Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

2K Boston/Australia's BioShock is a key game in the evolution of gaming narrative - and in this in-depth Gamasutra interview, creator Ken Levine expands on his GDC talk to reveal just how it was put together.

The evocative 2K Boston/Australia developed first-person action title BioShock is renowned for delivering one of the most compelling narratives yet seen in gaming. And, at Game Developers Conference this year, co-creator and former Looking Glass Studios (Thief, System Shock 2) designer Ken Levine delivered a packed presentation on the techniques he used to make gamers care about his storytelling.

As the nature of game narrative evolve, gamers, critics, and developers demand more from themselves. As part of this evolution, Levine has decided to make an effort not just to improve game narrative - but to work to help the industry at large do so.

Thus, this in-depth Gamasutra interview, conducted the day after he gave his presentation, further explores the questions raised by BioShock's narrative devices and techniques, and brings to light some points that weren't divulged in the original presentation.

Christian Nutt: Your GDC presentation on narrative was well-received. Why do you think people are reacting so strongly to the narrative techniques that you employed in the game -- developers and gamers, both?

Ken Levine: The meta-question on narrative is, are we going toward this parallel model, which is "game, cutscene, game, cutscene, game"? Because it's a bit odd, if you think about it. It's an artifact from when our world was simple. I talked about wheat and chaff yesterday -- when we could only render the wheat. The cutscenes take up a lot of chaff space, because of storytelling stuff and little details and subtle emotions.

I guess you have to step back and look at and actually really look at... not where we should be, but where we're going. Are we more toward parallel structure, or more toward integrated structure?

I think the answer is the integrated structure. It occurred to me that I was fortunate to both make a game during this time period and start formalizing a discussion about this topic. I think it's easier once you have some credibility of making something that demonstrates it.

To talk about another GDC thing, it's always tough for people to ship games without having the opportunity to talk about things, because they can't demonstrate them... If I died tomorrow and I never said another word on it, you'd have the game to look at, and think, "Well, at least this is what that idiot was thinking." I was trying to formalize my thoughts, and I made the game into a presentation to share with colleagues so they can see the thinking behind it.

I was struck by, when you were talking, you said that people often come up to you and say, "Look at Square Enix. They can do Final Fantasy. They can do these cinemas." My response to that was, "But look at what they pour into being able to do that," in the sense that they stand out from the crowd in a lot of ways. They concentrate on that, and they hone that. I don't know. Maybe that isn't even a question. Maybe it's just an observation. I think that when you're talking to people about these things, context is important.

KL: Well, there are cost issues. Obviously... think about what it costs us to get to Dr. Steinman, versus how Square would do it. I think we would do it a lot more cost-effectively, and we can do it integrated into the game experience. Now look, I'm not blasting whatever they do. Clearly, they know what they're doing, and they do their own kind of thing. They're the best at what they do and how they do that.

KL: Well, there are cost issues. Obviously... think about what it costs us to get to Dr. Steinman, versus how Square would do it. I think we would do it a lot more cost-effectively, and we can do it integrated into the game experience. Now look, I'm not blasting whatever they do. Clearly, they know what they're doing, and they do their own kind of thing. They're the best at what they do and how they do that.

The question I'm asking more is what excites me as a game developer? Exploring this space, or exploring the parallel space? The answer may be for any particular game developer, the parallel space. And God bless them. Go forth and prosper. I think, though, that games are uniquely their own media. It's about exploring the integrated space.

Mathew Kumar: I was kind of interested in BioShock, especially because you explore the illusion of choice within games, as the metastory. It's over and above that. One of the things that interests me is that there's a point where you realize that's what's happened, but after that, you're not actually given any choice! Could you talk about that part?

KL: This is one of the things that was really interesting. The reaction totally surprised me after the game shipped. Both to have successfully worked with that scene with Ryan, that people got it. I was worried people would be baffled by it, be like... "What? I can't fight Ryan and jump on his head three times to kill him?" A boss battle.

