Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Are the many attempts to come up with new, fresh theories of fun beside the point? Should designers stop trying to analyze what fun is and instead read what's already been published and then work on new games? That -- and more -- is what DigiPen professor Neils Clark argues in this new piece.

In the two weeks before writing this piece, I've seen easily a dozen scattered, derivative definitions of fun. Five page "manifestos" and weird Rubik's Cube personal philosophies. No respite at DigiPen the other day. Covering for another prof, I thought I'd poison the youth with design theory.

"Oh, sweet," says one edgy-looking student. "Me and a buddy have been talking about making a unified theory of fun. An exhaustive language for games."

"Neat," I say. "Have you read Raph's Theory of Fun?"

I click to the first slide, a cropped image of the cover.

"Uhh, Raph?"

"Ian Bogost's Persuasive Games?"

"I stared at the first page for awhile."

"Good enough." I say, though it really isn't. I want the laughter, but they only give me puzzled stares.

Fun is a lazy word. A bit like "game". On first blush anyone can grin, nod their head, and think they understand what you're talking about -- but there are breathtaking gulfs between Today I Die and World of Warcraft, between Monopoly and Foursquare (both social networking or playground variants). Pete Garcin wrote a good piece last year about the problems of broad language, though he wasn't looking to, "pick on 'fun' specifically."

Let's pick on fun, specifically.

Fun is a process. Idea to shipped game is roughly the difference between a frozen ovary and a 24-year-old human. Things happen in between. Fun may or may not be one of those things. Maturity may or may not be one of those things.

Fun is a process. Idea to shipped game is roughly the difference between a frozen ovary and a 24-year-old human. Things happen in between. Fun may or may not be one of those things. Maturity may or may not be one of those things.

Testing early and often doesn't just work out bugs. The creators start to see what, in this growing new reality, is enjoyable. The social element? Running? Painting? Climbing? Problem solving? We hope that by the time it ships, this little life is, at the very least, functional.

That fun process sometimes gets a few tries. Super Mario 3D Land Director Koichi Hayashida recently said that even across Nintendo's games, they've added to the pot, taken some away, and considered what elements to keep and why.

Hayashida said, "What you have to do is make an investigation at every new stage and say, 'Okay, which of these elements is working well for us, and which of them do we need to think about minimizing, or removing entirely?'" He's trying on these mechanics, but all that talk requires crunch and craft to mature. Within the process, or even between projects, there isn't much time for talk. Studying new and glorious descriptions of fun is laudable, but not exactly a priority.

We already have a vocabulary. We use games to talk about games, especially where those are emblematic of a certain type of experience. That's the lingua franca. Like certain words in Sanskrit poems, which translate to pages of English description, naming certain games condenses hours of detailed, unique memories.

I recently overheard during a games critique: "Ditch the broken Portal puzzles and stick with your 3D VVVVVV mechanics" among dozens of constructive quips that spoke in the shorthand on tap: our mosaic cant of games. All calling to mind experiences we've got in common, before said team hunkered down for the long, hemorrhoid-inducing crunch to include two, maybe three of the dozens of suggestions floated.

Cliff Bleszinski was on fire with these ludic linguistics in this interview with Brandon Sheffield. Easily a dozen quips like, "I would've loved it in Skyrim if my fiancee could have left a treasure in a chest in my house while she was playing, Animal Crossing-style. You know, Fable with the orbs in the world, that's where we're all going, right?"

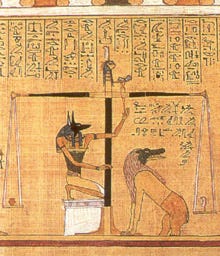

That sentence is going to mean fuck-all to a lot of gamers, let alone shambling great-grandmas (he's talking about this). To the right audience, there's a depth of meaning. But that language of games isn't the same as an elastic alphabet. It's a rough-hewn, hodgepodge collection of hieroglyphs. Finished, well-peddled games form the brunt of our symbolic language. And the effort required even to copy known hieroglyphic passages is staggering. Equivalent to carving into solid stone, with tools that'll seem antiquated and ball-busting in a generation or two.

Graduating from referential hieroglyphs to a specific alphabet might be a seductive adventure for some, but a unified language is a major undertaking. Beyond the question of whether anyone would give a shit (we have, after all, spent thousands of hours learning our various shorthands) well... whose work -- of the dozens (probably hundreds) of academics and devs who've contributed -- do you favor?

