Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

How going "old-school" with game saves -- they're manual! -- created a sorely-needed sense of tension in Creative Assembly's first-person horror-shooter Alien: Isolation.

Game Design Deep Dive is an ongoing Gamasutra series with the goal of shedding light on specific design features or mechanics within a video game, in order to show how seemingly simple, fundamental design decisions aren't really that simple at all.

Check out earlier installments on the unique touchscreen control of Helix and on the plant-growing mechanics of Grow Home.

Also don't miss these developer-minded looks at the tutorial system in Rogue Legacy and Amnesia's sanity meter from our ever-growing Deep Dive archive.

I am a game designer with 14 years industry experience and lead positions on many triple-A titles, on a wide variety of genres including third person action adventure games, film licenses, racing games, first person shooters, platformers and simulation games. Most recently I was the lead designer on Alien: Isolation, which released October of last year and is still scaring people, according to my Twitter feed.

I have often answered questions on the game’s systems, the choice of crafting approach, the level design and of course, the alien itself. Of all the systems, AI entities, mechanics and designs that have made Alien: Isolation such an immersive game, one mechanic often causes a big reaction from people, and as mundane as it sounds, it is the save system.

Who would have thought that such a choice would trigger such passionate reactions from players around the world? It turns out, if you get even a simple mechanic right, you can trigger exactly that. The save system in Alien: Isolation took a rather drastic and some would say “old school” approach to saving. We have no “soft saves” or checkpoints in the game. The only way of saving is to locate a terminal in the world, put in your access card, wait for the systems in the fictional machine to warm up,� and then wait for the three simple lights to blink off -- all the while knowing that you could be killed at any moment.

When we first approached the save system we had the usual checkpoints and menu-based saves. We looked at the games we were all playing, and spent some time balancing when these saves occur and how often.

Like any development team, we all play a lot of games and each have our favorites. Often our decisions and choices are colored by the games we play and our own personal preferences. On this occasion, I was set on using a checkpoint system with hard saves every now and then. For me, it worked in games like the Dead Space series, Metroid games and BioShock, and was a simple system to understand.

However, sometimes “simple to understand” is not the right approach when you are making a game that is designed from its core to terrify and put people on edge.

One of my favorite game mechanics of all-time is the active reload system from Gears of War. I was fortunate enough to meet its inventor, one Clifford Michael Bleszinski, at an EA event we were both working at a few years back. I asked him if he had invented it, and he confirmed it was him -- and he added how surprised he was that other games hadn’t copied it more. After a good chat where we went through games that could have used it, we went our separate ways.

The reason I like this mechanic so much is that it added a huge level of emotion to a previously simple interaction. Pressing X to reload was a staple of many games. It became an annoyance rather than an interaction, in some cases. The most emotional thing you could get from it was "dead man’s click" -- aim, fire, and then nothing, aside from the realization that you have an empty clip.

With the active reload system, if you perfected the timing, you did more damage and got a faster reload. “Damn, I'm good!” you would think as a satisfying glow appeared on your ammo and you were able to start mowing down the Locust quicker. The flipside is the feeling of dread as you messed it up: A jammed weapon, a longer reload, a lost chance at bonus damage. It was risk vs. reward in the simplest form and it worked a treat.

The question I found myself asking was, "Could a simple interaction like saving trigger such emotion?"

Now, I would love to say that it was all my idea, and that this was the plan all along, but alas it was not. During development, one of our designers (now a senior) by the name of Simon Adams came to me with a pitch for a manual save system. I said no many times -- "what we have is fine." It seemed to me like too much change, or hassle, and a lot of work on the game environment: We would have to place terminals everywhere, change the art for the affected areas, and change the code for the save system.

Then there was the alien. For those who haven’t played the game or don’t already know, our alien is systematic. It is an AI entity that works under its own logic, hunting for signs of the player, other humans on board, and anything it can kill. It adapts to the player’s movement, choices, weapons, and makes some interesting design possible.

It was the question of what to do with the alien when we save that raised the debate of save points again. "When I get to a soft checkpoint and the alien is about to kill me... What happens when I come back in? Is he still there?"

We had two clear options. One option meant not doing anything which would trigger an infinite loop of dying and respawning. The other option was to remove the alien on the load, which would mean sprinting to a checkpoint was a valid tactic -- as after he killed the player, they were safe again. Neither of these were good enough, and neither supported the core gameplay.

Simon again pitched his manual save idea, this time as a solution to our issues. If we could have a save location, we could either alter the alien’s behavior in some way so that it could adapt to save points or leave it up to the player to ensure that they were safe when saving.

We decided to test the latter in a simple quick-and-dirty prototype. Our design team quickly put together a simple scripted push-button save point that would trigger a manual save. The first mission to use this suddenly took on a different feel. No longer were we walking around, without a care, knowing that if we died, we wouldn’t lose much progress. We were afraid. If we didn’t make it to the save point and successfully save, we would lose our progress. Even in a single mission this was tense.

