Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In the heady, early days of the FPS, new developers were trying new things -- and the story of Immercenary, an all but forgotten 3DO exclusive published by Electronic Arts, is one of a new studio, new ideas, and a direction different from the genre's current status quo.

September 19, 2012

Author: by John Szczepaniak

With the recent 7DFPS game jam, indies attempted to release the first person shooter from its current creative stagnation. But it wasn't always such a conservative genre; its early days, in the 1990s, were a time of wild experimentation. To remind us of that, it's worth examining the genre's early titles -- ones that went down roads not traveled today.

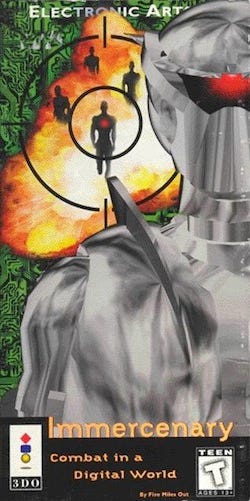

Released in 1995 for the 3DO, Immercenary was a faux-MMO shooter set in a decidedly 1990s cyber-future. It was released when the internet had just begun to enter the popular consciousness, the 3DO was the most powerful console on the market, Doom was only two years old, and games like Quake, Half-Life, and Ultima Online were still several years away.

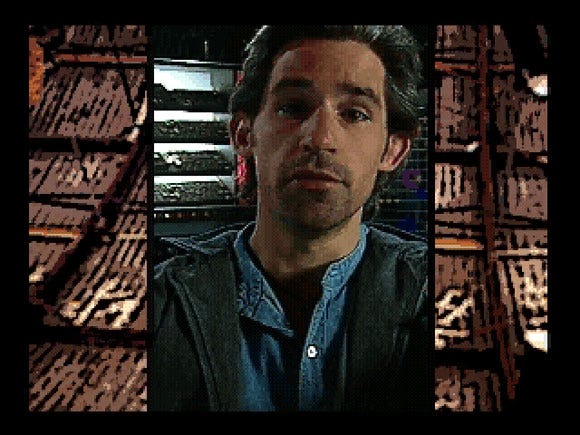

Though ambitious, Immercenary [YouTube gameplay video] was the first project for newly-formed developer Five Miles Out. Co-founder Chris Stashuk, a graphic design graduate, started out as art director for the Martin & Martin agency, shifting its work environment to computers.

"In 1992, the potential of computer graphics was really coming into fruition. I think it was my eagerness to create in a digital environment that prepared me for Five Miles Out," says Stashuk.

He was invited to start the company by co-founder JD Robinson. "I was at the same university JD attended, and worked on some collaboration projects. He approached me in 1993 about [being] lead artist with the new company he was forming.

"So I started training in 3D modeling and animation, working in 3D Studio Max. Other programmers and videographers came on board, and we started working with the theme for Perfect, which Electronic Arts renamed Immercenary."

Also involved was Marla Johnson-Norris, a veteran of television production, who had a small video production company at the time.

Also involved was Marla Johnson-Norris, a veteran of television production, who had a small video production company at the time.

She explains how EA laid the groundwork for Immercenary: "JD, a good friend, had worked with Ozark Softscape legend Danielle Bunten, creator of M.U.L.E. When EA producer Jim Simmons asked JD if he would consider developing a design document for a game, for a new platform that incorporated video in a way previous platforms had been unable, JD put together a team that included me to work on the document."

It's worth considering that when development began, the 3DO wasn't out yet. Console gamers were still playing the Super Nintendo and Sega Mega Drive/Genesis, and the landmark PC FPS, Doom, wouldn't arrive until the end of 1993. Even the CD-ROM was new.

The prospect of working on new hardware -- which arrived before the PlayStation made 3D graphics and CD-ROM mainstream parts of console gaming -- was exciting for Stashuk and the team. "With the 3DO platform on the brink of release, it was decided that we'd apply all of our programming development research towards 3DO as the release platform, which at the time expressed huge potential," he says.

