Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Looking for an idea for a game? Why not try taking a peek at some old ones? Gamasutra looks at five not-quite-classics that had interesting ideas mucked up by poor execution, and uncovers how they just might work as present day indies.

[Looking for an idea for a game? Why not try taking a peek at some old ones? Gamasutra looks at five not-quite-classics that had interesting ideas mucked up by poor execution, and uncovers how they just might work as present day indies.]

A great idea can have a lot of power, but the proof lies in the execution. There's no denying that, in a creative medium like game development, execution has humongous importance. Unfortunately, a lot can get in the way -- budgets, misapplication of concepts that are otherwise solid, or bad features getting in the way of good. In short, concepts are misused.

The best indie games show that great ideas do have power when aptly applied. And many of the best are inspired by game ideas from the golden age, where simplicity was a necessity; these add just enough modern touches to appeal to a lot of different people.

Yet as much as some indie games are celebrated as a melding of the past and the future, there are several ideas from the past that have slipped through the cracks. They've been around for quite a while, of course, and are arguably as unique as some of the best stuff that's come from the last few years, but the games' reputations precede them.

The following feature takes a look at five games from the NES era -- specifically Japanese games from the mid-'80s, when the Famicom reigned supreme. These games are not classics and did not sell millions of copies. In fact, they aren't even recognizable to most people.

If they're known at all, it's because hardcore fans of retro games the world over have turned these games into laughing stocks. They were made on the cheap, by designers and programmers who were probably just punching the clock -- and if not that, then their passion was misdirected. These are classics for different reasons: chiefly the fact that they're ironically loved by the generation that first played them.

That said, these games aren't entirely useless. This article is not intended to defend them, however. This is a simple presentation and evaluation of their ideas. Certainly, why bad or just low-quality games are remembered becomes evident when playing them, but we won't be dwelling on that.

Instead, we present these titles so that today's game developers -- of all experience levels -- can extract the designs that powered these bizarre, broken gems, and think of ways to improve on them for use in a fresh title, rather than relying on the obvious classics. From Famicom dud to iPhone hit? Stranger things have happened...

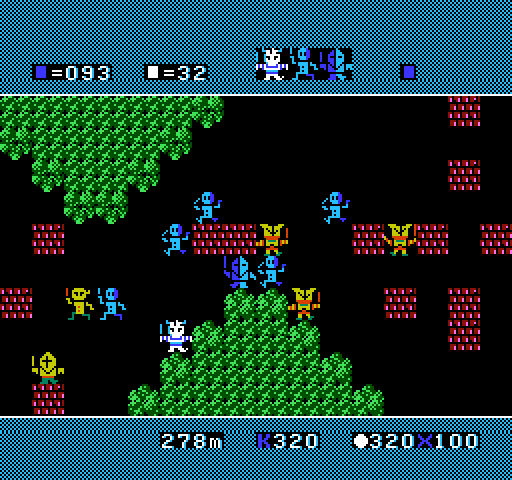

ASCII, 1985

In a Nutshell: A sort of action-RPG where the player amasses a phalanx of troops as they move upon an enemy castle, controlling them all at once. It's a long trek fraught with resistance, though, and battles can destroy you in one swoop if your army's overall strength value is but a digit lower.

Legacy: Bokosuka Wars was ported to Famicom from its original computer version, and games on early PCs were not nearly as deft as the Famicom/NES were, so Bokosuka Wars' extra-primitive graphics and slow scrolling felt out of place on the console, receiving scorn from kids who maybe didn't realize it was from a less-impressive platform. It became one of those aforementioned "ironic" classics some time later.

What to Consider: In the proper time and context, Bokosuka Wars is a clever design, and these days, it is in a sense a bit like a reverse tower defense game, wherein you play the offense; the horde descending upon the stationary castle, and the knights and soldiers you rescue have their separate strengths and can be upgraded.

Taken that way, you have a concept that isn't explored too much in the defense genre. Like tower defense, there is a strategy to it, but not enough to call it a strategy game -- a dependence on simply keeping high numbers of troops can potentially make the game a cinch. Perhaps using less transparent mechanics, and possibly even a more twitch-based element to battles, could keep Bokosuka's concept fresh for today.