Ernest Adams, Richard Bartle, Jesper Juul, Nick Yee, Steve Swink, Janet Murray, Koster, Bogost, McGonigal, Hunicke, Brathwaite, Schell, etc, etc? Some of them conflict, sometimes clearly and vocally, sometimes subtly and in back channels. An uncareful vocabulary might suddenly get political. Maybe that invites a counter-vocabulary, and then the whole point of the exercise is gone, lost in translation.

Let's say you're undaunted. Neat (the experiment is underway anyway). The very first thing to do, before committing your views, prognostications, and formulas on "fun" to print, is to read Raph Koster's A Theory of Fun for Game Design. Seriously. It costs 15 dollars, most days, on Amazon. That's 20 bucks, with shipping. You can afford that, if only to keep ten thousand game developers from crying out in terror, then suddenly closing their browsers. It's an easy book that mixes lay psychology with this curious craft (and the comics are adorable).

Pulling on some of Nicole Lazzaro's research, Raph expands our vocabulary past fun. For instance, Lazzaro is credited with highlighting cross-cultural terms for social engagement. Shadenfreude, the unpronounceable German word for the glee of watching other people fail. Fiero, a fiery expression of achievement. Kvell comes from bragging about a person you mentor, and Naches is the pride of their success.

There are others. Lazzaro herself gets in-depth with a language of fun (easy fun, hard fun, serious fun, people fun, how we swap between -- I'll let her introduce herself in the video link above). Raph takes a wide swath of fun, for designers and players, psychologically and biologically.

Spoiler alert! Raph calls the highest form of fun Delight -- the learning that comes from matching new patterns, and improving ourselves in the most basic of ways. That learning is deeply rooted in our physiology, in human evolution, and "the only real difference between games and reality is that the stakes are lower with games."

It hearkens to that old axiom: easy to learn, hard to master. The book spawned the popularity of some of the most delicious ideas in game design today. If you love games, then you're doing yourself a disservice by avoiding Theory of Fun.

Flow is oft-brandished by theoretical fun seekers. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, or even the easily-read Finding Flow, are primary sources here. If you're not into that, Gamasutra has one or two pieces on Flow worth perusing.

Jane McGonigal gives one of the better summaries on Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi's work, in her second chapter of Reality is Broken. Near the end of the chapter, she briefly summarizes neurochemicals likely at play when we're experiencing the compelling in games, from adrenalin to oxytocin. This seems a hugely underrepresented path to mapping a lot of what we really mean by "fun". I recommend McGonigal's book, if only because it's the first about games to have hit the NYT Bestseller list. Reality is Broken was a first look at design for an awful lot of non-games folk.

It'd be hard to define fun and ignore the intended delivery mechanism. To that end, Ian Bogost's Videogames are a Mess works as an outline to major debates surrounding games (his Persuasive Games being essential to defining them), and Steve Swink's bubbly Game Feel piece is worth a look (for, the least of which, the balding fat man imagery). Hunicke's MDA [pdf link] is popular, Richard Bartle's Players Who Suit MUDs is a classic read, and Nick Yee's Daedalus is in some places a great extension of Bartle, and in all other parts great original work.

Look long enough at any one of these authors, and you'll get pointed toward dozens of smart pieces on fun and games. If your goal is to contribute, then show us where you fit. Don't spray and pray vapid semantics. Arguing about fun is like bombing for peace. At least try to avoid collateral damage. Better, contextualize your ideas and join the conversation. Better still, make your own new hieroglyph. Words on a page are rarely as good an illustration of fun as, say, an actual fucking game.

The present language of fun isn't just symbolic, it's incomplete. That we use games to talk about games -- whether it's bags upon bags of person-shaped figurines and multicolor plastic tokens, all poached from older games, or a "to play" pile of Xbox shooters -- the present history of titles simply doesn't represent a full language. We're not there yet. The nature of experience is too big, our patchwork language too small.

The problem with our present set of hieroglyphs, the rubber-stamp game concepts out there, it's getting common to have the same conversation with players over and over. And where novelty -- especially if you buy into this idea that it's creating a practical, mishmash language -- meets a game that actually gets finished, that expands the possible. Enriches our ability to converse. For now, big houses can get away with the PR-approved novelty that comes from bedazzled graphics and polished, epic soundtracks. But for people who love the medium, it's no surprise the trend would raise alarms.

Historically, it doesn't always work out.

During the 18th Dynasty of Egypt (roughly 1550-1300 BC) -- known for such Pharaohs as Tutankhamen and Hatsheput -- scribes reproduced papyrus scrolls of a text ingrained into ancient Egyptian daily life: The Book of the Dead -- a version known as the Theban Recension, a collection of hieroglyph spells meant to guide a person past the trials of the afterlife.

