Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Paul Hart and Lee Williams talk about designing a dungeon crawler around words and how they designed systems for combat and general play around players being able to type or say anything.

The IGF (Independent Games Festival) aims to encourage innovation in game development and to recognize independent game developers advancing the medium. Every year, Game Developer sits down with the finalists for the IGF ahead of GDC to explore the themes, design decisions, and tools behind each entry. Game Developer and GDC are sibling organizations under Informa Tech.

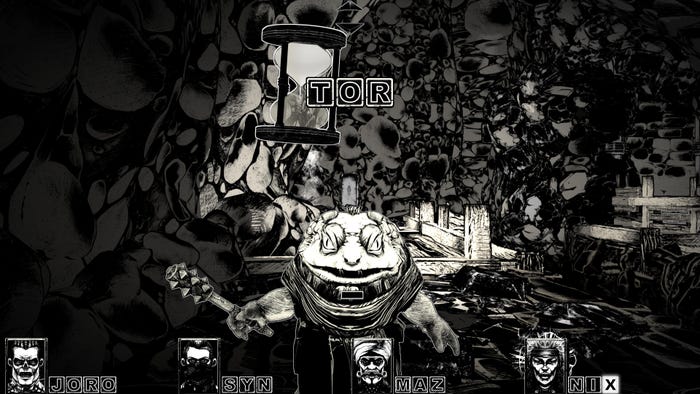

Cryptmaster is a dark dungeon crawler where your main weapons are your voice or your keyboard, as your ability to say or type whatever you want can unlock all manner of secrets and attacks.

Paul Hart and Lee Williams, the game’s creators, caught up with Game Developer to chat about how deciding to use words as the game’s theme opened up a ton of creative possibilities, the challenges that appeared when players could type just about anything into the game’s various systems and minigames, and what made a mixture of humor and horror feel right for the game.

Who are you, and what was your role in developing Cryptmaster?

Paul Hart, programmer, artist, and co-designer: I am Paul Hart, the programmer and artist and co-designer.

Lee Williams, writer and co-designer: I'm Lee Williams. I'm the writer and co-designer. I also provide the voice for the Cryptmaster.

What's your background in making games?

Williams: I had a whole bunch of other careers before games, but I wrote and published short stories as a sideline and I sort of drifted into games writing when I offered to write for free for a number of indie games that caught my eye. Paul was one of the first to take me up on the offer a good decade ago now and we've worked together on and off ever since.

Images via Akupara Games

How did you come up with the concept for Cryptmaster?

Williams: I'd love to say he came to me in a vision and demanded I make it, but the truth is a bit more mundane and messy. We started making a completely different game and through dozens of iterations it transformed into Cryptmaster. Making a game in which all the key mechanics involved words was the first step, and the theme, art style and story gradually evolved around that.

What development tools were used to build your game?

Hart: The game is programmed in Unity.

What appealed to you about creating a dungeon crawler around typing out or speaking words? How did this concept shape the mechanics and play style of the game?

Williams: The idea of using words came first and then the dungeon-crawling framework came later. We wanted to have pure keyboard controls, so that kind of grid movement made the most sense.

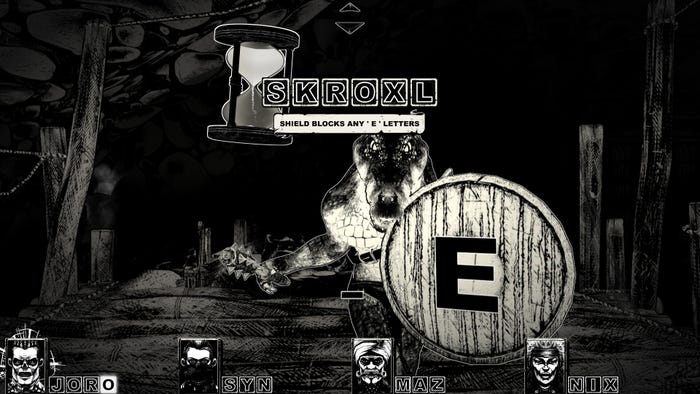

Once we'd settled on using words for everything, the ideas for mechanics just kept coming. We have variants on hangman, twenty questions, anagrams, riddles, etc. The health of players and enemies is represented by the letters in their names and the letters from collected ingredients are used to literally spell out potion recipes. There are just so many fun things to do with words and letters. I'd say we ditched far more ideas than we used!

What thoughts went into working typing/speaking into the combat itself? How did you shape battles to get players typing?

Williams: To be honest, it was never intended to be a game about typing. Words were the focus but the physical act of typing as a control method wasn't something we particularly wanted to explore. In fact, in the game's first few iterations the player would drag and drop words and letters with the mouse. Typing only muscled its way in once the mechanics changed so that it became the easiest way for players to input words and guesses.

