each flower around the entrance to a location or on the path to get there, or which items to pick up in a cave so as not to exceed their carrying capacity while maximizing the value they get from the items they hold. A satisficer would be content to forego many things in Skyrim and simply bypass the 10th set of steel boots they come across in a dungeon or the 15 different iron ore veins they could take time to mine in the next cave they explore. A maximizer would likely be compelled to have an entirely different kind of experience. They might pick up everything they see thinking that they can sell or use it later. This typically results in a large bag of junk that never gets used or is not worth the time it took to get. A maximizer might explore 1 location in 3 hours while a satisficer may visit 5 locations in the same amount of time. I am not saying that maximizers are not able to enjoy playing Skyrim, but their immense attention to detail could detract from their overall gameplay experience by keeping them from enjoying the vast open world. They may just become stressed with all the choices presented to them since they want to exploit every single one.

locations. With such a vast world, how can one help but enjoy exploring the variety of experiences it has to offer? I’ll tell you how: the number of choices is unimaginable while playing Skyrim. First of all, one must decide which of the 340+ locations to visit (which may be guided by quests, although it is really easy to rack up a ton of quests and difficult to choose which one to pursue), and once they get to a location, they are presented with more choices. These may include whether to spend time picking each flower around the entrance to a location or on the path to get there, or which items to pick up in a cave so as not to exceed their carrying capacity while maximizing the value they get from the items they hold. A satisficer would be content to forego many things in Skyrim and simply bypass the 10th set of steel boots they come across in a dungeon or the 15 different iron ore veins they could take time to mine in the next cave they explore. A maximizer would likely be compelled to have an entirely different kind of experience. They might pick up everything they see thinking that they can sell or use it later. This typically results in a large bag of junk that never gets used or is not worth the time it took to get. A maximizer might explore 1 location in 3 hours while a satisficer may visit 5 locations in the same amount of time. I am not saying that maximizers are not able to enjoy playing Skyrim, but their immense attention to detail could detract from their overall gameplay experience by keeping them from enjoying the vast open world. They may just become stressed with all the choices presented to them since they want to exploit every single one.

Let’s look at a few games on the other end of the spectrum. Super Mario Bros. is a highly structured game with a definite goal: to move from left to right on the screen and get to the flag, and then do the same thing in the next world. I am only addressing the side-scrolling classic Mario style games here to be clear. Sure, there is some variation with entering pipes to bonus levels or climbing vines to the clouds, but that is just to provide some complexity and excitement to an otherwise linear game. The number of choices in Mario games is miniscule compared to a game like Skyrim. Therefore, satisficers will be satisfied with going straight through the levels and getting to the end, and maximizers will be satisfied with spending a bit of extra time searching for secrets throughout the level, but ultimately still reaching the end within the set time limit.

Let’s look at a few games on the other end of the spectrum. Super Mario Bros. is a highly structured game with a definite goal: to move from left to right on the screen and get to the flag, and then do the same thing in the next world. I am only addressing the side-scrolling classic Mario style games here to be clear. Sure, there is some variation with entering pipes to bonus levels or climbing vines to the clouds, but that is just to provide some complexity and excitement to an otherwise linear game. The number of choices in Mario games is miniscule compared to a game like Skyrim. Therefore, satisficers will be satisfied with going straight through the levels and getting to the end, and maximizers will be satisfied with spending a bit of extra time searching for secrets throughout the level, but ultimately still reaching the end within the set time limit.

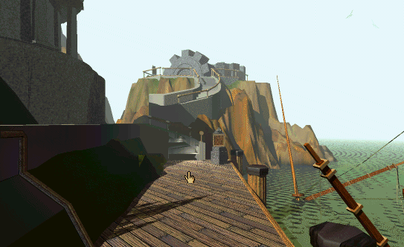

Another slightly more modern example of a structured game is Myst. Myst is a puzzle game (a 5 game series, actually) where the player controls a character in first person and clicks to move around a map. There are hidden clues scattered throughout each map which the player must decipher to solve puzzles and progress in the game. On the surface this may seem like an unenjoyable game for maximizers, since they might spend a lot of time scouring the map for every little detail they can find. However, Myst is divided into a series of smaller worlds and maps that make each portion manageable and provide the user with a clear goal to progress to the next map. Solving the puzzles requires things such as finding single sheets of paper on the ground and reading them for a clue to operating a device that will open a door. Good attention to details in each section is required to successfully play the Myst games. According to an article by Supriya Chaudhury about marketing to maximizers and satisficers, “Satisficers might limit their research to the top two or three search results from a keyword query or category search at an online retailer. They are much less likely than maximizers to explore search results past the top few” (Chaudhury, “Clavis Insight”). Based on Chaudhury’s article, in Myst satisficers may just want to explore a few interesting locations and move on even though they would have to revisit locations and take time at each part to solve the puzzles. In this sense, Myst may actually not be great for satisficers because it requires so much attention to detail and determination to examine every possible location on the map. Conversely, for maximizers “the consideration process is long and deep exploration is desired. Maximizers will read ‘below’ the fold, analyze the product information you offer, and scrutinize product ratings and reviews” (Chaudhury, “Clavis Insight”). Judging from this section of the article, maximizers would appreciate all of the details in Myst and have a good time analyzing them for valuable information. Therefore, Myst is a structured game that might be more enjoyable for maximizers than satisficers.

