Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this new feature, two researchers at North Caroline State University share research that's been done on how games improve the lives of players, and chart a path toward game companies conducting their own -- complete with practical suggestions.

July 24, 2012

Author: by Anne McLaughlin

[In this feature written by two researchers from the Gains Through Gaming Lab in the Department of Psychology and North Carolina State University, you'll find "a selective, non-exhaustive review" research on "benefits afforded to cognition by video game playing", as well as practical thoughts on how you can research "the potential benefits of playing your video games."]

Little Timmy age 12 tells his parents he wants a video game that all his friends are playing. So Dad takes him down to the store and finds that the game is rated Teen. Hmm...

Dad is not sure so he reads the back of the game and finds that the ESRB provides content descriptors to go along with the rating. The descriptors for this game include "Blood and Gore, Crude Humor, Mild Language, Suggestive Themes, Use of Alcohol, Violence." That is a long list of pretty negative words, not to mention that the title has the word "war" in it, so Dad decided against buying the game for Timmy. Sorry Timmy.

Perhaps this outcome could have been different. What if that same ESRB label also included all the positive benefits of playing that particular video game or games just like it? For instance, what if the following were added to the label: "Research has shown that playing this game is linked to: improved reading comprehension; leadership skill development; increased social interaction; improved cognitive functioning."

When making decisions, consumers should know the positives as well as the negatives. So why are consumers currently getting just one side of the story? If the positive psychological benefits of playing a particular video game were known they may counterbalance or even outweigh the perceived negative effects conjured up when reading current content descriptors.

It is unlikely the ESRB will change its labeling system, and there are probably legal issues with making strong causal claims, but that does not mean that developers and publishers can't support, conduct, and publicize research that promotes the benefits of playing their video games.

It is the potential psychological benefits attributable to playing video games that are the focus of the following discussion. Specifically, we provide a selective, non-exhaustive review of the research with a particular focus on the benefits afforded to cognition by video game playing. After which, some advice for developers and publishers interested in having research done on their games will be provided.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, as video games became more ubiquitous, the graphics more realistic, and the plots more engaging, psychologists began research to determine if there were negative implications to playing video games such as increased aggression. The relative merits of this research, still a hot area of inquiry, are open for some debate (i.e., since 1996 violent crime rates in the U.S. have declined while the sales of video games has increased). This is not to say that young children should play excessively violent video games; indeed, they probably should also avoid violent movies or TV.

Given all the research on the potential negative effects, in the late '90s a small group of researchers started wondering if video games might have some positive benefits. The results of these early studies by and large confirmed their hypothesis -- playing video games was related to some positive outcomes. The majority of this research has focused on cognitive functioning which makes sense given that many video games require cognitive skills like problem solving, reaction time, memory, spatial ability, and attention to play the game.

A caveat needs to be made before proceeding; this admittedly selective review of the research only focuses on studies examining the impact of commercially available video games. It does not include research on serious games, games designed to "save the world", or "gamification" (perhaps the most overused term in academia, currently).

While the work in these areas is important, and no-doubt beneficial, the resulting games are explicitly developed to produce positive outcomes (e.g., losing weight, learning chemistry). Research showing the benefits of these games is a more a "proof of concept" than anything else. Unfortunately, some of the the developers of these "make life better" games do not scientifically establish the efficacy of their games, but that is a topic for another article. So this article, as well as our own research, is concerned with commercially available video games made for entertainment purposes.

Most of the research examining the positive benefits of playing video games has focused on cognitive functioning, a broad term used to refer to a whole host of specific mental abilities such as memory, processing speed, working memory, spatial ability, attention, and perceptual skills. Each of these cognitive abilities is measured using specific tests, many of which are similar to or the same as measures of intelligence.

The work by Bravier and Green is widely considered the first set of studies examining the relationship between cognition and video games. In a series of studies they compared the cognitive functioning of undergraduates who were habitual video game players (e.g., played action video games four days per week for at least one hour per day over the last six months) to a group of undergraduates that were non-video game players.

The work by Bravier and Green is widely considered the first set of studies examining the relationship between cognition and video games. In a series of studies they compared the cognitive functioning of undergraduates who were habitual video game players (e.g., played action video games four days per week for at least one hour per day over the last six months) to a group of undergraduates that were non-video game players.

