Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Prominent Flash game designer (and current Armor games CEO) John Cooney on creating The Elephant Collection for Steam and the importance of preserving titles from a particularly creative era.

December 31, 2020 marked the day in which Adobe officially ceased support of Flash Player. Starting January 21, 2021, the company blocked Flash content from running with the plugin. This, of course, shuttered hundreds of thousands of games and animations that people had been making for over two decades. Many studios you know of nowadays, such as The Behemoth (Alien Hominid, Castle Crashers) and Cellar Door Games (Rogue Legacy), got their start in Flash.

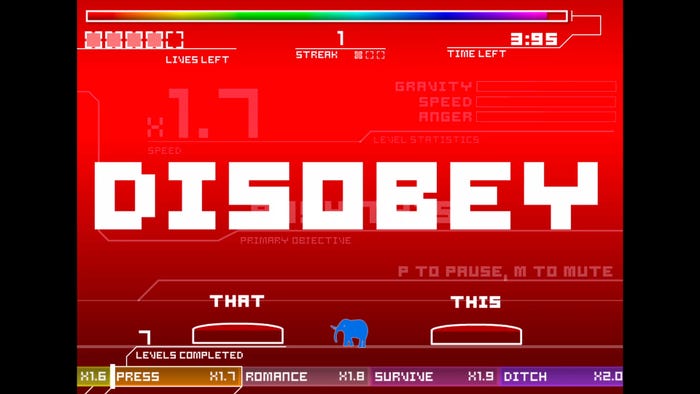

One prominent developer and current CEO of Armor Games, John Cooney, built a notorious presence around his work thanks to projects like This is the Only Level and Achievement Unlocked. After lending a hand making The Scriptwelder Collection happen alongside Armor Games Studios, which bundles the Deep Sleep and Don't Escape games from Flash developer scriptwelder for Steam, Cooney is giving the same treatment to some of the games in his portfolio with The Elephant Collection.

The idea for The Elephant Collection came to mind five years ago. As Cooney tells Game Developer over Zoom, he thought it would be a good way of preserving some of his games (a total of ten) by bringing them over to Steam in one package. Not just to present a modernized time capsule of his work in Flash to new audiences, but to share them with people who, up to this day, are still sending him text support emails about these games, and asking if they will ever receive a port.

"Alongside all the work that went into thinking what does this look [like]," he says, "[such as] how many games should be there, which games are important, should we do all of them or only some of them, life caught up in a lot of ways. I ended up having two children, there was the pandemic, and I shifted roles from Kongregate to Armor Games. And so there were a lot of things going on in my life, and meanwhile, this project was slowly moving forward a little bit at a time."

Ultimately, the decision to work alongside Armor Games just made sense. Cooney originally joined Armor Games back in 2007, where he stayed up until 2012. He then had a seven-year tenure at Kongregate, until he rejoined Armor Games in 2019 as vice president of business development of Armor Games Studios, and became CEO two years later. Given how intertwined the company has been with his career, he says, it felt natural that they'd be moving forward as a publishing relationship.

There were a few key factors that Cooney and the team wanted to preserve, especially when attempting to provide a modern experience for these Flash games. Some of his earlier games had a resolution of 550x400 pixels, for example, with one being pretty much the same size as a postage stamp at 250x200 pixels. For The Elephant Collection, they're currently targeting around three times the original size of every individual game.

"We've put a lot of thought and care into figuring out how to pretty much upscale and clean up and remaster a lot of the art in these games," he says. "Thanks to Flash being Vector art, it's a lot of art that is drawn in geometry. It's why Flash games were so small back in the day. Instead of transmitting every pixel individually and having these huge file sizes, Flash files would just send instructions like, draw a rectangle from here to here, and that's why games were like 2 MB or something like that. We used to email Flash games to each other."

While the process of scaling elements has proved to be far more amenable than originally thought, the team has encountered a few unforeseen challenges. Thanks to those early low resolutions, some of the games that featured flashing effects weren't as much of an issue for folks who are triggered by flashing lights or who might be prone to seizures. But things are different when games aren't displayed at 250x200 pixels. So there have been considerations around epilepsy.

There's also a particular consideration of what made Flash games so particular. In Achievement Unlocked 2, there's a point at which the objectives list teases you into opening a second game on a second window. "We built a connector that actually chatted with the other window," Cooney explains, "and so they would communicate what was happening in the second window with the first window, so you're actually playing in two screens at the same point. And we had to figure out how to do that. Because, again, the Steam PC experience is, you open up a window and you play a game, there isn't a notion of you opening up a Steam game, and then you open a second Steam game. So we had to come up with workarounds for that to make it still [capture] that experience."

Aside from these tweaks to the games themselves, as well as a hub world of sorts that you can walk through, connecting the games—which Cooney calls "experiences within an experience"—he realized early on how important it was to preserve what made his games stand out in the first place. More often than not, surprisingly, it's the bugs and small issues that never got patched out that are the most important to keep. The speedrunning scene around This is the Only Level, for example, is still wildly active.

"[The games] are fully playable but there are little exploits and things that are important to preserve, too. People want to be able to do what they effectively felt was a cheat code 12 years ago, and do it again and feel the impact of that nostalgia. That knowledge that people for some reason put on a shelf in their brain and wanted to put back out at some point," Cooney says.

Before social media cemented itself as the primary channel of communication, the community of indie developers around Flash, as well as the players themselves, gathered in places like Newgrounds and Kongregate, talking to each other in comment sections and reaching out to creators to chat about their work.