But also the reaction afterwards... that A, we didn't have that part, and we had a mystery, and B, some people had an expectation that now that we've rubbed your lack of freedom in your face -- not just in BioShock, but in all games -- sort of postmodern, rubbing in the face, that we didn't open it up to give people more freedom. That would've required a vast implementation in the game design and things like that.

It never occurred to me that this would be an issue with people, that by having this thing which happens in the narrative space, you'd expect this giant change in the gameplay space. I think that looking back on it, that's something that I'd want to give a huge amount of thought to, but it was more like, "I think this would be a great commentary on games, and the world of BioShock as well." I didn't realize that it would change expectations.

MK: You didn't expect that people would understand the level at which the gameplay and narrative would be integrated by that point. Was that always the plan, to make this the meta-second level of integration?

KL: It wasn't always the plan from the start. I always wanted the notion of the unreliable narrator, which is a concept that I certainly didn't come up with.

CN: One of my favorite examples is Lolita. I'm sure it goes back beyond that.

KL: There's a million great movies out there that inspired that. Lolita, and The Manchurian Candidate, Fight Club... all these things that make the audience go... Rod Serling stuff. The Twilight Zone. It's the unreliable narrator.

It hadn't really been brought into games all that much. We did a little bit of it with System Shock 2, and I really wanted to explore that space here. It's about... I didn't mention this in my presentation, I keep forgetting to... it's about damaging not the character, but damaging the player. I think insulting the player is something... to put the knife in his back, not just the character's back. Because every game has the knife go in the character's back.

But if your perception of reality is screwed with, and you're basically played for a sucker, people have an emotional response to that. It's like when you read people saying, "I just put down the controller and walked away from the game for a minute." That doesn't happen when your character gets thrown off a roof and knocked unconscious, or gets shot at and wounded.

CN: Or dies.

KL: Or dies. Yeah. It happens when the player is engaged, when it becomes personal to the player. I think we wanted to do that. The particulars we worked out... are complicated, but I've always started with this goal of wanting to do that.

CN: Other games have toyed with this, in the sense that Eternal Darkness toyed with the idea of changing it more to a, "what you see on the screen isn't really there" perspective. I think there's a lot of work to be done that can toy with what games can do. Like, you can have collisions with objects that aren't visible, or you can have graphics that look like one thing, but in reality...

KL: Denis [Dyack] asked a question at our discussion at DICE.

CN: Yeah, I was there.

KL: I wanted to give him a little shout-out, because that was a lot of inspirational stuff in Eternal Darkness. I think you have to be careful with how much you do it, because once it becomes the norm, that the narrator's unreliable, you kind of have to do it in a rush, all at once. Well, not in a rush, but in a moment, and then blow the player away with that. Because by the eighth or ninth time that happens, it's no longer unreliable narrator -- there is no narrator. And you're like, "Stuff's wacky here."

It could become the lens flare of narrative.

KL: Yes. Yes. In BioShock, it's basically all held back. We built it up and we built it up and it all got released in this one moment. And that was good. I think if we had to do it again, it would've been tougher, in the context of that game.

You're talking about how the concept of the unreliable narrator is prevalent in film, but you're talking about how our medium has to have its own forms of storytelling. Rather than taking cinematic techniques from film, do you think that you could take concepts? You're talking about mise en scene as well.

KL: Mise en scene, the unreliable narrator... all these things we take out of film. I'm not sure if like... okay, in Fight Club, he turned out to be himself, or he didn't turn out to be a different Tyler Durden. Spoiler alert! Not direct content, but concepts.

What I'm more saying is, if you don't want to do traditional cinematics, what can you take from film?

KL: Well, storytelling techniques, like the ones I've been describing. The element of mystery. They leverage mystery... games have a very sort of nerdy way of having to explain everything to people. Mystery can be your friend. I've talked about Cloverfield being Godzilla minus information. It reinvented a genre by just... it's exactly fucking Godzilla, right? What's the difference? A giant monster comes to a big city and destroys it.

MK: I've actually never been more annoyed by it. It would be like, "Oh my god, are you seeing this?" and the camera would be in the opposite direction.