Another slightly more modern example of a structured game is Myst. Myst is a puzzle game (a 5 game series, actually) where the player controls a character in first person and clicks to move around a map. There are hidden clues scattered throughout each map which the player must decipher to solve puzzles and progress in the game. On the surface this may seem like an unenjoyable game for maximizers, since they might spend a lot of time scouring the map for every little detail they can find. However, Myst is divided into a series of smaller worlds and maps that make each portion manageable and provide the user with a clear goal to progress to the next map. Solving the puzzles requires things such as finding single sheets of paper on the ground and reading them for a clue to operating a device that will open a door. Good attention to details in each section is required to successfully play the Myst games. According to an article by Supriya Chaudhury about marketing to maximizers and satisficers, “Satisficers might limit their research to the top two or three search results from a keyword query or category search at an online retailer. They are much less likely than maximizers to explore search results past the top few” (Chaudhury, “Clavis Insight”). Based on Chaudhury’s article, in Myst satisficers may just want to explore a few interesting locations and move on even though they would have to revisit locations and take time at each part to solve the puzzles. In this sense, Myst may actually not be great for satisficers because it requires so much attention to detail and determination to examine every possible location on the map. Conversely, for maximizers “the consideration process is long and deep exploration is desired. Maximizers will read ‘below’ the fold, analyze the product information you offer, and scrutinize product ratings and reviews” (Chaudhury, “Clavis Insight”). Judging from this section of the article, maximizers would appreciate all of the details in Myst and have a good time analyzing them for valuable information. Therefore, Myst is a structured game that might be more enjoyable for maximizers than satisficers.

The sandbox game, Minecraft, introduces an interesting dilemma that affects how I classify it: the game has no set goals. If one only considers that the game does not guide the player in any way, it may be considered an unstructured game. However, the game also allows for a number of personal goals that players can develop on their own, which adds a degree of structure. For example, players can enter “survival mode,” a game mode where players start with nothing and must get all resources from the wild. A personal goal in this mode might be to collect resources and create a “base”, or home, at an interesting location using only blocks that the player gets by themselves. This could pose a problem for maximizers who tend to “pursue the goal to optimize every decision. If many different options are available, this goal is difficult to fulfil. The failure to achieve goals promotes dissatisfaction, even if their choices are reasonable” (Moss, “Sico Tests”). Due to the unlimited locations in Minecraft (worlds generate infinitely), it is impossible for one to find the “best” location for their base (prettiest, most interesting,  etc.). Therefore, maximizers will likely never fulfil the part of their goal to create a base at an interesting location. The infinite number of resources (wood, coal, various ores, etc.) available in Minecraft may also inhibit the progress of maximizers towards their goal because they might get stuck on the “collect resources,” never feeling like they collected enough resources. Based on the Moss article cited above, a playstyle such as this would likely promote dissatisfaction for maximizers. Alternatively, “adding options doesn’t necessarily add much work for the satisficer, because the satisficer feels no compulsion to check out all the possibilities before deciding” (Schwartz 93). With this mindset, satisficers would not spend a ridiculous amount of time finding the perfect base location. They would also be satisfied with just collecting enough resources for whatever task is at hand rather than trying to prioritize their excursion and fill their inventory with the maximum number of resources that can fit. This is not the only way to play Minecraft, but it is a common example of a partly structured way to play an overall unstructured game.

etc.). Therefore, maximizers will likely never fulfil the part of their goal to create a base at an interesting location. The infinite number of resources (wood, coal, various ores, etc.) available in Minecraft may also inhibit the progress of maximizers towards their goal because they might get stuck on the “collect resources,” never feeling like they collected enough resources. Based on the Moss article cited above, a playstyle such as this would likely promote dissatisfaction for maximizers. Alternatively, “adding options doesn’t necessarily add much work for the satisficer, because the satisficer feels no compulsion to check out all the possibilities before deciding” (Schwartz 93). With this mindset, satisficers would not spend a ridiculous amount of time finding the perfect base location. They would also be satisfied with just collecting enough resources for whatever task is at hand rather than trying to prioritize their excursion and fill their inventory with the maximum number of resources that can fit. This is not the only way to play Minecraft, but it is a common example of a partly structured way to play an overall unstructured game.

Which mindset should one choose in order to get the most out of their gaming experience? It depends. For generally unstructured games such as Skyrim or Minecraft, satisficers may have a better experience than maximizers due to the abundance of choices. For generally structured games such as Super Mario Bros. or Myst, maximizers may have an equally good or better experience than satisficers due to the lack of choices. The common variable here is the amount of choice present in a game. More choices cause maximizers to feel as if they cannot find the best choice, whereas satisficers may just meet their goal faster when presented with more choices. Having fewer choices is likely preferable for maximizers, but will not affect satisficers much since they will still likely meet their goals. Due to this, satisficers will more deeply enjoy a wider variety of games than maximizers. Although, there are exceptions such as Myst which may be more preferable for maximizers. Now, let me ask you again, which one are you?

Bibliography

Chaudhury, Supriya. "Maximizers vs Satisficers: Optimizing Online Product Content."

Clavis Insight. N.p., 11 May 2016. Web. 30 Nov. 2016.

Hamilton, Kirk. "Skyrim Is the Pinnacle of Short Attention Span Gaming." Kotaku. N.p.,

22 Nov. 2011. Web. 30 Nov. 2016.

Moss, Simon. “Maximizing versus Satisficing.” Maximizing versus Satisficing /

Smoss2 – Sicotests. N.n., 6 June 2016. Web. 30 Nov. 2016.

Schwartz, Barry. The Paradox of Choice. New York: Harper Collins, 2004. Print.

Vader, Vince. “Paidia & Ludus.” Gaming Conceptz. N.p., 5 Dec 2012. Web. 30 Nov. 2016.

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like