Originally, starting from the left-hand side of the scroll and working to the right, scribes inked both the spells, and small vignettes. They used black pigments, mostly, to outline small illustrations.

Approaching the end of the 18th Dynasty, up to the 21st (around 950 BC), papyri copies of the Theban Recension are painted in reds, greens, yellows, and white, with all the text wrapped in red and yellow borders. They're beautiful; see for yourself with a quick Google. They're the work of master artists, contracted to make larger, grander vignettes, leaving less and less room for the spells.

Even with plenty of space, whole sections of "the magic" start to get left out. Sir Wallace Budge of the British Museum wrote that one 21st Dynasty scribe, "knew or cared so little about the text which he was copying that he transcribed the LXXVIIth Chapter from the wrong end, and apparently never discovered his error, although he concluded the Chapter with its title."

The Book of the Dead was old even in the First Dynasty of Egypt, with kings and peasants giving its hymns and prayers real belief. They trusted in its ability to lead them to the light of Osiris, that the scribes and priests were sincere. But the scribes couldn't keep up with the market. Copies of the Theban Recension were eventually mass produced with spelling errors, omitted words, and fill-in-the-blank spaces for the purchaser's name.

The Book of the Dead was old even in the First Dynasty of Egypt, with kings and peasants giving its hymns and prayers real belief. They trusted in its ability to lead them to the light of Osiris, that the scribes and priests were sincere. But the scribes couldn't keep up with the market. Copies of the Theban Recension were eventually mass produced with spelling errors, omitted words, and fill-in-the-blank spaces for the purchaser's name.

Our present language of fun isn't just incomplete, it's degrading into a cacophony of social gaming ripoffs and first-person déjà vu. Not just the same games, with more polygons. Or, well, sometimes that's exactly what they are. It's hard enough to speak in an incomplete language, but without pressure to experiment or innovate, "fun" is getting derivative. Fun is getting less fun.

Like the Egyptians, developers seem to have forgotten that fun's the icing, not the cake. Nothing wrong with icing. Some of what raised up great works of the last three millennia was decorative -- the arresting styles of Bram Stoker or Van Gogh; historic shifts in skill and execution brought out by Jimi Hendrix or Imhotep. It makes a difference, in the final product, but it's a mistake to confuse it with substance. In every creator just named (and, sure, it's my subjective opinion) style and substance came together.

In her well-known GDC talk on Train, Brenda Brathwaite describes hearing Mary Flanagan, another designer, refer a game as "my work". That the subtle change of language brought on a weird transformative moment, helping to further shift how she thought about the medium. Not long after, at Ian Bogost's tenure party, she's having the standard games industry conversation, "So what are ya workin' on?" "Can't say." "Yeah, me neither." But, this time, Brenda was working on some board games because she wanted to, because she could. Trying to use games to capture the difficult emotions open to other mediums. Trying to see if that's possible.

"So, what are your games about?"

She'd made one about the Middle Passage, called The New World. One about the Cromwellian Invasion of Ireland. And just then she was working on one called Train, about The Holocaust.

"But, Brenda," says this industry person, "That's not fun."

Was Schindler's List fun? Is fun what makes blues music compelling? Brenda started to question whether fun had anything to do with meaning. That of works most likely to move us, and stay with us, some (if not most) deal with human pain. With suffering. And that under the worst atrocities in humankind, Brathwaite says we can always find a system. And with a system, designers can make a game. If we care to treat games as emotionally complex experiences, as mediums for big, moving ideas, that we need to look past the fixation with pleasantries. With just a game's ability to entertain.

It'd be a mistake to see fun and meaning as mutually exclusive. Style can help great ideas stand out. Yet, up till now the stylistic ordinance of games originated at the simple delight of them. Gamers frolicked in dreams, in ways not possible a generation ago. Of course these worlds would catch the eye. When The Great Train Robbery's highwayman pointed his revolver at the audience and fired, at the turn of the 20th century, some members of the audience literally ducked. We don't do that anymore. Novelty eats itself.

Moving from hieroglyphs to a specific alphabet should give some fresh light to fun, maybe even directions beyond it. Empowering meaning, while translating powerful aspects of the human experience into games. A refined language might provide new ways to discuss life, in the ways only games can show it. A refined language will also take context, listening skills, and time.

For now, illumination comes from action. From finishing a novel project well. With so much of concepting communicated in the language of completed games, maybe it's okay to want fewer soapboxes and more playable experience. Fun is boring when it's nested in semantics. But a thousand tangible, playable visions mixing fun and meaning? A whole night's sky, lit by a hundred constellations of play?

Speak to me, you theorists, in the sexy language of games.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like