KL: Again, I think it will go through a popular reception to it. Imagine if it was just... cut to the generals talking about Cloverfield. "We've got to get that monster. Send in the infantry!" Cut to the infantry preparing and coming up. Would you have preferred that movie?

MK: Well, not necessarily, but it felt like a tech demo to me. I felt like the narrative of the characters that we were watching was terrible, whereas I was impressed by what they were doing.

KL: Separate from whether the execution of the characters were to the best degree, the concept, I think, opens up new and exciting possibilities for storytelling in the film space. I think Lost -- and Abrams is involved in both of these things -- Lost is basically the concept of "don't give the audience information. Withhold information." That's the entire show! What does it have when the secrets are out? All those Japanese horror films. That's something too, where removing information can be a really powerful thing. Mystery stories are games. You're actively engaged in the pursuit.

CN: It's interesting. What's striking to me about BioShock to an extent is that there are things like Little Sisters and Big Daddies and science fiction elements, but in a sense, it's still real people and regular people. Not super commandos, and not Marcus Fenix. Outside of, say, Silent Hill, it's still unexplored territory.

KL: Well, I think... talking about another theme, the horror theme, that the game had, it's really hard to do horror with superheroes, because you have to relate to them. You have to put yourself there.

I think the thing that all horror is based upon is loss, right, and what you're afraid of losing: family, property, and sanity. BioShock's story is "loss, loss, loss." Loss of dreams, loss of hope, loss of love. That's what makes it horror. That's why one of the first horror things you see is the woman with the baby carriage. There's no baby in there. She's lost her mind, and she's lost the thing she loves.

MK: There's a part that stands up to that in the design, where you'll see the shrine to the dead.

KL: We wanted to talk about... me, I saw these scenes on the highway. It's very haunting, where you have an accident and there are flowers and everything. It's so sad, it's touching. We wanted to make sure that would happen in this world. It's terrible. People respond in a human fashion, and that memorial was a response.

It's that human part. Diane McClintock, her purpose is to show the human face of all this as the woman who risked her life. That's her purpose -- to show the impact of the war and the Little Sister experiments on the average man. Without that empathy, you don't have horror. I mean, if you're complaining about Cloverfield, you didn't feel the empathy for the characters.

MK: Yeah, at all. Like, they were yuppies who were living in a flat that's ten times better than what I live in, so I'm like, "What do I care about them? I want these guys to die."

But when it comes to establishing empathy in your game... I see the empathy in the scene with the baby in the carriage. I see she's frightened, and I see these people are warped and damaged. But what interests me is that within the space in which the player controls the rhythm in which he sees things -- horror in cinema is always based on a beat, almost. How do you control that with the player?

KL: You can't. You have to give that up that to some degree. I talk about trusting the player a lot. Information is not your friend with horror. It's missing things. One thing that people on the team kept saying was, "Shouldn't we lock the player in place? What if they miss it?" I said, "That's okay if they miss it. The thing out of the corner of your eye is way scarier than the thing in front of you."

There's this great moment Paul Hellquist did in Medical when you go to pick up a goodie, and you sense somebody's behind you, and you turn around and there's a doctor standing right in your place. That was the only jump out of your seat moment in the game, and I really... I never jump out of my seat. I remember having that moment of, "I think there's something behind me," and turning and having this thing so close to you. The scariest moment was "I think there's something behind me."

I know that you can't control it. I don't know if everybody had that feeling, and we can't control that, because we don't cut to your own face going [Levine makes a scared face]. There's a lot of trust in the player, and a lot of faith in yourself that you're going to point the player in the right direction.

It's still a lot of work underlying when you want them to look at something. Great example: the theater where you first see the Big Daddy and the Little Sister, the Big Daddy rescues the Little Sister, and pins the Splicer through the wall and puts a drill through him.

Originally, the background in that scene was way more crowded with detail, with all this stuff going on. It's like, "Take out all the detail. It's in a theater." We put the spotlight magically on the Little Sister. It happens to be on the Little Sister. There's a lot of artifice in BioShock, but that artifice, like in theater, is to point the eye without literally pointing the eye -- you're not specifically grabbing the player's head, like in cutscenes, but pointing the eye as much as you can.

