How Green New Deal Simulator inspires hope in a climate changing world

The game provides accessible education on renewable energy transition, all with a simple deck of cards.

_copy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=95&format=jpg&disable=upscale)

Green New Deal Simulator is a card game where the player is trying to move the United States away from carbon emissions while still keeping everyone employed. It draws from real-world policies as it asks the player to work towards finding solutions to looming climate disaster.

Game Developer spoke with Paolo Pedercini of Molleindustrai, developer of this environmentally-conscious card game, to talk about creating a game around the solutions to the climate crisis, the route the developer took towards simplifying this complex subject into a card game, and the challenges that came from distilling such nuanced subjects into visuals for the cards.

Game Developer: Green New Deal Simulator is a deck-building game about climate change. What appealed to you about making a game like this? What inspired its creation?

Pedercini: There are plenty of environmentally-themed games coming out these days. What I’m personally missing are games and media that go past raising awareness of the issues and move toward raising awareness of the solutions, especially in the short term. The solutions to the climate crisis are not that obvious; they are not just technological fixes (solar panels, etc.), but also political, cultural, and infrastructural.

What thoughts went into creating a card game about such a complex subject? How do you make fixing the environment into a card game at all?

The subject is complex, but you don’t have to tackle every aspect of it. The game focuses on a specific scenario/location (the USA), a specific timeframe (the next two decades or so), and a specific set of issues (like the tension between decarbonization and employment). It also puts the player in a very specific role (the secretary of a new, powerful department), so you only have a big picture view. You don’t even fix the environment, really, because ecosystem restoration and disaster mitigation are not part of the game.

I call this process of reduction “rhetorical scoping” or “ideological scoping”; it’s like defining the scope of a game but taking into account expressive and political concerns along with technical ones.

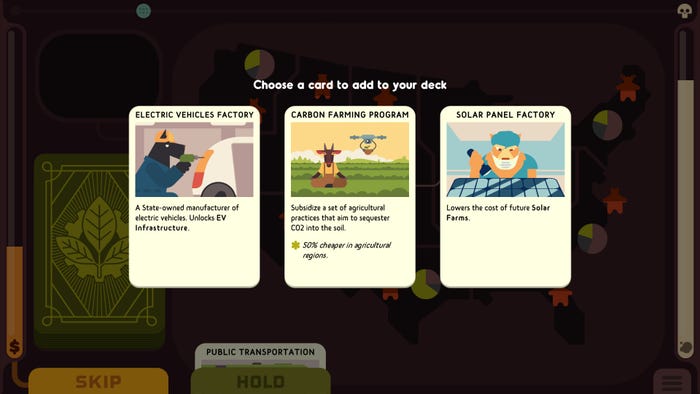

How did you turn the nuances of energy grids, green technology, and eliminating fossil fuels into cards that players could easily understand and put to use? What ideas went into taking complex subjects and distilling them into simple, but clear, cards?

I like the skeuomorphism of playing cards in video games because they instantly communicate aspects of chance and probability, as well as common affordances like “drag to play” or discard.

They are also able to represent heterogeneous actions. Had the game been a top-down tycoon game, things like public transportation, job training, or insulation retrofits would have been more difficult to visualize as objects you drop on a map.

The card illustrations are very simple but allowed me to complement the extremely abstract, zoomed-out map with a view from the ground. In pop culture we don’t have many representations of green collars: I’m talking about this new working class maintaining solar panels, practicing sustainable farming, manufacturing wind turbines, and so on.

Has the game changed a great deal over development? How has the game evolved over the course of its creation?

Green New Deal Simulator is the third attempt over the course of several years. The first prototype was nerdier and focused on the issue of intermittent renewable sources. Basically, you had to strategically place pumped storage hydropower, power lines, and redundant energy sources to make up for the variability of sunlight and wind. There was some sort of gameplay in there, but I worried it would have been enjoyed only by a German Energiewende bureaucrat.

The second prototype was a more traditional top-down builder: plop some turbines here, shut down a coal plant there, and so on. I quickly ran into the issue I was mentioning above: some actions don’t translate well into visual elements on a map.

