Jim Brown's level design workshop: The illusion of choice

Jim Brown of Epic Games advises providing players with an “illusion of choice.” Bringing a behavioral science perspective, he argued for making choice illusory while preserving player autonomy.

Tuesday afternoon saw a fascinating GDC talk led by Jim Brown of Epic Games about how to create games that provide players with an “illusion of choice.”

This is a paramount concern because of how easily players can be overwhelmed by choices in a game, despite our never ending demands for choice in games. “Choice,” indeed, is a top-shelf buzzword for back-of-the-box blurbs for any number of games. It’s not just for RPGs anymore, either. A whole host of games now tout “choice” as synecdoche for realism.

Bringing a behavioral science perspective to his lecture, Brown made an argument for making choice illusory while preserving player autonomy. He drew a key distinction between player agency, which he defined as our capacity to choose, and player autonomy which he defined as our capacity to make informed decisions. In the case of the latter, he argued that autonomy was more about providing executive endorsement of the paths we had committed to.

The sunk cost fallacy, Brown argued, was easily exploited to compel players to follow paths laid out by developers. If players could be moved to invest a bit in a quest chain or the consequences of a given decision, they would continue down that path. “There is a huge sunk cost to creating a character and getting them to max level,” he said of MMOs.

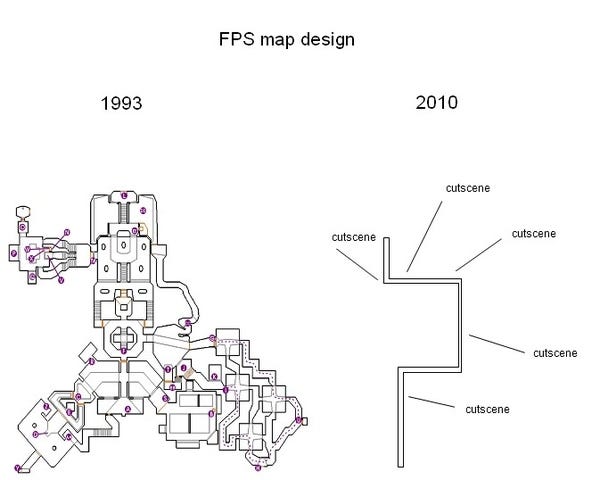

But if this sounds manipulative, the core of his argument seemed to be something many players could appreciate. He put up a famous graphic comparing a seemingly complex Doom level to a purportedly more linear level from a generic 2010 game where a corridor was punctuated by cutscenes.

The Doom level from the 90s, despite its apparent complexity on the blueprint map he showed, was entirely linear. But its blind alleys, keycard collection, and shortcuts gave the player autonomy: the ability to feel as if they are endorsing a path they had committed to voluntarily, even if they were being funneled in a direction that had long ago been decided up on by the level designer.

After all, popular multiplayer maps leave very little choice to the player and yet players love them, despite having only two to three possible paths to pursue across the length of the map, he argued.

He pushed back against popular advertising techniques that influence players and instead preserved their autonomy and enabled them to make meaning of the choices they were making. Crucial to this perspective is the idea that even if--as with the Thieves’ Guild quests in Oblivion--everyone’s technical path through the quest is the same, they are given the emotional tools to layer their own interpretations and meanings atop that experience. Brown is not advocating the callous manipulation of players, then, but a way to simulate the infinite choice of the real world without overwhelming the player.

One bit of the talk I found particularly interesting was Brown’s argument that tropes in games were the result of familiarity being psychologically pleasing to us. This, he argued, induced developers to resort to the timeworn cliches of, say, RPG levels set in city sewers, or parts of FPS levels taking place in air-conditioning ducts.

The converse of this was that players subconsciously both expect and like such things.

According to Brown, this familiarity has another side-effect as well: it compels players to make choices that comport with the expectations set by the trope. He pointed to Bioshock’s infamous choice between killing or saving The Little Sisters and gestured at statistics that showed the overwhelming majority of players saved them on their first playthrough. This, he argued, was because saving children was our comfortable and familiar way of dealing with the presence of little kids in such an otherwise terrifying environment. Intentionally or not, Bioshock’s developers created a highly winnowed choice that players could feel autonomously emotionally invested in.

Familiarity, then, can be seen as a shortcut to investment on the part of the player.

While I can’t say that I’m entirely sold on all of these ideas, they provide stark insight into how modern developers are thinking about choice, and why what’s going on beneath the hood of any given game is likely more complex--from both a technological and psychological standpoint--than many players might be giving their developers credit for.

Read more about:

event gdcAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)