CN: I like when you talk about is using the world as part of the narrative. I think you're right, in that a lot of games don't. I think that you're right in saying that a lot of games could, and in an effective way. You pick up the world as you play through it. It's doesn't have to be just office buildings. All you get out of that is, "Oh, it's contemporary," or whatever. You could pick up details of the world when you play a game, and it would save time and they're already making textures, so why not have them make meaningful textures?

KL: Yeah. There's a reason, like -- there's all these posters in the world, ads for products and propaganda and all these things. That's what I always wanted to do back on Thief. Put propaganda, and not occasionally, but fucking everywhere. The more of the content message that you can send that defines this world, the better. Let's fill this space with PSAs and ads and all stuff and little moments like the Sander Cohen statue and all those things.

If you can technologically, build that space. I did a big document. Here's all these things I want to tell. How do I get this information across? Sometimes it was Atlas talking to you, and sometimes it was a non-interactive sequence, like the Big Daddy and Little Sister one I told you about.

Sometimes it was fine to put it on a PSA, or a poster. Sometimes it was mise en scene. The most important things, we put them around the player and put them up high. The more optional it got, the more we could put them in these other spaces.

CN: You were talking about how the story had to come late in development to be as effective as it was. So was it seeing what the possibilities were in the levels that gave you the wherewithal to do that?

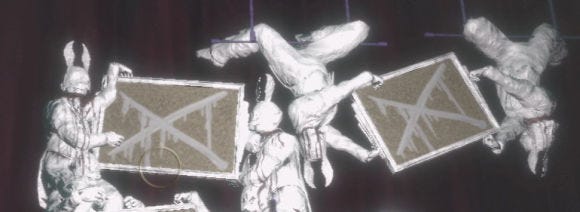

KL: I'll give you an example -- the Sander Cohen statues. They weren't my idea. They were Nate, Jordan and Scott. They did these statues, and I saw the statues -- especially the one where Cohen's sitting in this closet with a bunny mask on, sort of looking at you. I freaked out. It was like, "That's awesome."

It ended up in the poem he has. The theme of bunny being the emotional changes he was going through or whatever when he was hiding, emotionally, I just took that from those masks and then I wrote that poem. There are so many little moments like that where I'd be inspired by art.

If I kicked that script over the fence a year and a half ahead of time and wasn't day-to-day reviewing levels and feedback on levels and working on the design, I never would've had the opportunity to come up with all those ideas.

MK: The interesting thing is, though, that we're using mise en scene and so on, but in general, the way that films are made is that they are written, filmed quickly and put together in the end. But the plot is really set quite early.

KL: And the plot in BioShock wasn't set. The mission structure was roughly set. The changes to the mission structure were based on "this isn't working, gameplay-wise," and not "I need to do this, story-wise."

I had somebody ask me this question yesterday, about... at the Ryan scene, because it was animation syncing and stuff, I had to come up with that really early and had it pretty much locked in place. When I do a PSA or a new audio log, I had a lot more time to do that, to write and redo and redo that.

In the same way with film, when you get on the set, the director has free license with the script, generally. He has the actors there, he has the editing room, and he can turn it into a different film, essentially. And everybody expects the director to do that.

The challenge with game writers is that people expect writing to not have any bugs. And by bugs, I mean things that could be technically better. In BioShock, we just fixed a lot more writing bugs than many other games. Narrative bugs. That's putting in more stuff, taking stuff out, redoing stuff... I was able to generate most of those bugs myself, by observing the game under development.

CN: I guess the analogy I see is that it's like contrasting a film where the director works with the actors and says, "Ad-lib a little bit, work on your lines a little bit. We'll film extra. We'll film more takes." As compared to the film where they stick to the shooting script.

KL: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Every film has an editing pass. Every film has multiple takes to choose from. We don't have any of that. We have to do all those takes separately. Generally, if you rehearse a play, you're constantly fixing things in the rehearsal process.

In general, the position of the [game] writer is, "Give us a script. Thank you very much." No rehearsal, no chance the work with the actors, and no chance to rewrite based on the performance. If you want a great story, guess what? You have to think along these lines. It's just not the normal industry approach.