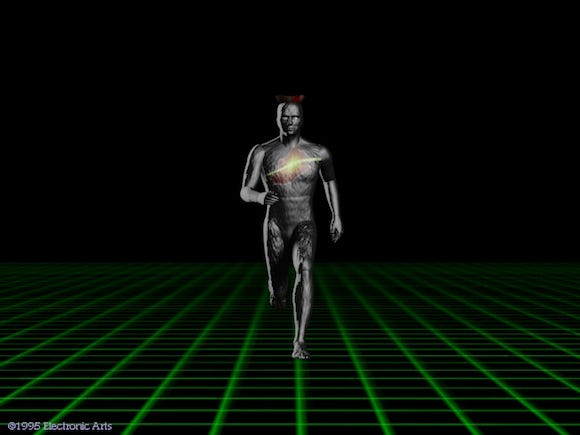

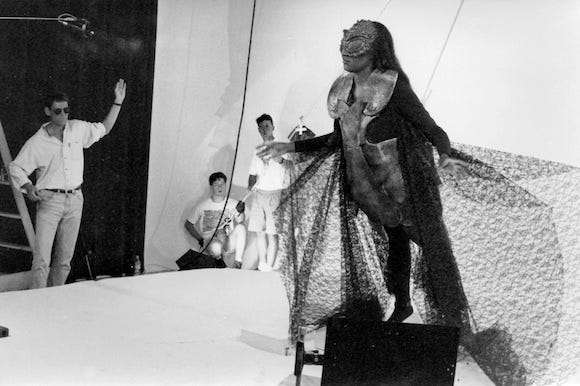

Current FPS development is dictated by advancing hardware, and so it also was in the early 1990s for Immercenary. Johnson-Norris describes some of the technicalities: "We put together a plan to show off the capabilities of the platform, EA accepted it, and we were funded to develop it. We hired the staff and got to work. My focus was the machine's capability to deliver video or film quickly.

"We shot video and film sequences of the characters and tested the quality of the imagery in the game environment. We had a film specialist with EA come out and work with us. We ended up going with high quality video instead of film -- it actually delivered an equal quality for a lower cost."

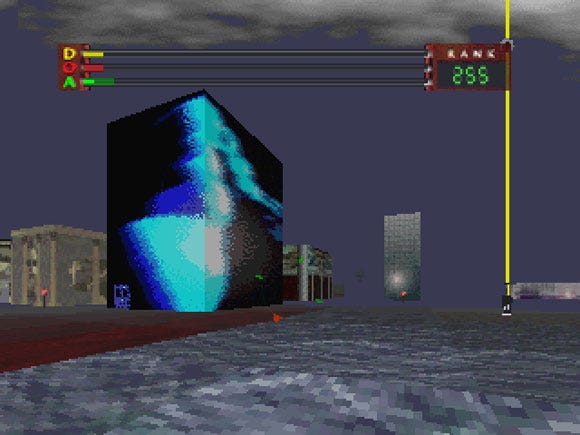

Given the 3DO's comparatively low install base and the fact Immercenary was a system exclusive, very few actually played it. The game's premise is that through astral projection, scientists are communicating with a future Earth, where an enormous virtual reality network known as Perfect has trapped humanity. The player, a psychic virtual reality soldier, has their consciousness projected into the future, into Perfect, in order to shut it down and free everyone inside.

To an observer the game may sound like The Matrix film -- which came years later -- crossed with the aesthetics of the schlocky early 1990s VR film The Lawnmower Man.

As Johnson-Norris confirmed, the team was influenced by popular media. "A main inspiration was the book Snow Crash, by Neal Stephenson. The book kicked ass! It was like Matrix long before Matrix. We watched tons of sci-fi movies and read graphic novels for inspiration."

For Johnson-Norris, the growth of the real-world internet also affected the team: "We wanted to contrast that dirty, real-world grunge feel -- seen in the game 'wake up scenes' with the old barn and slow-moving fans -- with the high tech, fantastic virtual world.

"We loved the idea of the player moving back and forth. The virtual world was seductive, and being a super hero avatar felt great. Leaving the 'real world' was not hard, even though it came with a hidden cost: the loss of freedom and self-determination."

Functionally, the game is closer to Wolfenstein 3D, taking place on a flat plane, rather than Doom, which gave the illusion of height through stairs and elevators. What makes Immercenary distinct, even today, is that it takes place over an enormous, evolving city, which continuously streams from the disc (at a rough guess it covers one square mile). There are no loading areas, unless you enter a building where a boss resides.

