How Undertale makes you think hard before killing monsters

'You kill lots of random monsters in every RPG and the consequences for this are never addressed. What if they were? I made a battle system where you could talk to foes and convince them not to fight'

"You kill a lot of random monsters (sometimes even humans) in every RPG and the consequences for this are never addressed. What if they were?"

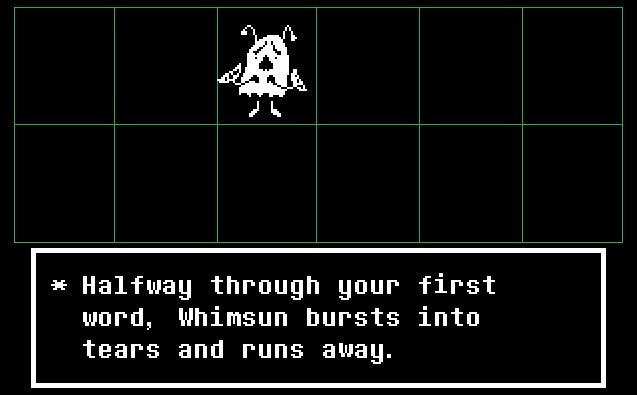

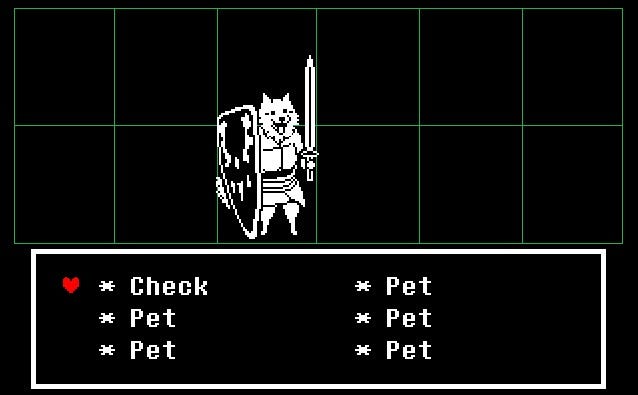

The monsters in Toby Fox's Undertale are an unassuming lot. Some of them want you to eat your veggies. Some of them want to know what you think of their hat. Some of them just want to be petted.

They're not exactly a fearsome bunch, but neither was that grinning slime many of us saw during our first few minutes with Dragon Quest decades ago. That didn't stop us from splattering it into smears of jelly for the miniscule amounts of EXP and gold it was carrying, beginning a streak of violence that has gone largely unchallenged in RPGs since their inception.

Fox asks us to question ourselves and the violence we commit in RPGs with Undertale. He does so by making the violence completely optional, asking that the player make a conscious choice to do harm.

Unlike the various slimes and goblins you HAVE to fight in many other games, it's entirely possible for the player to make their way through Undertale without harming a soul.

Where did this idea come from? "I always liked talking to monsters in Shin Megami Tensei," says Fox."So I started programming a battle system where you could talk to foes and convince them not to fight. When I started making the game the idea that you could beat it without killing anyone just evolved naturally."

"I started programming a battle system where you could talk to foes and convince them not to fight."

Beyond major bosses and a few scripted encounters, monsters tend not to have much story or character in RPGs. Shin Megami Tensei was one of the first to give the monsters some personality, allowing players to interact with them during a battle. Depending on what you said to a monster, they could join your party, provide you with a little help during the current fight, or viciously turn on you. Each monster had its own desires and needs; they weren't just beings that existed for the player to pound, but creatures with character.

Still, those monsters mainly existed for the player to beat up or run away from. Combat was still unavoidable, save for the occasional recruitment. Violence was still the rule of the game.

For some Undertale players, violence might very well still be the most useful option, as the ability to hurt and kill the monsters is still in the game. Despite making a game looking to subvert the need to fight monsters in RPGs, the option to do so is still there.

