Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

How do you approach writing romance in games?

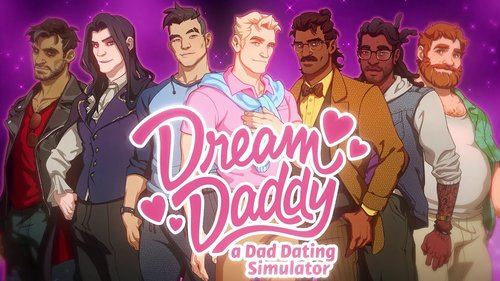

An interview on writing romance, featuring Samantha Wallschlaeger (Guild Wars 2, Mass Effect: Andromeda, SWTOR), Ben Gelinas (Speed Dating For Ghosts, Dragon Age, Mass Effect), Ed Sibley (miniLAW, Love Island), & Jared Rosen (The Tingler, Dream Daddy).

What follows is a roundtable discussion among game devs about how to best approach the challenges of writing meaningful romances in games.

Featuring interviews with Samantha Wallschlaeger (Guild Wars 2, Mass Effect: Andromeda, Star Wars: The Old Republic), Ben Gelinas (Speed Dating For Ghosts, Dragon Age, Mass Effect), Ed Sibley (miniLAW, Love Island), & Jared Rosen (The Tingler, Dream Daddy).

Originally featured at gregbuchanan.co.uk/newsletter. Follow @gregbuchanan (No Man's Sky: Atlas Rises, Paper Brexit, Trailblazers, Aquanox: Deep Descent) for updates.

Samantha Wallschlaeger (Guild Wars 2, Mass Effect: Andromeda, Star Wars: The Old Republic)

I grew up on older Japanese visual novels, which used romance solely as a form of fantasy fulfillment for the player. Audiences expected each romance arc to follow an existing trope, and the games of that era were happy to oblige. And there’s nothing particularly wrong with that, but it frustrated the hell out of me, because it was fantasy fulfillment at the expense of character development. A romance should reveal character depth, not hinder it. So when I began writing romances for games, I made a conscious decision to approach the process differently.

An NPC-player romance arc is always going to be a form of escapism, but I don’t think it has to give players absolutely everything they want. It’s important for me to follow a character’s truth, and really dig into the unique way he or she feels and expresses love. When I wrote Avela Kjar’s romance for Mass Effect: Andromeda, I knew that despite being kind and expressive, she would never allow herself to fully fall for anyone. And I stuck to that, even though it would mean letting the player down in the end. And that’s just it—it’s okay to break the player’s heart a little, if it makes for a better character experience. Injecting that kind of nuance into a relationship makes it feel more real, and lets the player become more immersed in the experience.

That’s not to say I don’t use tropes when I write romances. I think they’re an excellent starting point—people like them for a reason, after all (enemies-to-lovers is my particular weakness). And in order to provide a new spin on classic tropes, you need to be a practiced study. I make a point to grill my friends and colleagues on why they enjoy particular kinds of romance arcs, and what they’d like to see done differently.

Even if a certain kind of romance isn’t my personal preference, it’s important for me to understand why it’s appealing to other people. It’s my job to provide every type of player with the experience they’ve come to love—injected with a little freshness to surprise and delight them, of course. Because being committed to realism in game romance also means being committed to inclusivity, and celebrating the myriad types of relationships that exist.

Ben Gelinas (Speed Dating For Ghosts, Dragon Age, Mass Effect)

When writing romance, I start with everything but romance. Strong stories spring from stronger characters, who in turn spring from the strongest setting I can muster as a “writer” of “video games.”

So I start there. With the setting. What’s compelling about it? What haven’t I seen before... or more realistically, what’s a weird way to bounce around concepts that've been otherwise done to death?

What are the rules of the setting? The inherent conflicts? By answering these questions, I start to understand who would call the setting home. Paragraphs, sometimes entire pages, follow that only my collaborators and I will ever see—exploring who the characters are, where they came from, where they’re headed, and the roles they play in the game world.

By then answering these questions, story beats and even entire arcs are much easier to see. And while I’m doing all this, I absolutely flee from the question: "Why would a player want to bang my characters?”

Starting with THAT question only ups the risk of a character feeling two dimensional. Anything that would set up a romantic interest as a plot device or reward, rather than a wholly-realized individual with agency, needs to be avoided like dang proximity mines in GoldenEye 007.

I also remind myself that I don't have to like my own characters. More than one player (hopefully) will be playing whatever my game ends up being. I’ll have at least three. Those three players also aren’t going to like everyone they can ultimately romance. And that’s great, so long as they find at least one character they think is worth getting to know.

If I can write characters who don’t even hint at a potential romance and some players end up crushing on them all the same, I know I’ve done something right. Only then will I add the mushy stuff.

I’ve used this approach even when writing a dating sim. Speed Dating for Ghosts is set in the afterlife. The ghosts in the game exist because they have unfinished business, something common in ghost stories. Most are not conventionally attractive. Some don’t even resemble humans. They’re spirits of mischief, compassion, and despair…spectral weirdos with all sorts of issues to work through and tales to tell. They have goals. They have regrets.

And when I sit the player down opposite them for a couple rounds of speed dating, they have plenty to talk about. Because really, what’s more romantic than flirting with a spirit of vengeance named Gary while helping him solve his own murder?