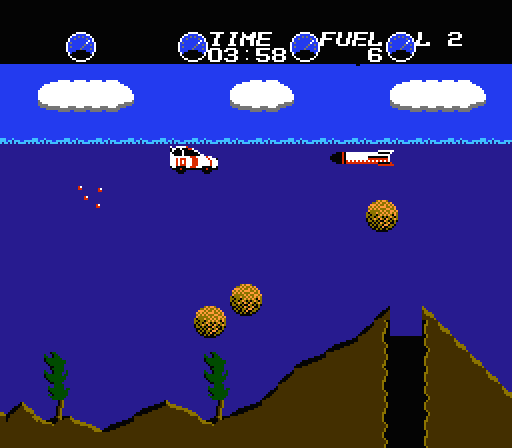

CBS-Sony, 1987

In a Nutshell: A seemingly run-of-the-mill racing game based on the real Paris-Dakar Rally, which includes light adventure elements at the beginning when you have to get a car sponsored before the race.

Legacy: Not much of one. Paris-Dakar Rally is a rickety game, for lack of a better term. The main "race" stages are typical top-down, vertically-scrolling affairs, with track design that never goes any direction but straight, and a tendency to have opposing cars rush up from behind you, frustratingly taking away a try when you least expect it.

But as mentioned, it was only seemingly normal -- as soon as the second stage, the game turns into a platform action game, with your rally car now able to fire small bullets at enemies, and you as the driver able to exit the car and go go exploring to lower a bridge or bypass other obstacles.

On top of that, the next-to-last stage goes back to the top-down view, but now you must avoid a fleet of tanks and fighter jets. A game that looked no-nonsense from the start quickly turns into a farce.

What to Consider: Going against the real world's definition of a car or any vehicle can easily be the core of a unique game concept, and also easily proves the power of a video game’s ability to combine wild imagination with genuine interactivity. Paris-Dakar Rally had contemporaries like Blaster Master, with its jumping-and-shooting four-wheeled tank; that game became a classic.

It can be doubly unique -- okay, ridiculous -- when the vehicle is supposed to be in a realistic situation, like the Paris-Dakar Rally car. A recent example of outside-the-box vehicle use would be Mommy's Best Games' Grapple Buggy, a game that many gamers nearly fall in love with when they hear just the name. In general, a comedic bait-and-switch technique could get some attention, too -- imagine making a Forza-like racing sim where you suddenly go from a tarmac time trial to having to fly a Subaru in an aerial dogfight.

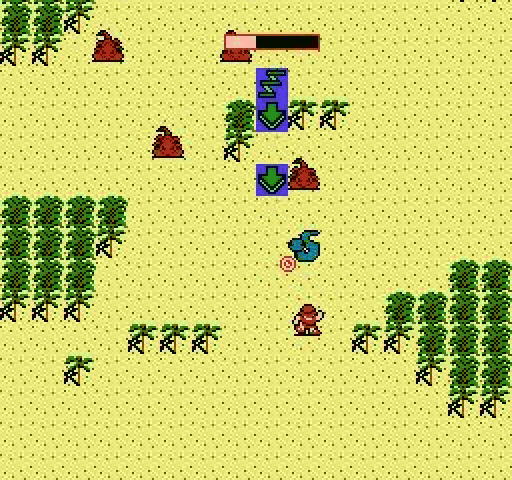

Square, 1986

In a Nutshell: Shoot 'em-up design coupled with a medieval swords-and-sorcery aesthetic. You play as four different warriors, one per stage, and you must keep them alive before they join to face the final boss. When a character dies prematurely, they're gone for good, and the game shifts to the next character, in their own stage.

Legacy: Square published King's Knight some time before the first Final Fantasy, when its track record was not so sterling. The game ended up disliked even today, partly due to its difficulty, but also because of its vague setup: the environment can be destroyed by the player's projectiles, and constantly reveal piles of power-ups that become almost overwhelming and smack of uselessness. Coupled with a need to collect a special item for a character as well as keeping them alive, you got a game that failed to be understood in its time and paid for it.

What to Consider: Most action games feature one hero with multiple lives, but King's Knight's approach isn't used too often. Sure, it's a bit harsh, and anything that takes after it probably doesn't need the player to collect a bunch of items and survive to the very end, but it's an interesting way to deal with failure in games. Life goes on, in other words.

And in a broader view, the arcade shoot-em-up style could always use a fresh concept, even if it's an on-foot, medieval affair where you can chip away at mountains with your magical beams.