Due to the nature of the web back then, there were many quirky occurrences. Bugs (like the ones in This is the Only Level ) had the potential of being considered a feature—a long-running joke in the community across Flash games as a whole. One of Cooney's games, called TBA, is named as it is since fans began sharing the news of his new project without actually knowing what TBA stands for: To Be Announced. "It got to a point where I realized I had kinda broken a marketing rule or something by not actually announcing the game of the name correctly," he says. "And I ended up releasing the game called TBA. It was one of the funny anecdotes of the Flash games days."

Cooney remembers getting messages on AOL and Messenger from players directly, oftentimes saying that they had enjoyed his games and were wondering when the next one would come out. During a GDC talk about Flash games, he also mentioned that people would warn him and other creators whenever a portal had stolen one of their games and published it as their own, which was a problem that only became more pervasive over time.

Games during this web 2.0 period, despite the lack of YouTube, Twitter, and everything else we know of nowadays, still had the potential to be huge hits. Cooney remembers how people would sometimes launch games on a portal like Newgrounds or Armor Games, and within 24 hours they would be at over a million plays already. All the way from Kongregate to the Neopets boards, as well as the array of forums, led to dozens of communities flourishing online. In the case of Flash games, it was a direct line, and a time Cooney has serious nostalgia for.

"Flash was magic," he says. "These Flash games were tiny. You'd have a pretty robust fun gameplay experience, and it was magic because of the fact that, so many developers including myself got our start in Flash games. Our first distribution platform was the web. Newgrounds, Kongregate, Armor Games. For a lot of us making these games was a hobby. Putting things together and then just sending them out into the sea and hoping it does something. It enabled so much creativity and freedom of just building really cool little experiences in these little packages."

The simplicity of the onboarding experience, as well as the familiarity to those who knew the basics of tools like Paint, made Flash so welcoming for many, including Cooney himself. He recalls how easy it was to just build a rectangle, add text, use a paintbrush, and then start creating on the canvas. This would eventually lead to a button, which then resulted in a slideshow where you moved between multiple canvases, and all of a sudden you found out that you could attach different scripts to that first button. So on and so forth.

"It put you into the shallow end of the pool and then allowed you to swim towards the deep end at your own rate," he says. "It was so easy. If it was intentionally made as easy as it was to make games, those developers were absolutely incredible. I'd never call myself a great programmer, but as someone who didn't know any programming going into Flash, Flash taught me how to program. I learned little by little how to make games."

To Cooney, there are quite a few reasons why remasters and remakes have become such a common occurrence in the past few years. On one end, he sees it as a demand from people to play a game that was important to them at some point in their lives. "The games we play are memories, they're important milestones in our lives," he says. "They're things that are not just connected to us as players, but they're also tied to the environment that we were at the time. A lot of media does this, but games kind of do it in a special way."

He also sees preservation as important from the perspective of developers and publishers. On his end, he's been adamant about finding a way to make his games work again. He sometimes goes to the website where his first Flash animation is still hosted and running to this day, just to remember the time in which he built it during high school, using one of the computers there. Once Adobe announced they were going to sunset Flash, it became important for Cooney to be able to go back, not just as a developer and share what he made with others, but so he can go back on a personal level and witness how far he's come, and how important his work eventually became.

"Preservation efforts for games are critical to our industry," he says. "It's important that we have ways to preserve the content that's created, and my concern is kinda what happened to the film industry. So many early films and so many things have been lost because there wasn't an effort to find ways to store and preserve them. And in the same way, I feel that games need more champions to preserve content and to make sure that future generations can enjoy it. Not just for the creators who create, and to have their work visibly and playable and seen, but to also capture history in a way."

Regarding the Flash scene in particular, there have been multiple efforts to preserve part of the games and continue having them playable for the foreseeable future. Cooney mentions an emulator to play Apple II games in the Internet Archive, as well as Ruffle, a Flash emulator that acts as a web plugin just like its homage. Yet, he recognizes that preserving these games is a task that comes with volume. Kongregate alone has over 100,000 titles, and the numbers grow exponentially larger for Newgrounds when you group up games alongside animations.

"Preservation efforts for games are critical to our industry,"

At the end of the day, it depends on what the developer is looking for in terms of its preservation goals. If its merely for the purpose of preserving and distributing games, options like Ruffle or using tools like Adobe Air to port them to Windows, Mac, and mobile devices are great ways to do so. When it comes to launching games on Steam, for example, it's important to consider how the platform functions and think about the player expectations therein. Some Flash games were 15-second experiences, or encompassed rounds that could be repeated in the span of a few minutes before moving to something else.

"There are different player expectations on different platforms for what is worth their time and value and money for," he says. "Because you will be launching your game to whatever giant AAA is out on Steam, and that's kind of the beauty of Steam, small indie games launching alongside AAA games. But, also, Flash games look very different, they look very 2000s in a lot of ways, so it's important to also think about how these games are gonna look and what players are looking for."

Cooney hopes that, at some point in the future, there will be a tool similar to Flash—one that is available to everyone, and has a welcoming onboarding process to people who are just starting to make games. At the same time, he recognizes that there is a lot of software available nowadays that is either completely free or free to access, and doesn't present itself as daunting as Unreal Engine or Unity to people who're just starting out. GameMaker, Godot, Construct, and Scratch are some of them. This, too, is important to preserve for future generations.

"It really does help when you're getting into games to have something that is more of an incremental step, taking things that you already know from how you use a computer," he says, going back to the example of Flash being similar to Paint. "Having that intermediate stuff was, at least for me, critical as a developer. Getting the basics done before jumping into Unity, which opens up with this 3D canvas with all these buttons and terms and things that take time to learn what they mean and how they function. There are more tools now than there ever have been, and more are free and approachable, which is great compared to when I was in high school and getting into games. I think there's a lot of good opportunities, and these tools are only getting better."

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like