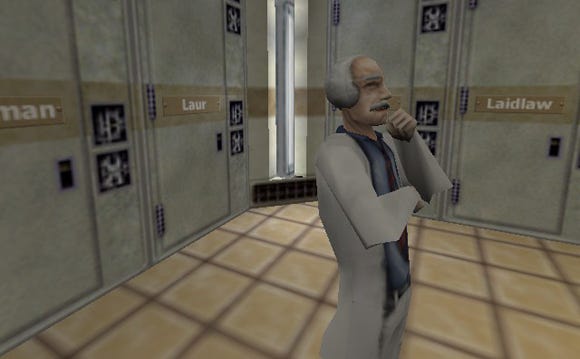

Participants in the habitual video-game group reported playing the following games: Grand Theft Auto III, Half-Life, Counter-Strike, Crazy Taxi, Team Fortress Classic, Spider-Man, Halo, Marvel vs. Capcom, Rainbow Six: Rogue Spear, and Super Mario Kart.

Across the different studies, the authors found that the habitual video game group performed significantly better on tests of visual attention, spatial ability, and visual short-term memory skills compared to the non-video gaming group.

The video game-cognition relationship is even found in participants who you don't think of when the word "video game" is used. In a study of over 150 adults over the age of 65 conducted in our lab we found that almost half our sample played video games at least once a month. Those "gaming grannies" performed significantly better than non-gaming older adults on a wide range of cognitive abilities including memory, reaction time, and spatial ability. In fact, they even performed better on measures designed to assess their real-world memory ability.

By and large the preponderance of the evidence suggests that individuals who play video games perform better on measures of cognitive functioning than individuals who do not play video games. Our work is not alone; other studies have found that older adults who play video games have, on average, better cognitive functioning than those older adults who do not.

You don't need a doctorate in psychology, or even an undergraduate degree, to realize that these findings can't tell us anything about causality. As with any activity that is cognitively challenging, people who enjoy or need that challenge gravitate to toward something like games. It, of course, is possible that people with higher cognitive functioning to begin with are more likely to play video games, rather than playing video games causing better cognition.

Consequently, to test causality, experimental designs have been utilized where participants are assessed at a baseline (pretest) then assigned to a control group or a group that plays a video game for a set number of hours over a set number of days. After the training is over, all participants return for a posttest, and the changes in performance are compared between the groups. These experimental design studies are also referred to as intervention or training studies, since their goal is to improve (intervene) in cognitive functioning, and playing video games is considered a form of training.

Green and Bavilier used an experimental design where participants with little or no video game playing experience were assigned to a control group that played Tetris or to a group that played Medal of Honor: Allied Assault. Both groups played the game they were assigned to for one hour a day for 10 consecutive days.

The Medal of Honor group had significantly greater pretest to posttest improvement on measures of visual attention then then Tetris control group. These results have been replicated in other studies also using Medal of Honor as well as Unreal Tournament 2004. In fact, in one study, pre-existing gender differences in spatial ability -- females performed more poorly than males -- were eliminated after 10 hours of playing an FPS.

In our research lab, we examined whether playing World of Warcraft provided any benefits to the cognitive functioning of adults over the age of 65. We assigned 20 participants to a control group, and another 17 to the experimental group, who were given a copy of WoW and told to play for at least 14 hours over the next two weeks. We found that, over the two weeks, participants averaged 15 hours of playtime, reached level 11, and completed 14 quests.

We examined cognitive improvement in the WoW group based on their baseline performance; participants who were performing poorly at baseline showed significant improvements in attention and spatial ability that were not seen in the control group.

In another study, older adults played Rise of Nations for 23.5 hours over a four to five week period. Relative to the control group, participants who played Rise of Nations exhibited substantial gains on a number of different measures of cognition including task inductive reasoning and short-term and working memory.

The above studies have also found evidence that the cognitive benefits due to video game playing transferred to real-world skills. For example, a recent study assigned medical students to one of three groups: a control group who were told to refrain from playing video games, a 3D gaming group that played Half-Life, or a 2D group that played Chessmaster.

The students completed a pretest which included a virtual reality test of their surgical skills, which relied upon abilities such as spatial ability, mental rotation, and reaction time. The two gaming groups played 30 to 60 minutes each day, five days a week, for five weeks -- after which they returned and took the tests again.

The students that played Half-Life performed significantly better on the tests of surgical skills than the other two groups. Similarly, a study found that laparoscopic surgeons that played video games were 27 percent faster and made 37 percent fewer surgical errors. In fact, surgical experience and years of practice were not as good as prior video game playing experience in predicting surgical skills.