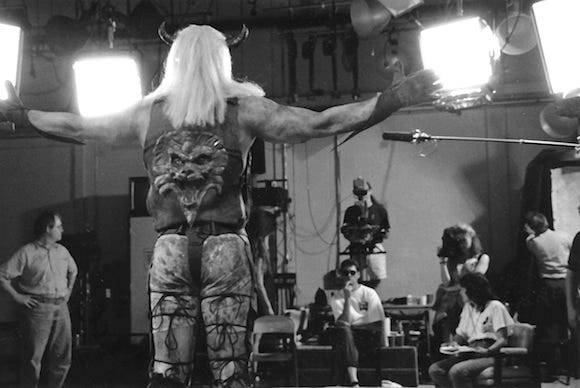

Populating the city are 255 ranked enemies, known as "Rithms" -- as in algorithm. These enemies are split between five lower-ranking divisions (ranks 255 up to 12), and then eleven bosses comprising ranks 11 up to 1. Kill a Rithm from any division, and they are dead -- permanently. This means it's possible to whittle enemies down until the city is depopulated. There's also a 256th ranked enemy called a Goner (because it's made of polygons), but these are infinite and randomly respawn, acting as generic fodder.

Given the intrinsic nature of the pseudo-online component, I asked Stashuk what everyone's exposure to the internet, and the nascent online games space, was. "We felt a strong connection to the future of what we now know to be 'online'. Though the internet was still in its infancy, there was enough suggestion to its phenomenal potential. As far as traditional gaming, we were all into playing D&D and other role playing games. I think some of that intellectual play also made its way into Immercenary."

Given the intrinsic nature of the pseudo-online component, I asked Stashuk what everyone's exposure to the internet, and the nascent online games space, was. "We felt a strong connection to the future of what we now know to be 'online'. Though the internet was still in its infancy, there was enough suggestion to its phenomenal potential. As far as traditional gaming, we were all into playing D&D and other role playing games. I think some of that intellectual play also made its way into Immercenary."

For those fortunate enough to play Immercenary, there is indeed a noticeable RPG connection: killing enemies releases a patch of visible, snowy static, which when collected acts as XP and raises your stats for Health, Attack, and Stamina. The goal is to take out the lower ranked enemies until you're strong enough to challenge one of the bosses (each represented by red markings on the map).

Nebulous terms like "sandbox" and "emergent gameplay" don't describe it fully; apart from the final three bosses, you can go anywhere, collect any item, and fight anyone at any time. It's completely open. Enemy AI is also rather clever. Some enemies hunt in pairs, others surround themselves with the generic Goners as cover, and you'll even find different ranked enemies fighting each other while oblivious to your presence. It's a surprisingly effective digital ecosystem.

"I recall that we were always developing to achieve the most eloquent performance within the context of the new 3DO platform," says Stashuk. "Between the texture mapping and video inclusion, I think we really offered a rich experience. It's hard to see that now looking at the comparatively really low resolution, but at the time it worked." Indeed, while Immercenary may seem archaic compared to the best the genre now offers, in 1995 its blend of a surreal landscape, wide spaces, and complete freedom was legitimately impressive.

"We were looking to deliver a very cinematic experience," Stashuk says, "where mood was developed in both the psychological arena as well as the visual. Many people talked about an unusual magnetism to the game, which even found its way into their real-life dreams. Unlike other combat-based games of that time, this was definitely a different animal. I think in some ways the unknown was what was so compelling. The vastness of the city felt like an urban safari. This created an underlying sense of anticipation and stress, as you felt so exposed."

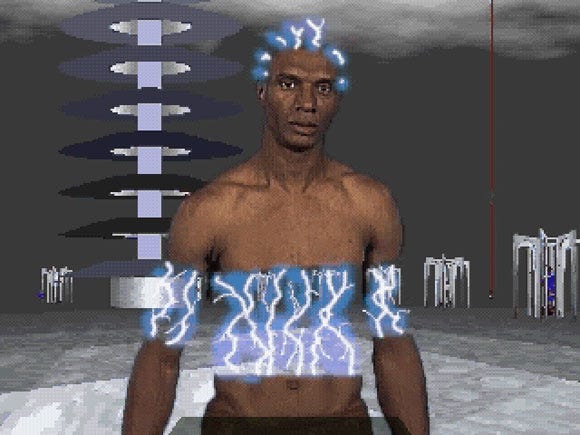

Counterbalancing this tension was the DOAsys, a neutral healing zone in the city's center. Here, the player could recoup in safety and chat with various online users, including bosses. Shown as filmed actors against a pre-rendered background, some spoke aggressively to reinforce their dominance, while others explained the world's background and gave subtle clues to defeating rival bosses. Each had a distinct personality based on what today would be seen as common internet tropes.

