Life is Strange: A Retrospective

Over seven years and five games, the Life is Strange series has covered a lot of ground in narrative innovation.

Today marks the release of Life is Strange: Remastered, a new collection consisting of the first two games in the Life is Strange series, now visually upgraded for a new console generation.

A lot has changed about the games industry since the first game debuted in 2015. But the writing and narrative innovations that made it special still stand out as some of the best in the business.

In light of today’s release, as well as the upcoming debut of Life is Strange: True Colors on Nintendo Switch in February, let’s look back at Life is Strange and how each of its five games over the years have helped cement its legacy.

Life is Strange

When Life is Strange was announced in August of 2014, it quickly became a media darling on the basis of its novelty. At the time, it wasn’t as common to see a female queer protagonist in a video game, and Max’s plight, that of a teenager navigating the social travails of being the new girl at school, was one that almost anyone could relate to.

But beneath the game’s charming outward trappings, its soft natural sunlighting and sentimental Sufjan Stevens songs, was a lot of heart. Max Caulfield, a young photography student, returns to her hometown, only to find out you can never truly go back home again, encountering vicious social drama, the disappearance of a local teenage girl, and the reluctant pushback of Chloe Price, the best friend she left behind.

Supplementing Max’s struggle is her ability to rewind time, a power that not only could spare the ones she loves from certain death, but also facilitates branching story paths, making each experience unique to the individual who plays it. It also, in letting Max ruminate over each of her decisions, reinforces the game’s themes of regret, uncertainty, sacrifice, and heartache. With each agonizing choice came consequences both foreseen and unintended, and with each of Max’s failures and triumphs, we project perhaps our own desire to go back and do it all, all over again.

Fittingly, Christian Divine, in the 2016 GDC talk Life is Strange: The Blue Age of Storytelling, cites young adult author Judy Blume as an influence on his writing, perhaps explaining the sympathy shown towards the game’s young subjects. This too is illuminated further in the 2016 GDC talk by co-directors Michel Koch and Raoul Barbet entitled Life is Strange: Using Interactive Storytelling and Game Design to Tackle Real World Problems. From the get-go, the series established itself as a platform for empathy and earnestness, and that thoughtfulness is evident in the process.

Life is Strange: Before the Storm

Rewinding the time of Life is Strange to an era before the first game, Before the Storm was saddled with a difficult task. Its studio, Deck Nine, both had to follow up the critically acclaimed original with a smartly written prequel but also find another narrative innovation to deliver its story in a unique way. For this, they created the Backtalk device, which would, similar to Max’s “time rewind” power, give the narrative a few branching paths that would affect the game’s outcome but also reinforce its themes. As an angry young teenager, will you escalate the situation or diffuse it in hopes of keeping the peace? Whatever your approach, futility and frustration are felt with every decision.

In Before the Storm, we not only get to see Chloe at a time preceding Max’s return to Arcadia Bay (and before she adopted the blue hair look), we also meet Rachel Amber, the young woman whose disappearance haunts the original game. The relationship that builds between the two, Chloe’s anger as she deals with school and her meddling stepfather, and Rachel’s pain as she learns the truth about her family--all speak to a deep understanding of what it is like to be a teenage girl seeking connection at a time when she feels so trapped and powerless.

Perhaps helping Deck Nine flesh out their vision of female teenage growing pains amidst small-town life was the diversity of the writer room. Deck Nine’s Zak Garriss, in his 2018 GDC talk Productive Dissension: How a Diverse Writers' Room Created Life is Strange: Before the Storm, cites “productive dissent” in the writing process, saying that, combined with an equitable and structured writing process, the game was better equipped to be authentic and reflect a broad range of experiences. Personally, having once been a troubled young woman growing up in the Pacific Northwest, I saw much of myself in both Chloe and Rachel. While Deck Nine had a challenge in emulating the original game’s style, in many ways they rose to the occasion.

The Awesome Adventures of Captain Spirit

As a short, in-between title, The Awesome Adventures of Captain Spirit may not be considered by some to be an official Life is Strange game. But it served a vital purpose in the series’ progress nonetheless. Written initially to facilitate new technical features with the development team’s switch from Unreal Engine 3 to Unreal Engine 4, the demo allowed DONTNOD to build on the conventions of the original as they prepared for the upcoming sequel, Life is Strange 2. This included a narrative mechanic that embellished on the inner monologues of the previous games: like his predecessors, the game’s protagonist, Chris, interacts with items in his environment by sharing thoughts and perspectives that add to our understanding of him as a character. But in Captain Spirit, there’s an additional layer of interactivity that allows the little boy to channel his imagination as he connects with the world around him. Ordinary objects are turned to the props of a wild inner fantasy life, transforming him into a superhero with powers of his own. As we learn more about Chris, we see a metaphor for the safety he finds in that magic filter, and the shelter it provides from his physically abusive father.