Constance Steinkuehler and her colleagues have long argued that playing video games, specifically MMOs, leads to higher levels of literacy and written discourse in adolescents. Recently, they found that when high school MMO players were given a choice, they most frequently elected to read informational text related to gaming.

On average, these sources were written at a 12th grade reading level, and 20 percent of the vocabulary in the text was academic, while only 4 percent of the text was gamer slang. Furthermore, kids who were supposedly "struggling readers" actually performed with 94 to 97 percent accuracy on gaming related texts which were seven to eight grades above their so-called "academically defined literacy level." These findings suggest kids who play video games engage in intellectually stimulating activities (i.e., reading) outside but associated with gaming and their literacy level may be actually much higher than what is assessed by academic tests.

If you are a developer or publisher and the idea of doing research on the potential benefits of playing your video games sounds interesting, you have two options. The first option is a partner with an academic researcher for evaluative studies. The second option is to do the research yourselves.

Both of these approaches have pros and cons that should be considered. One pro of collaborating with an academic is the potential to get the research done for relatively cheap. Academics are like MacGyver -- when it comes to having no resources to do research. Providing copies of the game, maybe some hardware, and the salary of a graduate student will go a long way.

One of the drawbacks will be time. Quality research takes time (and intervention research takes even more time). Second, universities charge what is in essence a tax on any money awarded to the university for research.

This tax is called Facilities and Administration costs, or F&A, and it covers the costs incurred by the university in the pursuit of research related to facilities (e.g., utilities, depreciation on buildings, depreciation on capital equipment, maintenance and repair, and libraries) and administrative components (e.g., HR, payroll, research administration office).

The F&A rate varies by institution, but one common rate is 49 percent; so if a researcher needs a $100,000 for a study, it will actually cost you $149,000. That extra $49,000 is the price of doing research with a university. This still might be pretty cheap, considering the costs of hiring someone and performing the work in-house.

Another benefit of collaborating with an academic is the objectivity he/she brings to the research design, data analysis, and interpretation. There might be some level of skepticism if a developer releases the results of an in-house study suggesting that that its zombie killing game improves thinking speed. But if this developer partnered with an academic, much like a pharmaceutical company partners with contract research organization for drug testing, then there is a level of detachment from the product which alleviates some concerns about objectivity.

Doing the research in-house is a good option, particularly if you want to have total control over the research questions. Academics do not understand what ROI means, so the research questions they want to ask may not exactly match up with your bottom line. In addition, if conducted in-house, then you have and ownership and control of the data. Academics need to publish the findings of their studies regardless if they are positive, negative, or mixed. What could potentially be reported or how it is reported might not match up with your business model. Consequently, having control of the data might be important.

Of course the downside of doing things in-house is hiring someone who can actually do the research. Companies like Valve, Bungie, and Microsoft have done an excellent job attracting talented researchers with PhDs in psychology and related fields. However, it can be difficult taking someone trained as an academic and placing them in a business setting, where research is done not purely for the pursuit of knowledge.

Alternatively, taking someone who has business experience but little research experience could have disastrous effects -- you need more than a marketing degree to conduct sound research. If the goal is to conduct theoretically and empirically sound research to answer questions that have business value, then your first concern is to hire individuals with the formal training and the experience to conduct the research. Your second concern is helping them develop an understanding of how the research can and will be used to increase the profitability of the company. Given the state of academic job market, finding someone with the qualifications might not be too hard.

Ultimately, you can't lose either way you go. We would suggest that if you are not currently doing research but want to, then partnering with an academic is a good idea. This is a low-commitment option and allows you to get your company's feet wet with science. If you are already doing some research, or sold on the idea and want to start in a big way, then hiring a PhD trained researcher is the approach we would suggest.

Cereal companies have it right. They are required to have a nutrition label that shows EXACTLY how much sugar, calories, fat is in each serving, and if it is a cereal that tastes good, one or all of these values will be high. However, on the same box, they might also tout "Great Source of Fiber!" or "Kids that eat breakfast do better at school!"

Video game companies are required to have "nutrition labels" too, but they fail at pointing out the positives (besides the fact that you can kill zombies). We would love to see on the cover of our next video game purchases, "Has been shown to improve thinking speed!"

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like