CN: I think this what this speaks to -- and this is increasingly common -- is the multi-disciplinary nature of working on a game. Say, somebody writes a play, and who doesn't direct plays. They sell the play, then other people take it up there and move with it. It's collaborative, but not directly.

KL: But very often with plays, the writer is there in the rehearsal period, rewriting, rewriting, and rewriting. Generally they have actors reading their lines and hearing them, and you go and rewrite based on that. None of that generally exists in the game-writing space.

CN: Right.

KL: It's kind of weird, when you think about it. Imagine if a programmer couldn't fix bugs, or people couldn't tweak spawn points or monster placement once they got feedback.

CN: To me, it's how BioWare considers the writers part of the design team. It's sort of synergistic.

KL: I'm president of the company, so I got to consider myself as part of the design team. I was lucky. Maybe if I was working somewhere else, it wouldn't have happened. I tell you, BioShock wouldn't have been BioShock if I wasn't able to be in there every day and be as dynamic. I was allowed such dynamism in the project in terms of being able to rewrite.

MK: Do you believe in the auteur theory for video games?

KL: In terms of one guy?

MK: People always say "Peter Molyneux" or "Miyamoto", and that's all we think of. It's almost a given that these people are thought of as auteurs. Do you think that actually the truth?

KL: I don't think that really is an auteur... You have to have one person at the end of the day who is responsible for saying yes or no, creatively. That's his job. You can generate content, and he has to look at the content and art, and he has to look at that and say, "This isn't working. This isn't right." And he has to be able to overrule people.

Talking about an auteur? Sure. I think you need that voice, otherwise you have chaos. It's the same way with every department, and the product needs that one person.

However, to think that all the great stuff comes from that one person is a totally different calculus. No. Great stuff comes out of a great team. You do need someone as the arbitrator of how to follow the product. Besides writing, that was my job on BioShock, as the arbiter of quality.

Fortunately, I had guys who were generally giving me a path to follow. In case we didn't, I had to say, "No, this is not right." That's something people need to hear, I think. You need somebody, right or wrong, doing that. The question is whether you've got the right guy or not.

CN: It sounds like the development of BioShock was atypical in certain ways. Obviously lots of games have a strong focus, have delays, and get feedback, but it seems like you tried to be responsive and tried to be a little bit naturalistic about your expectations of how to work on the project.

KL: I think one thing that made the product successful was... first of all, my business partner was Jon Chey. Read his postmortem on System Shock 2. He was the product lead on that. I was the lead designer. Jon and I had this relationship where he's got production issues, and I'm the guy who's got creative quality.

The fact that we understand what each other does and accept each other and trust each other... he'll say to me at times, "Dude, it's not going to happen." And I'll say to him at other times, "I think this has to happen, or we're not going to have what we want."

That natural, healthy tension is critical to any project, and those people need to trust and respect each other in order for it to work. A lot of times, they're going to duke it out, and one guy's going to say to the other guy, "Okay, we're going to go with your approach on this."

CN: What do you think about hard and fast scheduling? Obviously you do have to have a ship date and get the game out, and very typically, that's also based on market realities. You had to launch before the fall. I'm very sure that was your target, to get there before the fall.

KL: Originally, it was set in spring. We had a few extra months. Thank God for that.

CN: At the same time, if you had come out when Halo was out, you would have probably been steamrolled.

KL: Oh yeah. We probably would've been another beloved...

CN: You would've been like you have been in the past.

KL: I think that you have realities. We all have the reality. The reality of launching in the spring meant that we didn't get what we all wanted, and we were able to know that, "You know what? Come hell or high water, we're hitting this date, because all this work may not have a real return on it."

So I think that was a nice compromise. We found the right date where we had enough time to polish before we launched. We can always use more time. But I think this was a good compromise.

CN: What do you think of the importance of polish in games?

KL: Very important. Without it, it's the difference between... I've looked back at some of my old titles, and I realized how different BioShock was from them, primarily because of polish.

This article was first published on April 24, 2008. It has been updated in 2024 for formatting.

You May Also Like