Interestingly, several of the actors were staff from Five Miles Out, including company co-founder JD Robinson, who filled the role of the player's predecessor, and who was shown on the back of the box. "I think we all enjoyed the experience of representing characters in the game," says Stashuk, who played the role of the Chameleon.

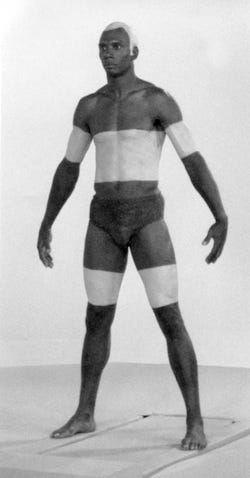

Johnson-Norris explains the intricacies of digitally transitioning actors into the game in the 1990s. "For the movement of the characters, we bought a treadmill and coated it in Ultimatte green paint. Our construction engineer developed a giant platform around it, like a pool deck, also in Ultimatte green.

"We rented a studio at our local CBS affiliate and painted our backdrop. We rotated the whole platform for each of the angles needed, and had our characters make their signature moves and runs.

"I'll never forget going through all the frames to pick the right ones for the motion. The characters were so creative, and offered lots of options for fun voices and moves."

For Johnson-Norris, the game's creative success was also due to having a fantastic team: "Our planning process, led by Ken Hubbell, and game story, written by Elton Pruitt, kept us on target. Christopher's design of the characters and environments was spot on -- ambitious for the time, but realistic in terms of development.

"JD was brilliant. We also had a great make-up artist, Mitch Gates, so were able to make our characters come to life. The coders were focused and talented. Our contact at EA, Jim Simmons, helped us develop a realistic game plan, no pun intended. Everything went really smoothly -- on time and on budget."

The company was never able to work on such ambitious project again. " "We developed some small games for EA after that, but nothing on the scale of Immercenary," says Johnson-Norris, who notes that as the publisher grew internal studios and acquired other developers, it "stopped outsourcing development to teams like Five Miles Out."

As Stashuk explains, "After Immercenary was published we started on another game called Shattergrid, which involved a spacecraft you piloted in sub-atmosphere/urban environments. We did a short demo, and I did an intro sequence and modeled the spacecraft as well. We looked to EA for publishing, but a contract was not realized. This time period saw the short-lived 3DO platform already falling away." The developers transitioned their business away from development and into an internet service provider.

"There was a lot of interest in us creating a PC version of Immercenary," says Johnson-Norris, "but since the game was specifically designed to show off the 3DO, it wasn't realistic." Due to low sales of the 3DO and therefore a small audience, Immercenary failed to influence the FPS games that followed. Compounding the tragedy of its obscurity is that while the freely downloadable FreeDO emulator for PCs will run commercial 3DO discs, it can't emulate Immercenary correctly, resulting in lost textures and frequent crashing. Anyone curious to play it has to purchase a 3DO system.

I asked the two former Immercenary creators what their enduring memory is. Says Stashuk, "I think the way in which we all fed off of one another's creativity and went about this production in such untraditional ways led to a unique product. We were not a well-established mega studio, but a small team of passionate people. I am proud to have been a part of such a dynamic team and to have shared and learned so much."

"Five Miles Out was in an old house where the rooms were all connected," says Johnson-Norris. "I recall Christopher blasting some rainforest music while he, the other graphic artist, and the coders all worked at their computers. It was just a great feeling. Another favorite memory is of the Mac station I had in my bedroom, so I could render scenes while I slept. I would set my alarm to wake me when it was time for a scene to be fully rendered, wake up, make some edits, set to re-render and go back to sleep. Good times!"

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like