The beauty of the interactivity of games is in how the player chooses to act. Whether through combat, puzzle solving, or even just shutting the game off, the player is the agent of change and narrative in the game. The player is the main character of the story, and the decisions, even over something as simple as hitting a button, makes the player experience the game on a personal level. It's your story.

Having the Fight option meant the player had to consciously choose to use it or not. This wasn't a game where the only option was to talk your way through combat. The game didn't impose a peaceful lifestyle on the player. It left the option open for players to mull over when they're low on health. For them to keep glancing at when talk seems to be failing. To want to use when they're just sick of encountering enemies. The Fight option would always be there, tempting players to take an easier route and just cut their way across the game's world.

Fighting also awarded EXP, and was the only way you could earn it in the game. If you didn't fight monsters, you'd never get any more health. You'd never hit any harder. You would have to limp your way through some increasingly difficult encounters as you played your way through. End game bosses hit like trucks, too, and with each death, it'll tempt you to start fighting back. Not only is peace not the game's only choice, it isn't an easy one, either. Players will constantly struggle with the desire, and necessity, of violence in this world.

"You'll come across whole empty towns, their inhabitants killed by your lust for EXP."

When pressed as to why this choice was so important, Fox is mum. "This is the crux of one of the major themes of this game. Thinking about this while you play, an understanding will grow in your heart." It may seem like Fox is avoiding the question, but his game is asking players to think about violence. He is specifically asking the player to consider why they would choose it so naturally when endangered, or even when not. Undertale is not a game with a specific message on choosing violence, but rather sets up a framework for the player to explore their own feelings about it. Again, this is your story, yet not.

Still, Fox has created a game world that shifts dramatically if the player chooses that Fight option.

Undertale undergoes some serious changes in tone depending on the level of violence the player chooses - something far beyond 'good' and 'bad' endings. Many bosses in Undertale show up in later areas as NPCs if you let them live, so their absence has more of an emotional effect. They're not just pointless creatures you're killing, but real inhabitants of a living world. Push things even farther with basic enemies, killing them by the dozens, and you'll come across whole empty towns, their inhabitants killed by your lust for EXP. The music changes to something darker. The game makes no indication that you're turning Good or Evil, but it quietly judges you.

"Many factors further influenced development." says Fox. "The strongest one might be my desire to subvert concepts that go unquestioned in many games." Many games would take the time to tell the player they're doing something wrong. This tips the developer's hand, and makes choices easy. Do what gains you the most good points (or bad). You know what is good and bad in the game world. It's been made clear. Real life morality is rarely that simple.

If Fox was clear in his intentions, or if the game made a conscious choice to judge, the player would not need to think about it. As is, it's up to you to decide if talking to bosses as NPCs later in the game makes you feel like you've made the right choice. It's up to you to whether the empty towns and silent streets appeal to you or not. Fox has created a world that doesn't judge, but it does react, to your choice of violence.

"One fan of the demo said, 'I'd never played an RPG game where I never had to press the Fight button before...' That inspired me to try to keep that philosophy." The important part was not in making a game where no one had to get hurt. The important part was in choosing not to hurt - making the decision not to harm. It was in creating a world where violence came easy to the selfish. It was in building an existence where you could see all the monsters you could have killed living happy lives, and one where whole towns could be left barren wastes by your need for EXP. It was all up to you what you chose to do. It wouldn't be forced on you, but as the player, you would see what your actions had caused and judge for yourself.

"I like when people come to their own conclusions as to why." says Fox. Through choosing to put the Fight option in the game, he makes that clear. Fox sought to make players think about their actions for themselves by letting them see how the world reacts to their violent or nonviolent nature. Neither the game nor the developer would tell you if you were bad or not, but rather let you decide if the people of this world were worth saving. It created consequences for all of the fighting in RPGs by making the lives players took matter, giving them a presence in the world. It was just up to you to decide what you felt when the world changed.

Like the real world, no one might notice when you've done harm. You just might someday notice an absence where someone used to be.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)