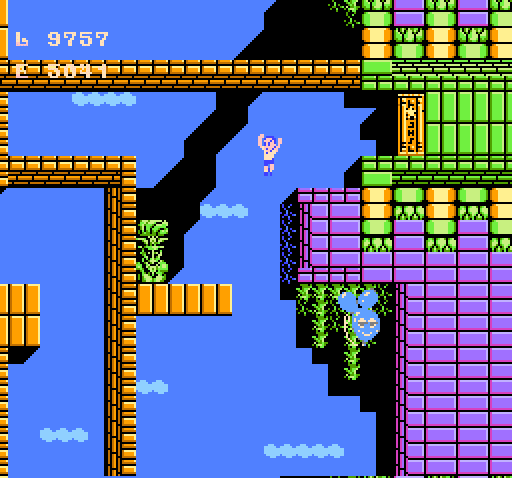

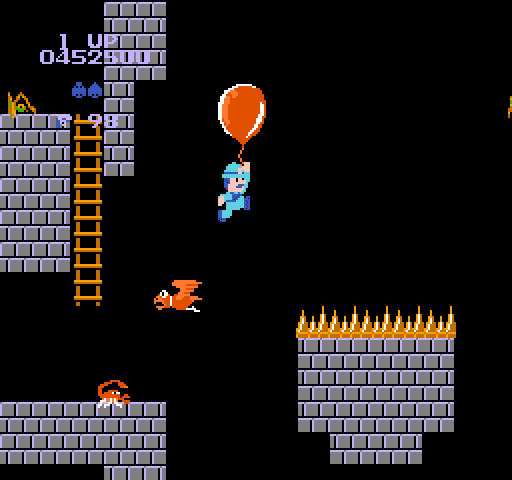

Jaleco, 1986

In a Nutshell: An expanded sequel to the arcade game Psychic 5, Esper Boukentai is a fairly standard platform action game where the player character can make huge jumps several stories tall, which are needed in order to navigate the giant vertically-oriented levels.

Legacy: Besides being of a general low quality, Esper Boukentai was ragged on for being vague and having arbitrarily-placed enemies (from a cast of rogue household appliances), and few clues to tell you where to go, as numerous doors are placed around the game world that hide items needed to continue past level barriers).

Not to mention that the jumping is totally overwrought. It seems completely unnecessary in practice, which is what brings the game down, because it could have been easily done without the crazy jumping or vertical maze-like levels.

What to Consider: "With great power comes great responsibility." These days, games with super-powered characters fall into the category of open-world titles (inFamous; Prototype), but they usually have environments that support them well.

But even if you want to make a 2D linear platformer like Boukentai, crazy abilities can be fun and make an indelible impression as long as the levels are properly designed around them, including a semblance of cohesion, and not the sprawling towers of Boukentai. If you ever used a Game Genie to make Mario "moon jump," you'll already understand.

Pony Canyon, 1987

In a Nutshell: An underground action-adventure that has a very loose link to Activision's series, notably Pitfall II more than its predecessor. Hero Harry must rescue his niece, his feral animal friend, and grab the lustrous Raj Diamond in an underground cavern that approaches the center of the earth.

Legacy: By no means is Super Pitfall good. In fact, it's not unfair to call it one of the worst NES games. The animation is terrible, the physics are terrible, the graphics are more Super Mario Bros. than Pitfall, and it's vague to the point of infuriating -- special items needed to complete the game are invisible, and only able to appear by jumping around where they hide. The open-ended subterranean world is a few degrees more subtle than Metroid, with not as many necessary barriers -- the kind that keep the player on some sort of path to victory.

What to Consider: Or rather, does Super Pitfall even have anything worth considering? Well, nothing too obvious, but there might be something there. By looking at it a little deeper, one can grasp a certain way of designing exploration-heavy games like Super Pitfall.

Without a manual, map, or strategy guide, Super Pitfall becomes a pure trial-and-error expedition of the underground, with a certain (yet low) degree of discovery and magic moments (again, a low degree). With that in mind, one could make a game that jets ahead of Super Pitfall and gets as close to a "sandbox" as possible, with a loose goal that couples true exploration with graphics and physics that are actually good.

The indie game classic Cave Story blows away Super Pitfall, but it still can't escape being compared to Metroid, and part of that comparison is the way it strikes a balance between knowing where to go and still having cool stuff to find -- whether it's a power-up, a funny character, or just a scenic area to admire.

And even though the maps of Super Pitfall's areas are a series of rectangular passageways, unimaginatively designed in some sort of "rack" formation, had it actually possessed some true character, it may not have turned out quite as bad as it did.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like