Game Design Deep Dive: Creating an adaptive narrative in Reigns

"As soon as we weighted the decisions of the player with consequences on the 4 dimensions of power, we gave a lot of meaning to very simple swiping gestures." says François Alliot, creator of Reigns

Game Design Deep Dive is an ongoing Gamasutra series with the goal of shedding light on specific design features or mechanics within a video game, in order to show how seemingly simple, fundamental design decisions aren't really that simple at all.

Check out earlier installments, including the action-based RPG battles in Undertale, using a real human skull for the audio of Inside, and the realistic chat system of Mr. Robot:1.51exfiltrati0n.

Who: François Alliot - game dev for Nerial.

I am an independent game designer and game developer. I developed and wrote Reigns, the swipe your own adventure game published by Devolver Digital. I started making games 3 years ago, this is my second professional life.

What: Writing a narrative with probabilities

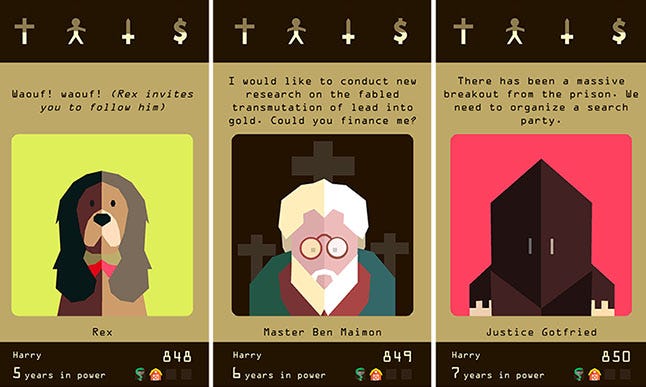

The first thing decided with Mieko, the artist of Reigns, was the game’s core mechanic: use a swiping interaction (very much like Tinder) to play a King taking binary decisions about his Kingdom, through a deck of cards representing your different advisors.

Each of your decisions has impacts on your Kingdom and your objective is to stay on the throne as long as possible. Things generally go awry pretty quickly and you end up dying in gruesome and colorful ways.

Initially, Reigns was very much like a very lean management sim: you had to balance the 4 pillars of your power (church, people, army and money) and the questions asked by the advisors were randomly selected.

That initial mechanic worked very well on an emotional and physical level. Like Tinder, it’s a toy (as a very smart person told me one day), but a toy with surprising depth. As soon as we weighted the decisions of the player with consequences on the 4 dimensions of power, we gave a lot of meaning to very simple swiping gestures.

That was fun for 10 minutes. And that, believe me, was a great start. We just needed to hook the players for the following 2 hours.

We discovered that the players were very quickly making up stories with the bundle of 50 cards we initially had in the game. They were creating meaning between events that I didn’t actually link in the game like a famine and a wedding proposal.

We decided to build upon this, enrich the stories the players were creating by challenging their expectations within these first 10 minutes.

Why: oh why?

To do this, we turned the random selection of cards into a probabilistic system. That’s a rather complex expression for something that’s actually quite simple that I will try to explain here.

Imagine a bag with the interesting ability to expand and shrink in order to fit the contents you put in it. By default, that bag contains all the cards available in the game. When I’m about to select the next card shown to the player, I start by removing from the bag every card that doesn’t fit the state of the Kingdom.

I have many variations of this, but for example, if a range of cards are related to the presence of a queen but you’re not married yet, I remove those. If a card is only triggered if the church is strong but you have a weak church, I remove it too. I also remove all the cards that have been played too recently.

This creates a bag of cards that’s very different each time each time the player is about to see a new card. The final touch is to associate every remaining card in the bag with a size. The « larger » the card, the more space it will occupy in the bag.

You end up with a bag of mixed cards, large ones that take a lot of space and smaller ones. I then select one card randomly from the bag and display it to the player.

The fact that some cards are larger than others creates interesting possibilities. The probability a larger card ends up being the one that is selected is greater than the probability of a smaller one. But if the larger cards are not in the bag because they have been removed at the previous step, the overall probability of the smaller cards to be picked up increase a lot.

That’s why the ability of the bag to shrink and expand is important. If you start a war with your neighbor, the 10 or so cards related to that specific event are large and will take a lot of space in the bag, more than cards not associated with any particular condition, like the jester cards. That maximizes the probability to pick a war card during the reigns where you suffer the war and minimizes the probability to pick a jester card.

Once the war is over, the war cards are removed from the bag so the system has a lot more chance to select jester cards again because their probability to be picked up increases.

Some events, like the dungeon or the duels will lock the game in a smaller sub-system, where the bag will be very small, containing just a couple of cards. This sub-system could also just be a single card, creating linear paths (like the devil’s encounters).

The versatility of that probabilistic system was essential to build the game. I really considered it as a tool or a grammar to push the game in wacky and unexpected ways rather than a closed system that needed a defined amount of content to be “perfect”.

I don’t mind Reigns' imperfections, they’re essential to the game and its weird tone. We were always careful to build everything around the core gameplay loop, the “playfulness” and the tone of the game, but we didn’t put any specific limit to the number of things we wanted to put in the game to surprise our players (and mess with them a bit).

Writing Reigns was really a process similar to an exploration. You pack your things as tightly as possible and hope for the best. I started by writing regular “one-shot” cards, then I tried range of cards to build mini-storylines triggered over a short period of times, then add-ons, like new characters and events permanently adding new cards to the deck, then the devil’s storyline, and a lot of wandering around the core gameplay designed to bring the player in unexpected places and situations.

For example (spoilers), there's running blind in a forest, picking magic mushrooms, deciphering your advisor's question when plagued with old age, dealing with the infernal money of slavery, gambling with the Jester, being “apparently” in love, entering the “pungeon”, dating a pigeon…

Conclusion

Through this system, we managed to intertwine narratives with unexpected depth, between very broad thematic cards, subsets of storylines around specific events developed in some Reigns but not others and a hidden meta-game triggered over centuries.

In that, Reigns is following (very humbly and scantily) the quality-based narrative approach mastered by Failbetter Games. Our qualities are what I call the global game state against which the bag of available cards is recompiled every time the player swipes.

In the end, the core loop, the Reign, mixes a new selection of cards each time, ranging from purely random choice to very authored paths triggered by previous choices. This mix has a very interesting consequence. As soon as the player discovers that some cards take into account his or her previous choices, potentially every card becomes meaningful, because it’s very difficult to discern the more randomly picked cards from the authored one.

Even with a minority of cards taking into account your previous choices, the whole game becomes authored in weird and unexpected ways, encouraging the players to make up their own stories. Who is to say that the discovery of the blue mushroom is not a consequence of recruiting the witch? Or maybe is it a consequence of the plague?

I couldn’t say.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)