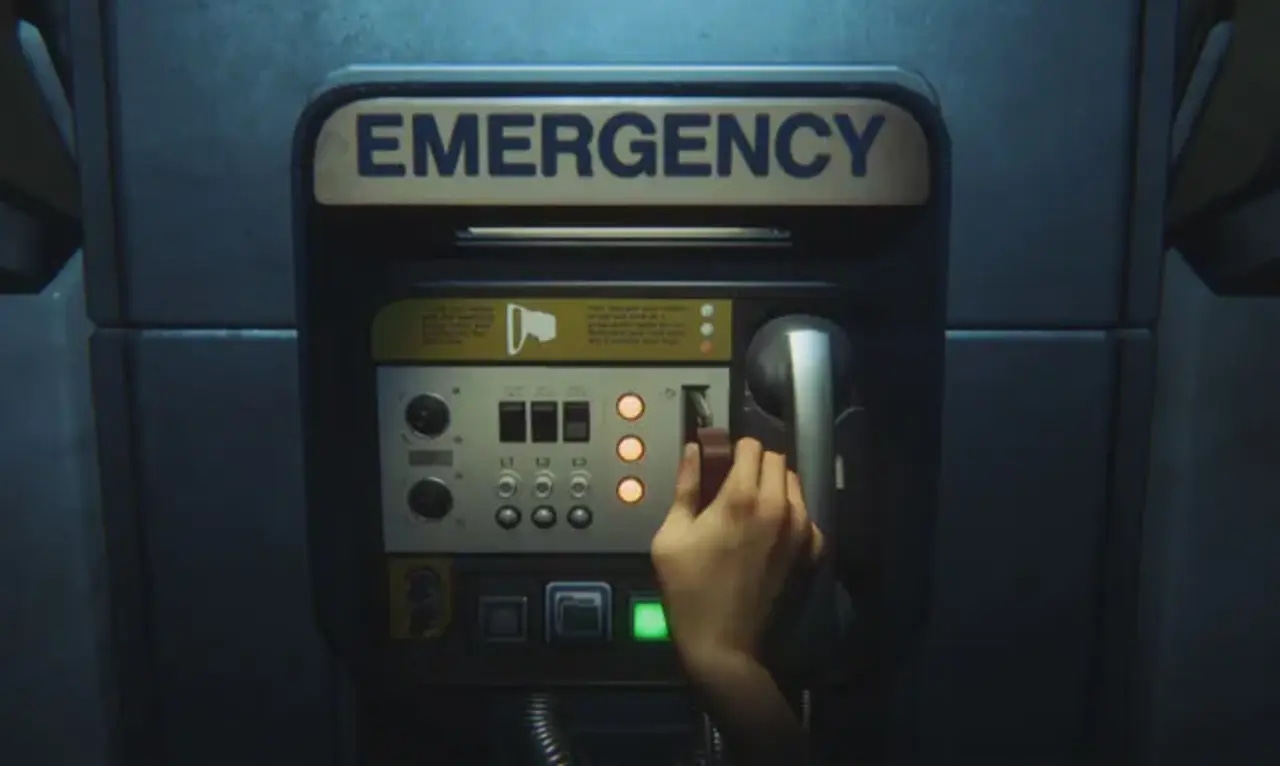

"Imagine if you had been playing for a while and not saved? How tense would that be?" This is where the emotion started to appear. Saving became tense. Looking for a save became tense. Imagine that! The simple act of saving had become supportive to the game's driving factors of terror and isolation. A further modifier to this was a simple tweak that Simon made to the prototype save point. He changed the model that was used from a push-button to the card terminal used in other interactions in the game. This interaction was taken directly from the original film, where Dallas uses a form of key-card to access Mother, as seen below:

Simon made a change to this interaction and used our game's scripting tools to pause the animation for a time whilst three beeps triggered. This small change made a huge difference on the mechanic and in many ways, sold it to the non-believers and checkpoint-savers.

Seeing players bouncing their knees and talking out loud whilst a save point triggered, saying things like "Come on! He's nearby!" was amazing. Another emotion was also present that was unexpected: relief. Players were relieved when they successfully used a save point, and also upon seeing one. The sense of excitement at finding a save point became a highlight on the path through a level, and one that sometimes caused players to dash to use it -- even when it wasn't safe.

For me, this became a clear evolution of our save system, and one that benefitted the game as a whole. Players would risk further and further stretches of gameplay between save points, knowing all the time that they would need to save soon or risk losing their progress.

A tangible sense of loss came when this risk did not pay off and, although some have called it "punishing," it fits with the style of the game and its main enemy. We tried to design a game where when the player was killed, they knew it was something they had done -- or failed to do. A player only needs to have that sense of loss once from losing progress to feel the tension and stress of looking for a save point in the dark, with an alien hunting them.

Whilst I would love to take the credit for this idea, the originator was Simon Adams, and it was a team effort to implement the art, animation, code, audio and level design. The game was changed forever by its use. I am glad I listened to Simon... eventually.

This article was first published February 10, 2015 and has been updated in 2024 for formatting.

You May Also Like