Also, the action menu was getting unwieldy for the kind of casual experience I had in mind. That’s another design problem addressed by the deck-building gameplay: instead of choosing an action and then choosing where to apply it, the action is already chosen for you, so your choice is about where and not what.

I thought the limited agency made sense for the theme and the role of the player. You are not some kind of CEO of a green energy corporation. It’s implied that proposals from a variety of public and private entities land on your desk, and your role is to approve, subsidize, and plan them where they are needed.

The actual Green New Deal is very much about directing investments toward communities ravaged by deindustrialization, disasters, and by the effects of the energy transition itself.

Three of the deck cards from Green New Deal Simulator.

Why was it important that this be a simple card game that many players could quickly understand? Why not lean into an extremely complex take on the material?

I wanted it to be a sequel to the Democratic Socialism Simulator, which is based on one simple drag-and-drop interaction, has no menus, and no exposed numbers. Secondly, I’m also working on a bigger multi-year project and this was meant to be a short break from it. I allotted two/three months to the development of this game.

Thirdly, it may be tempting to think that the more complex a game is, the closer it gets to the slice of reality it claims to portray. But to me, there is simply no way to approximate big socio-economic systems. All claims of realism are misguided or delusional. Realism is an aesthetic—complexity an aesthetic. Together they convey a sense of accuracy and objectivity, but it’s a vibe really, a preference in the great spectrum of gaming experiences. I’m making art (or propaganda if you prefer), and throughout my 20 years of game development, I always adopted cartoony graphics, meta humor, and satire to underscore how games are fundamentally opinionated, biased, and subjective. The term “simulator” in the title is ironic, as in Goat Simulator.

What thoughts went into the visuals in order to make the gameplay clear and straightforward as well? What drew you to the visual style you chose for the game?

Games like these are really an exercise in information visualization, and I had to cut many interesting aspects of the energy transition only because I couldn’t find a way to present them to the player in a concise and clear way. On the other hand, I could have added a lot of traditional card game mechanics that would have made the game deeper and more fun, but they just didn’t have any thematic justification. That’s the self-imposed burden of the socially conscious game designer. It sucks.

Climate change is a difficult subject, but you have turned it into a fun game. How did you shape the experience into finding fun in healing the environment?

I don’t know if the Green New Deal Simulator is fun in the traditional sense. I wanted to convey a sense of hope and urgency at the same time. I wanted to present decarbonization as a compelling challenge that can be addressed in a variety of ways, and that produces all sorts of frictions and conflicts. The game has a puzzle-y feel because of its minimalism, but it’s more of a broken puzzle in which all pieces don’t fit perfectly.

The difficulty level is tuned in a way that even a “bad” player will get pretty close to winning, so it’s not too depressing when they lose.

Likewise, how did you preserve the learning in the game while still keeping things entertaining? How did you preserve it while making the experience easy-to-understand?

I think games can offer something that traditional narrative media cannot, which is a systemic perspective on systemic issues. Films, shows, novels, etcetera are primarily concerned with what fictional characters can do to change the world, or to survive in a changing world. They often involve stories about heroes and saviors making a difference under extraordinary circumstances. This can be good and galvanizing, but not everything comes down to what we can do as individuals.

Climate change calls for collective and institutional action. It requires slow, detailed, and often mundane interventions. That kind of stuff doesn’t make for good stories, but it can be the basis for good gameplay.

A gameplay screenshot from Green New Deal Simulator.

What effect do you hope it has on the player?

I’m hoping the game will get people more interested in the Green New Deal, which is still the only comprehensive proposal to address climate change in the US. It even has counterparts in other countries as well. I’d like it to be a primer on a series of lesser-known aspects of the energy transition, such as the role of infrastructure like high-capacity power lines and batteries. Or the distinct issues of electrification and renewable energy development: electric cars are pointless if the electricity is created by burning fossil fuels and, conversely, wind and solar won’t automatically take care of heating and transportation emissions.

Another thing I hope to convey is the importance of rural and non-coastal states, which have the most potential for renewables, but are also the most politically conservative in the current terrain. This is both an obstacle and an opportunity to achieve consensus on climate issues, because a just green transition means jobs and state-driven development in such regions.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)