Ed Sibley (miniLAW, Love Island)

We're used to thinking about game design in terms of the player's agency, and most game designs start by identifying the kinds of interactions a player can have with world. The world of most games is a reactive one - static until the player arrives and starts flipping over tables and kissing everyone.

This is a problem if you’re trying to represent romantic relationships because romance involves the agency of two people, not one. In reality, potential romantic partners aren’t just sitting around waiting for you to arrive. In relationships, both parties must make tough decisions. This is why it's so impactful when Tali’Zorah takes off her mask in Mass Effect 3. This isn’t something the player has asked her to do - it’s a decision that she’s made of her own volition, despite the fact that it will make her fall ill after your night together. The gesture is touching because she’s making a sacrifice to be with you, but also because she’s exercised her own agency to make that sacrifice.

This is where a lot of the drama of real relationships comes from - commiting to someone is a gamble, a leap of faith. Both parties are vulnerable when they make themselves open to each other. Games that portray romantic relationships effectively find ways to foreground this. They must find narrative (and mechanical, ideally) ways to embody uncertainty, nervousness, the tangible threat of rejection. Romance is a two way street, and it’s only convincing when you feel as though the other party has exercised their agency in picking you.

Jared Rosen (The Tingler, Dream Daddy)

HOW TO APPROACH WRITING ROMANCE WHEN YOUR SEXY EVIL PRIEST IS SUPPOSED TO KILL EVERYBODY

If we're being honest, this writeup has been a long time coming. With that in mind let me get the first part out of the way, and MAJOR SPOILERS if you have not played Dream Daddy and then spent sixteen hours scouring the internet for the draft script and junk files containing an ending that never actually shipped: No, canonically Joseph of Dream Daddy is not the leader of a Philistine death cult. He doesn't murder spouses or collect negative emotional energy to raise the the apocryphal sea god Dagon from the bottom of the ocean. He's not a cryptid. Or maybe he is, I don't know. I haven't really talked with the team since ship, and don't own any of that stuff regardless. Nowadays I write about leagues and legends and a space murderer who murders you.

You know, normal games stuff.

Lost in the shuffle, of course, is how to write a convincing romance about a supposedly-evil-sea-priest and an everyman quasi-hipster player dad. Not exactly a common narrative project, but I recently played a game where I romanced a horse with a human head -- so we're all riding hard in the year of our lord 2018.

Approaching it was easy enough to begin with, as I write a lot of LGBTQ-themed horror for magazines. The trick was making Joseph's occasionally odd behavior seem believable in a world where you can date a guy who has extremely strong negative opinions about the mothman. Essentially you're humanizing a monster, but approaching it in a very endearing way that would make a player overlook small red flags -- or dissuade them from breaking into the code/looking up a playthrough video out of suspicion.

I had a couple options. The first was painting Joseph as a not-so-closeted bisexual man. The second was seizing on the near-universal fear of being trapped in a loveless marriage, sequestered away from the life you wanted to live out of some deeper commitment to family and god.

I chose both.

Throw in a verbally abusive wife, suspicious former lover, and four (originally five) nightmarish hell children who at one point in early development were supposed to transform into literal eldritch horrors and... boom. The recipe is there. Now all you need to do is find your execution.

As it turns out, I was once a not-so-closeted bisexual man (now openly bisexual man), hailing from a very strict family in a very small city where being gay was tantamount to throwing a child in front of a street mapping car. I know what it's like to not be able to kiss boys and feel trapped in situations that don't feel like they're really you -- sort of like you're stuck in a small, nicely decorated cell, and can see the life you want to live passing just outside the window. Having spent a good chunk of my childhood listening to my dad talk about "touring with Metallica" (he toured with Metallica), I also had a good sense of what an older Joseph would feel like once he popped out a quartet of children and his life stopped being an adventure.

Suddenly you, a strange dad in a strange but not in any way paranormal town, show up and are met by this handsome, stoic, somewhat reserved father trapped in the tattered painting world of a life he believed he wanted. He can't even do gay stuff! Gotta emancipate him from his marriage. With your mouth. I mean, come on.

Joseph was written believably sad and gay, of course, because in the original script he was tricking you and everyone else in town. In the unreleased final draft of the secret ending he would break the fourth wall, speaking directly to the player as a fellow 'vessel in a dad's body controlled by a third dimensional outside party,' imply he was often pretending to be Amanda, explain why every guy in town but himself was miraculously single, and throw the entire canon of the game (as well as all your decisions) up in the air until he was defeated by the weight of his own stereotypes and you were saved by the (drumroll) strength of the gay community. And also his wife stabbed him. That was Leighton's idea. It was awesome.

But that never happened. Now he's just weird. And sometimes people reference a death cult. Small towns, am I right?

In the end, I guess, I'd say your goal when writing romance is to seize on the humanity of the characters. They aren't just props, because in an age of online engagement your players are going to want way more than a random jpeg of their otome dreamboat redrawn with three different sweaters. They need the world of the game to breathe, and to be interconnected in a way that dating games haven't traditionally been known for. Your dates can't exist in a vacuum any more than a real world romance can -- which is why Joseph had to work even without the horror elements being present.

That's the ultimate goal of a good horror story anyway. Even when you take the monster out, it still feels scary. And you can kiss it on a boat. And it leaves you for its wife.

Fucking dad games.

Subscribe for more interviews at gregbuchanan.co.uk/newsletter - hope you enjoyed!

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like