The chapter also reinforces the series’ signature use of crossover and tie-in events, hinting at things to come in the subsequent Life is Strange sequel. While short, it’s also perhaps the most difficult story to play within the Life is Strange games, with an impact as large as any of its full-length peers.

Life is Strange 2

Upon the game’s announcement in May 2017, there was some initial pushback over the change in characters for Life is Strange 2. After all, who could forget the climactic conclusion of the original game, and what it meant for the fate of Max and Chloe (and simultaneously, all of Arcadia Bay)? Did their love and friendship endure? Would we ever find out what happened to the town?

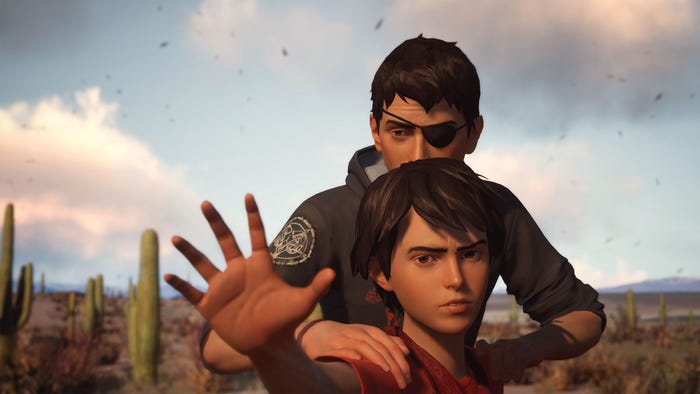

But the sequel’s story, that of two young Latino boys navigating the cruelty of white America, was just as important, relevant, and poignant as that of the original. At its start, we see the Diaz brothers, Sean and Daniel, have a deadly encounter with police that functionally renders them orphans and sets them towards life on the run. Subsequently, as they hide themselves from the authorities (and Daniel’s special powers from everyone else), we find themes of alienation, familial sacrifice, and living off the grid, against the backdrop of greater social issues like child abuse, abandonment, and police violence.

Life is Strange 2, like Captain Spirit, is one of the series’ cruelest games; even its happier endings are tragic. But the tragedy is suiting, in that, for many people, happy endings are the exception, not the rule. In that sense, the sequel might be Life is Strange’s most honest game, too.

Life is Strange: True Colors

The latest release in the Life is Strange series sticks to many of strengths of its predecessors, while also allowing Before the Storm developers Deck Nine to fully step in to guide the future of the franchise. Alex Chen's story begins as she travels to a rural Colorado mining town to reconnect her last known family, the brother that she hasn't seen since she entered the foster care system as a child.

Its through this uncertain new chapter in her life that we're introduced to Alex's immense capacity for empathy, and her at-first reluctant ability to mirror the strong emotions of the people around her. At onset and for the years before we meet her, Alex's power brings her nothing but trouble, forcing her to experience others' powerful emotions. As further tragedy strikes in that small mining town, Alex grapples with her place in the world and slowly finds herself opening up to the small group of friends that unwittingly teach her that her power of empathy, long thought of as a curse, is truly a gift that allows her to truly understand the people around her it like no one else can.

With mechanics once again perfectly paired with narrative elements, players then experience the fear, anger, sadness, and joy of True Colors' tightly-knit cast of characters, giving them the tools to explore those relationships and stories, and to ultimately solve the dark mystery hidden within this seemingly sleepy town.

The difficult space between a character showing apprehension about their abilities and the game encouraging its players to use those powers was something the game's writing team to special care to navigate. In a conversation with Game Developer, senior staff writer Felice Kuan explained that "When you give the player a power and the character has mixed feelings about it, you can find yourself in a bind where the character is saying 'I shouldn't use my power. it's bad to use my power, like shame on me.'"

Writers looked to the characters that were becoming more and more important in Alex's life to help both her and players overcome that deliberate emotional hurdle. "We really did want a character who had mixed feelings about [her powers]. But we tried very hard to give her good reasons early on to embrace it," explains Kuan. Deck Nine's previous experience with Life is Strange: Before the Storm, as she explains in the full interview, was also key to understanding each character on an emotional level, and ensuring whatever twists and turns their stories took, good or bad, still felt distinctively human.

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)