Even in real-time combat, I think the challenge is more how quickly you can remember the words you need than how quickly you can type them.

Images via Akupara Games

Part of the game involves discovering words you can use in battle. How did you come up with this system? What challenges do you face in keeping things challenging if players can figure out these words in advance (or make some very lucky guesses)?

Williams: We knew very early on that we wanted all the controls to be typed instructions, so this meant any combat moves would also have to be typed. In early versions, the skills were all available from the start and upgrades would be for damage, accuracy, etc. Then we struck on the idea of having players guess the skills in a manner similar to Hangman, Wheel of Fortune, or Wordle. We knew this was the right choice when we saw friends and family playing the game and pausing for long periods to guess at words!

There is a cap on the skill words you can discover for each region of the game world, which ensures players don't progress TOO quickly through the guessing.

What difficulties do you run into when balancing the game around people's typing speeds?

Williams: To be honest, we haven't needed to do a huge amount of work in this respect. Typing speed is only really important during combat, so we have an optional turn-based mode to take the pressure off there.

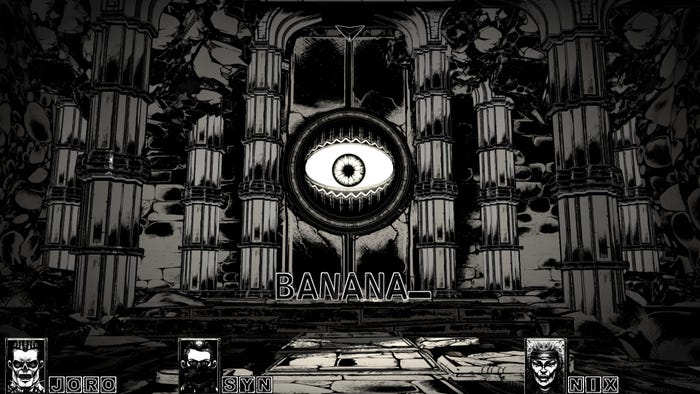

What challenges did you face in having to work with the endless possibilities players could type or speak to the game? How do you deal with all of that potential chaos?

Williams: The "trick" is mostly just a silly amount of work and persistence behind the scenes! I recorded more or less a whole dictionary's worth of words and spent hours second-guessing what players might type and coming up with responses…

We also have a simple system that's a little like a coin sorter. When the player types a word, the game checks to see if there is a unique response for it. If there isn't, it checks to see if the word is in one of a number of pools and sub-pools (verb, adjective, item, weapon, expletive, etc). If it is, it plays a specific response for that pool. If not, it plays one of a number of nulls.

The Cryptmaster will also sometimes spell out an unfamiliar word or say a familiar one as part of his response. Players understand that it's a trick, but the effect can still be pretty immersive.

Players will often have conversations and encounters with the title creature of Cryptmaster, as well as other monsters and beasts. How did you design the various minigames and encounter possibilities around the many things the player could do? How did you encourage players to cut loose with the things they could say or type?

Williams: Writing the game's conversations and encounters, I always had in my mind the idea of a sort of comedy double act between the player and the character they were talking to. I tried as much as possible to feed the player lines or set them up for jokes. What should I do with this object? How will you desecrate this altar? What is your most attractive quality?

Images via Akupara Games

Cryptmaster is filled with all sorts of surprising curveball activities. What thoughts went into adding all of these other activities players could take part in? What do you feel they added to the experience?

Williams: This sounds obvious, but our aim was always to make something fun. Sometimes the things you think will be fun just aren't. Sometimes it works the other way round. Very often, ideas that seem clever or inventive are tedious to actually play. We both have enough experience not to be too precious about our work and we're brutal when it comes to throwing out the non-fun stuff, however attached we might be to it!

Paul made a heap of minigames to add variety to the experience and the ones that stayed were the ones we found enjoyable to play. The card game in particular turned out to be much more fun than we'd expected!

What drew you to the monochrome art style for the game? What made it feel right for this game?

Williams: Once we'd settled on an old-school dungeon crawler with its roots firmly in the fantasy worlds of the 80s (D&D, Fighting Fantasy, Knightmare, Atmosfear, etc), it made sense to try for a style which would bring to mind the sort of fantasy illustrations that were common in gamebooks and manuals of that era. That was the thinking behind the sketchy, ink-on-paper vibe, and it made most sense for that to be monochrome. Plus, Paul was doing all the art himself, so it saved on felt tips!

Cryptmaster feels like it dances between being horrifying and hilarious. Why did you design it this way? What made this mixture feel right for the game?

Williams: My influences when writing Cryptmaster and providing the character's voice were all very much from that tradition of self-aware spookiness that has a foot in both camps. The game's mechanics are far too goofy and playful for it to work as straight horror, so the mood is closer to something like an old B-movie.

You May Also Like